This is the real reason why the eurozone is suffering from labour shortages

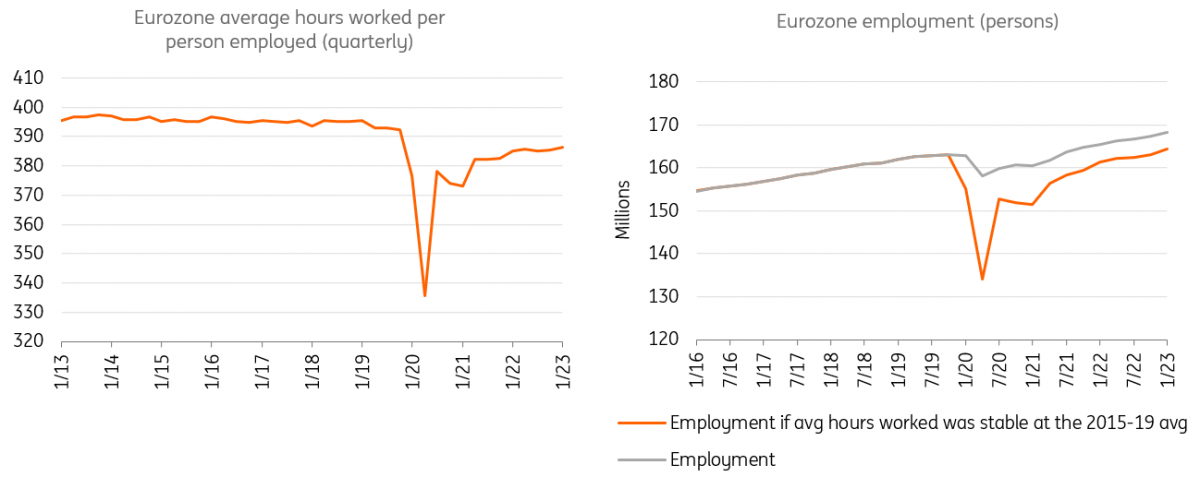

The drop in average hours worked in the eurozone is one of the biggest and somewhat overlooked shocks caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. We think this is the main reason for current labour shortages. This drives down potential output and causes inflationary pressure, which begs the question: can this trend be reversed?

Eurozone labour market: at a glance

- Average hours worked per employed person are still 2.2% lower than they were in the pre-pandemic years. This has a very large impact on the labour market.

- We argue that labour shortages are in large part not cyclical or ageing-related, but mostly stem from lower average hours worked per person employed.

- Because of this, 3.8 million people are now in work which would not have been necessary if people worked the same hours they did in the years before the pandemic, and the eurozone would likely not experience meaningful wage pressures.

- This trend in lower average hours worked is observed in most sectors and for both men and women and across all age groups.

- It is hard to fully account for the reasons, but increased sick leave, labour hoarding and some compositional effects, such as the increased entry of women and younger workers into the labour market, seem to be playing a role.

- If there is a rise in the average hours worked, this could mean that labour shortages ease and wage pressures moderate more quickly than expected.

- If average hours worked remain as they are, this lowers growth potential and makes labour shortages and wage pressures more structural.

- Policymakers would benefit from a better understanding of this phenomenon as any further developments in the average hours worked trend will have significant implications for monetary policy, unemployment and economic activity moving forward.

Labour shortages are mainly being driven by lower average hours worked

Despite the fact that the eurozone economy has broadly stagnated, job creation remains strong and the eurozone labour market seems to be tighter than ever. The good news is that the unemployment rate has fallen to a historic low of 6.4% on the back of this. At the same time, eurozone enterprises now see labour as the largest supply-side problem hindering their business, and the ECB worries that the tight labour market will keep inflation above target for longer. Clearly, the labour market is one of the most important parts of the economy to watch at the moment.

Strong economic recovery and ageing populations are often cited as the key reasons for labour shortages. What is often overlooked is the lower number of average hours worked per person that has occurred since the pandemic. While the ECB has previously written about it and President Christine Lagarde mentioned it in her Jackson Hole speech, the extent of the impact of this is very large.

The average number of hours worked per person was fairly stable between 2013 and 2019. It experienced a large drop during the pandemic – which was mainly caused by the massive take-up of furlough schemes – but has never fully recovered since. While the recovery is still ongoing, the trend has slowed substantially. This means that more people are needed to do a similar amount of work. At the moment, this equates to 3.8 million more people employed than if everyone was working the average amount of hours they did in the years before the pandemic.

The gap in average hours worked amounts to 3.8 million more people in work

This excess of 3.8 million workers equates to about two percentage points of unemployment, adding to a substantial easing of labour shortages. Of course, a lot of people would not have been looking for work in an environment that was not this exceptionally tight, however even using the Abel and Bernanke (2005) Okun’s Law estimate, we find that recent GDP growth should roughly correlate with an unemployment rate of 7.5%. This is by no means high, but it is high enough to not generate meaningful wage pressures, according to the European Commission’s natural unemployment rate estimate.

So, the argument that the current economy is so strong that it causes labour shortages does not really hold up, especially given the fact that total hours worked have only just breached pre-pandemic levels. Ageing populations – which are expected to cause the active population to shrink over time – are also not a reason for current shortages, as the number of people at work and looking for work has never been higher than it is now. The main cause for shortages seems to lie in lower average hours worked.

An Okun’s law estimate would currently put eurozone unemployment at 7.5%

The reasons for the drop in average hours worked are not clear cut

It is tough to get a full picture of what’s causing the average hours worked per person to remain so low. Oddly, the number of people working part-time has decreased since the start of the pandemic, which actually has a positive effect on average hours worked. When looking at the average number of hours worked by part-timers, these are even increasing at the moment. On the other hand, the number of hours worked by full-timers has come down.

Part-time work has dropped significantly since the start of the pandemic

Sick leave and labour hoarding are plausible reasons for the drop in average hours worked, as the ECB also concluded in a recent blog post. Sick leave was up significantly in 2022 for countries providing data, such as Germany, the Netherlands and Spain, but it is hard to match the numbers to the loss of hours worked. This seems to be in part related to "long-Covid", but other types of longer-term sick leave also seem to be up, according to anecdotal evidence.

Labour hoarding could also contribute to the lower average hours worked. In these times of shortages, businesses could be holding onto employees they might need in the future by making them work fewer hours. The ECB reports that “firms have been reluctant to let go of skilled employees who would be needed in the future”.

What could also be happening is that the people who have been hired since the pandemic want to work fewer hours, bringing the average hours worked down. In a tight labour market, this could happen as people are able to make more demands in negotiations with employers. There is no data to provide evidence on this though.

There is also a compositional effect at play, but that does not fully explain the fall in average hours worked. Still, the reduction is influenced to a degree by the demographics of those in work and in what sectors. Female full-time workers work fewer average hours per week than men and women have been entering the workforce more in recent years. Female employment (at 32 average hours per week) has grown by 4% since the fourth quarter of 2019, while male employment (at almost 38 hours per week) grew by just 0.8% over the same period. While this contributes to the average decline, there has also been a sharp fall for both men and women in average hours worked, indicating that the compositional effect does not explain the full story.

The same can be said when looking at the sector breakdown. More people have found employment in sectors with lower average hours worked, but the impact of that is marginal to the overall outcome. If we held the shares of employment from 2019 steady throughout the pandemic, this would not have resulted in a different employment outcome. We do note that hours worked fell more for the sectors that saw employment grow quicker, but we would be cautious in calling that a compositional explanation for the decline in average hours worked. It seems more logical that the stronger drop in average hours worked resulted in more demand for workers to keep output up. Indeed, labour shortages are largest in sectors that saw average hours worked fall most.

So overall, it is hard to fully pinpoint the causes of why average hours worked per person are now so much lower than they were prior to the pandemic. A variety of reasons like sick leave, labour hoarding, and the composition of the labour market will play a role. That means that both the demand and supply side of the labour market influence this. But we could of course also miss contributing factors.

Vacancy rates are highest in the sectors with the largest drop in average hours worked

Two different outcomes are possible, both with significant implications

Since we don’t fully understand the workings of this, it’s hard to say what comes next. But both a recovery to the previous level of average hours worked per person and a stabilisation at the current level have serious implications for the eurozone economy, businesses and the European Central Bank.

If it turns out that the recovery in average hours worked per person regains speed, the coming years will probably see easing labour shortages, but also higher trending unemployment as fewer people will be needed to reach the same hours worked. This would relieve wage pressures substantially. In turn, this would dampen overall household income and consumption, but it would not necessarily be triggered by any regular cyclical development. It means that the labour market would become less tight without a macroeconomic event causing it.

If a recovery in average hours worked were to happen, it is very likely that most forecasters are underestimating this as it is something that models do not pick up on. That makes it likely that the ECB staff's macro projections – currently expecting a further drop in unemployment over the coming years – do not take these possible developments into account.

If the average hours worked per person do not recover meaningfully from here, this means that there has been a permanent shift lower in total labour supply. This results in more permanent labour shortages and quicker wage pressures – like we are already seeing now – and therefore means that monetary policy should remain tighter compared to a situation where average hours worked are higher. Overall, the average output per worker being reduced means that potential output will be driven down at a time when demographic forces will start shrinking the labour force. A prospect that lowers GDP growth expectations for the medium term.

Both possible outcomes will have profound implications for understanding the post-pandemic eurozone economy. It is therefore imperative that we gain a better understanding of what drives the downturn in average hours worked per person more precisely.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article