The new decade: Weak eurozone growth with a simmering existential threat

Even before the coronavirus outbreak, dark clouds had been gathering over the eurozone economy, with Italy in the eye of the storm. Over the next 10 years, the region's potential growth rate will likely slow to a crawl while Italy faces a stagnation far worse than anything Japan has seen

Growth below 1%

As a new decade dawns, expectations for growth in the eurozone are meagre at best. The outbreak of the coronavirus has already derailed a fragile economic recovery this year and is threatening to push some countries into recession.

But the region's economic challenges aren't confined to the short-term. In the next 10 years, demographic and structural headwinds, and a limited appetite for reform, could push the bloc's potential growth rate to less than 1%, down from the annual average pace of 1.4% of the previous decade.

Slowing growth in mature economies with high GDP per capita levels is a relatively new phenomenon in modern economic history, which is why the eurozone is often compared to Japan- a country which has long struggled with low growth and low inflation and is also confronted with an ageing population and shrinking workforce. We have already written about the eurozone’s possible 'Japanification' here and here, arguing that this is not the worst possible outcome given Japan's high living standards and GDP per capita levels.

Much more troubling is the stagnation scenario playing out in Italy. Structural growth here has slowed down over the last two decades, with GDP per capita growth stagnating since the financial crisis. Despite the common belief that Japan has been the worst performing G7 economy, an average GDP growth rate of 1.4% over the last two decades is much better than Italy’s 0.5% during the same period.

Comparing Italy and Japan

There are many differences between the Japanese and the Italian economies but what they do have in common is a shrinking working age population (click here for more on an ageing population in the eurozone in the 2020s). In Italy, the working age population grew until 2013 and is now just below the level of 2000. In Japan, the shrinking working age population was even more pronounced, as it was 13.1% lower in 2018 than in 2000.

As a result of low growth in both economies, total debt has increased significantly. Taking all sectors of the economy together, total debt has increased by 61.1% of GDP in Italy and 75.8% of GDP in Japan since 2000. While in Italy, household and corporate debt increased significantly in the first years after the start of European Monetary Union, probably due to the convergence play, Japan saw a sharp increase in government debt. After the financial crisis, both countries experienced a gradual debt reduction in the household and corporate sector, while government debt surged.

One unanswered question is what a persistent, low growth environment could mean politically. In this regard, Japan and Italy are almost at the extreme ends of the range. In Japan, the stability of the LDP party since the war is an indicator of a population that is at ease with itself. The LDP party has only been in opposition twice since the 1958 elections. Italy, on the other hand, has seen some 70 different governments since 1945.

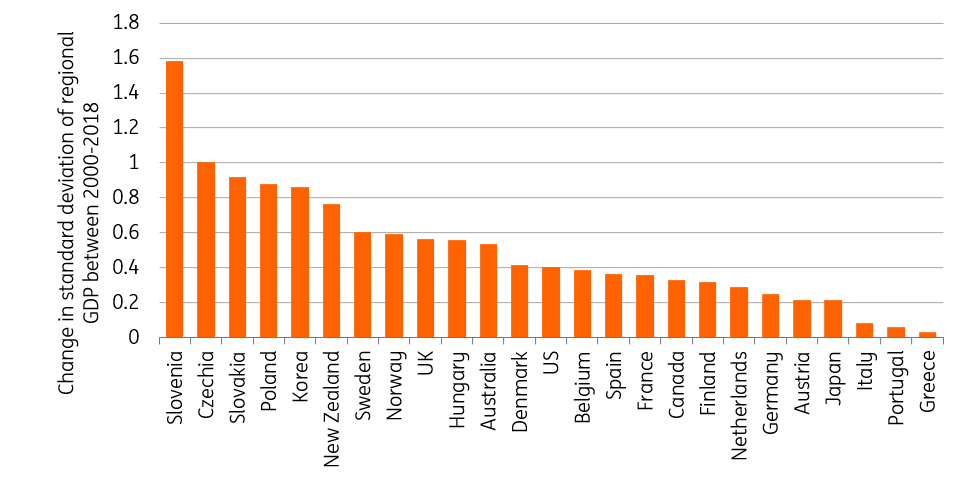

Political divides within countries are often explained away by regional inequality, with the rise of populist parties frequently linked to voters in left-behind areas. Interestingly, for countries with aggregate weak growth rates over the past 20 years, the regional differences have not grown. The differences between regions seem to grow only when countries experience strong growth rather than when growth slows to a marginal pace, as can be seen below.

Fig 3 - Regional differences do not increase in times of stagnation

Another factor that has distinguished Italy from Japan until now has been its policy on migration. Italy has retained policies of relatively open borders, while Japan has kept its borders relatively closed (although Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has also eased immigration standards). While this has worsened the blow of the population decline, immigration is less of a political divider in Japan than it is in Italy and other large advanced economies.

A further key difference is that Italy is a member of the European Monetary Union, which makes it difficult for the country to monetise debt as Japan has done. This is an important lesson for the eurozone as a whole. The Stability and Growth Pact binds eurozone member states to a fiscal conservatism that rules out increasing government debt to keep growth levels higher.

Lessons for the eurozone

Italy’s experience with low growth in the last two decades is clearly worse than Japan’s experience. Obviously, there are many different reasons for this but a couple of observations catch the eye: Italy has had much higher growth in R&D spending than Japan – by a whopping 86% compared to 11% over the course of 2000 to 2016 - but annual growth in Total Factor Productivity (TFP) was much weaker in Italy than in Japan - a rather counterintuitive outcome.

This is partly a result of the lower base from which R&D started to grow, but it also relates to Italy’s productivity problem, which is considered an important reason behind Italy’s poor economic performance. Explanations for low productivity growth in Italy include resource misallocation, the large amount of very small businesses that generally struggle with growth, product market rigidities, a lack of investment in ICT, education and most recently a lacking of managerial skills. That is quite a list of issues that may be holding back the Italian economy from growing faster even in times of a declining working age population.

Another factor holding back productivity growth is deteriorating government effectiveness and the rule of law. These have diverged between Japan and Italy and could be an important driver of the different economic performances despite similar policy efforts. Gros (2011) argues that the deterioration of the Italian institutional framework as documented by the World Bank – see figure 4 – is one of the more important factors to consider when looking at Italy’s economic underperformance since the early 2000s. In Japan, this has not been the case and the World Bank has even reported improvements in its institutional structure, suggesting that Italy's declining institutional framework has indeed had a substantial impact on its falling GDP per capita.

The differences between Italy’s and Japan’s experiences with low growth are large and provide important lessons for eurozone policy makers. Technological progress, the rule of law and government efficiency are key in determining whether a low growth environment is a blessing or a curse.

Without the ability to monetise debt, improvements in the potential growth trend should mostly come from structural reforms. But when both of these adjustment mechanisms are absent, income per capita is at risk of contracting for a longer period of time, as the Italian case illustrates. As the eurozone reform agenda is not very ambitious right now, growth divergence is set to continue, which only makes the European Central Bank’s job harder and continues to be a simmering existential threat to the monetary union.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

3 March 2020

The new decade in Europe This bundle contains 6 Articles