Tense times in world trade

The threat of new trade wars is smaller, but tension hasn’t let up between the US, EU and China. Exporters continue to face higher costs and uncertainty that could weigh on trade growth after this year’s boost from economies opening up

No respite from trade tensions

The election of President Biden was never expected to turn the clock back to before the trade war but did offer the possibility of a less adversarial, and perhaps less active, US trade policy. But things haven’t quite played out that way. A bad-tempered exchange between US and China officials at a summit in Alaska in March has been followed by more Chinese firms being added to the US Department of Commerce’s ‘entity list’, banning them from exporting to the US.

With little change in the US stance towards China, the trade war tariffs on China and US imports look likely to remain in place. Katherine Tai, confirmed as the US Trade Representative in March, is conducting a review of US trade policy towards China, including the trade war tariffs. But the tariffs are unlikely to be scaled back significantly until the US is satisfied that progress has been made on China’s treatment of foreign intellectual property, which Tai has suggested will require other legal tools.

Tensions have risen between the EU and China, too. In March, the EU used a newly adopted regulation to impose sanctions on Chinese officials and entities, including asset freezes and travel bans (the US, UK and Canada also imposed sanctions). China has retaliated with its own sanctions on individual EU politicians, officials and academics. As a result, the investment deal negotiated between EU and Chinese officials in 2020 has stopped progressing towards ratification.

We’re about to find out if EU-US trade relations have turned a corner.

We’re about to find out if EU-US trade relations have turned a corner. The threat of US tariff increases on EU carmakers ended with the Trump presidency, but US tariffs on steel and aluminium products remain a source of tension with the EU, and the US is facing imminent increases in tariffs on its exports to the EU (when the US imposed the tariffs in 2018, the EU delayed part of its retaliation. In June 2021, time will be up).

In March, the US and EU suspended tariffs in their other major trade dispute, about subsidies to Boeing and Airbus, and this could still happen in the case of the steel and aluminium tariffs. The two sides agree the root cause of problems in steel and aluminium competitiveness is overcapacity in China. Simply agreeing on this is probably not enough to persuade the US to give up on its Section 232 tariffs – certainly not for all its trade partners – but if the EU and US can agree on actions to take, there is a chance of avoiding the EU’s increase, and perhaps seeing all US and EU tariffs in this dispute rolled back.

US tariff increases in 2018-19, and retaliation by its trade partners, have been followed in the pandemic by many countries raising trade barriers. Along with tariffs, other less visible trade barriers in the form of subsidies and export bans on specific products have also been creeping up (Chart 1).

Chart 1: New policies are mostly harming trade

Global total numbers of new policy measures affecting trade, 2009-2021

Reshoring and technology competition

At the start of the year, the EU and US both announced initiatives to increase their supply chain “resilience”. Although reshoring isn’t mentioned directly by either the EU or the US, the initiatives carry an implication that foreign suppliers are a source of risk, which some domestic production could help to offset.

In the EU’s case, specific attention is given to the health sector, with possible policy solutions already sketched out (crisis preparedness, diversifying production and supply chains, stockpiling, and fostering production and investment – not necessarily in the EU). In parallel, within a new digital strategy the EU set a target of doubling its share of global semiconductor production to 20% by 2030.

For the US, shortages of medical goods at the beginning of the pandemic are used as a jumping off point for a review of supply chains in several sectors, including critical minerals, semiconductors, and electric vehicle batteries, to report in June. A further set of sectors, including defence, energy and food production will also be reviewed over a longer timescale. In parallel, the US has announced Buy American, strengthening the obligations on Federal agencies to buy from domestic producers. Versions of the policy have existed for decades, but never in combination with such large-scale fiscal stimulus.

China had already been steadily reducing its dependence on foreign suppliers before the pandemic, with Chinese firms handling an increasing number of the steps in manufacturing, from simple to complex processes. China’s new five-year plan, announced in March during the Two Sessions, focuses on further self-reliance in the manufacture of increasingly advanced technology.

In the near term, not much will change while EU and US policymakers build up a picture of their selected supply chains, and China continues down its path of upgrading its manufacturing capability. Reshoring won’t happen while firms face higher costs to source from home, so competitiveness needs to be improved, through investment, but also reducing ‘red tape’, and access to suppliers, skilled labour and markets.

Even as the relative costs of complex, globalised supply chains increase – if tariffs remain high, or rise further, and if domestic competitiveness improves - the recent past suggests that production is slow to shift back home. The trade war shocks to the US-China trade relationship, in terms of the higher tariffs as well as ongoing uncertainty, have seen changes in the main exporters to the US, but little reshoring.

A growth threat

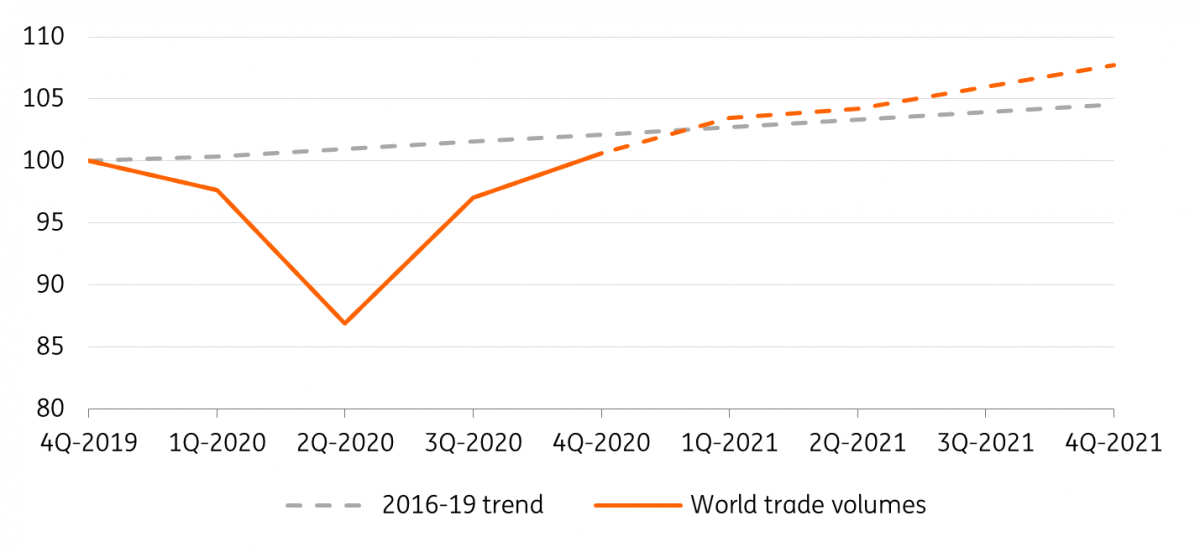

Trade will still receive a boost this year in spite of higher costs and barriers in the background, as economies open up and congestion eases (Chart 2). Even though it is services still mostly affected by lockdowns, there are imported goods involved in say, hospitality. And travel restrictions easing will allow air cargo volumes to increase, relieving some pressure on ocean freight. More generally, the congestion in ports and availability of empty containers is expected to improve.

But in the longer term, the reality of new trade barriers may mean trade is unable to improve on its relatively weak growth in 2016-19 when uncertainty and costs increased markedly.

Chart 2: world trade will still grow strongly in 2021

World trade volumes, 2020-2021

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article