Swedish elections: Winner takes nothing

A very tight vote leads to a deadlocked parliament. Lengthy negotiations likely lie ahead, with little prospect of a strong government. The economy (and the krona) will probably remain in no man’s land

A dead heat

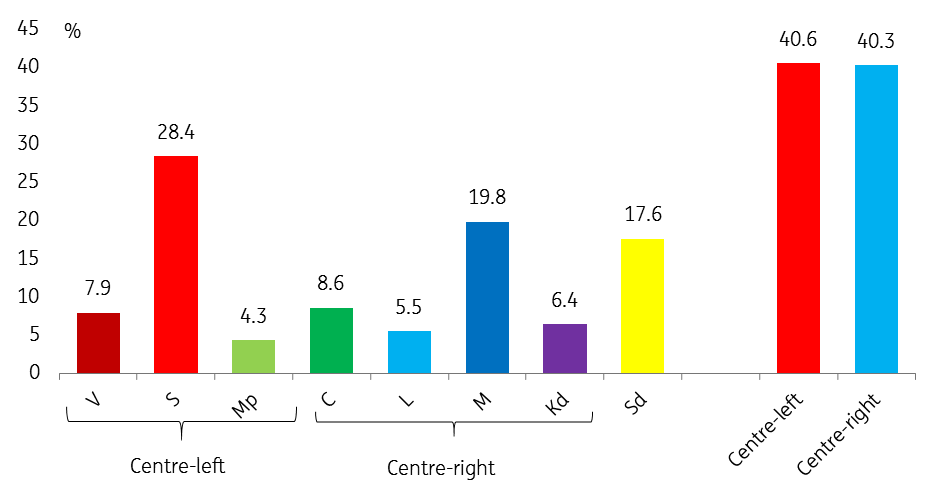

The Swedish election result could hardly have been closer. On current projections, two major political blocks are separated by a single parliamentary seat (144 vs 143). The margins are so close that votes from Swedes living abroad, which will be counted by Wednesday, could shift the outcome (based on previous results, the centre-right are likely to gain a little).

But the rise of the far-right Sweden Democrats means that neither the current centre-left government nor the centre-right ‘Alliance’ is anywhere near a majority in parliament.

The two centrist parties are in the (potentially unenviable) position of kingmakers. If they were to accept either a centre-right government or a Social Democrat government supported by the Greens and the Left, that would end the impasse

Going by the statements each party made ahead of the election, there is no feasible majority based on the current parliamentary arithmetic, which means compromises will be necessary. Negotiations have already started, but it will take some time for the parties to work out where they stand.

Relative to the previous election, the extremes have gained: the Sweden Democrats have increased support from 12.9% to 17.6% and the Left from 5.7% to 7.9%. The government parties lost support, in particular, the Greens (down from 6.7% to 4.3%). The alliance parties have seen votes redistributed from the Conservatives to the Centre and Christian Democrats, but have gained little overall.

Preliminary result

What happens now?

Prime Minister Stefan Lofven has announced he will stay in office and seek renewed support for a government led by the Social Democrats. The opposition parties have called on him to resign, and want to form a centre-right government. So, ahead of what looks likely to be long and tough negotiations, this will amount to little more than political theatre.

In reality, the parliamentary situation is exceptionally complicated. Neither of the traditional political blocks can form a government without consent from either the other side or from the Swedish Democrats. Even combinations such as a centrist government (S+Mp+C+L) or a right-wing government (M+Kd+Sd) are short of 50 %, which means some cross-block solution is necessary.

Arguably, the two centrist parties (C and L) are in the (potentially unenviable) position of kingmakers. If they were to accept either a centre-right government supported by the Sweden Democrats or a Social Democrat government supported by the Greens and the Left, that would end the impasse.

However, both of those options go against their election manifestos and would risk them losing support in future elections. The centrists have said they would prefer a centre-right government, but if that proves impossible, they are open to a deal among the mainstream parties (aimed at excluding the Sweden Democrats and the Left from influence).

In the medium term, the worry is that another weak government means another four years without meaningful economic reforms, and if Sweden suffers an economic downturn or financial turbulence a minority government could prove unable to take decisive action

Indeed, they may spot an opportunity in that if both the Social Democrats and the Conservatives refuse to accept a government led by the other, a possible compromise could be for the two largest parties to step aside and support a centrist minority government. There is some precedent for such a solution, though previous centrist governments in the 70s and early 80s proved unstable and short-lived.

Whatever compromise the mainstream parties work out, the new government is likely to struggle with either a weak parliamentary position or internal divisions. It is hard to see a constellation that will last long once it starts governing. And a government forced into constant compromises could prove a poisoned chalice for the parties involved, accelerating the draining of voter support from the mainstream towards the Sweden Democrats and the Left. New elections (the first since 1958) could prove the only way out of what looks like a political cul-de-sac.

Key dates

12 September: All votes counted and the final result confirmed

24 September: New parliament is seated, and elections for a new speaker and deputy speaker take place. If the current government doesn't voluntarily step down, a vote of confidence must take place within 14 days.

15 November: Final deadline for a new government to pass a budget for 2019. If no budget is passed current spending plans are likely rolled forward.

25 December: Earliest date that a new election can be called. The new vote would most likely take place in mid-March next year.

What does all this mean for the economy?

The political stalemate has limited near-term implications for the Swedish economy. With a stable institutional framework, Sweden can probably operate on auto-pilot for some time. There is no obvious need to change the budget for next year, nor does the government face genuinely urgent economic decisions.

In the medium term, the worry is that another weak government means another four years without meaningful economic reforms and that if Sweden suffers an economic downturn or financial turbulence, a minority government might be unable to take decisive action.

Having said that, Sweden has a long tradition of the mainstream parties acting together on both long-term issues (e.g. pensions and defence) and in crisis situations (in 2008 and the early 90s crisis). A key question in the months ahead is to what extent the acrimonious election campaign (and the potentially fraught aftermath) has eroded the capacity for such consensus solutions.

And the krona?

With EUR/SEK already down from 10.70 to 10.45, it looks like most of the ‘it could have been worse’ relief rally is probably in the past. The krona is in limbo until there is more clarity on what happens next on the political front. If the parliamentary deadlock cannot be broken and new elections are announced some of the political risk premium seen in the run-up to the vote could easily return.

Until there is new information on the political front, attention will start to shift back to the economy and central bank outlook. The immediate focus is on inflation data this Friday and the Riksbank minutes next Monday. We continue to see the underlying story as SEK negative: the domestic economy is slowing, the Riksbank remains among the most dovish central banks, and Sweden is highly exposed to the impact on global trade of the Trump administration’s aggressive tariff policies.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

10 September 2018

In case you missed it: The surprising and predictable This bundle contains 9 Articles