Supply strains hold back the US jobs market

US jobs growth disappointed again in May, but this is not a demand issue. A host of reasons are keeping the supply of workers constrained, which means firms are having to pay-up if they want to recruit staff. Tensions will eventually ease, but in the near term it heightens the risk of more elevated inflation readings

| 559,000 |

The number of US jobs added in May |

Jobs miss again as firms struggle to find workers

So, US payrolls growth has disappointed again in May with a net 559,000 jobs created versus expectations of 675,000. The range of expectations was wide at 335,000 to 1 million, but we had suspected it would come in on the softer side due to a lack of labour supply rather than any drop-off in the demand for workers.

There was a net 27,000 upward revision to the past couple of months of data while the details show private payrolls rose 492,000 versus expectations of 610,000. For the second consecutive month we see a drop in construction employment, which seems odd given the strength in activity in the sector. Meanwhile retail fell 6,000, financial services fell 1,000 and Federal government employment fell 11,000. Leisure and hospitality was the big growth driver with employment up 292,000 as the service sector continues to re-open and expand.

While the lost jobs continue to be clawed back in aggregate there are still 7.63mn fewer people in work than before the pandemic started. Federal Reserve officials will likely use this to justify their dovish message on eventual interest rate rises. That said, we don’t think this means the Fed is right to say there is no need to raise interest rates until 2024.

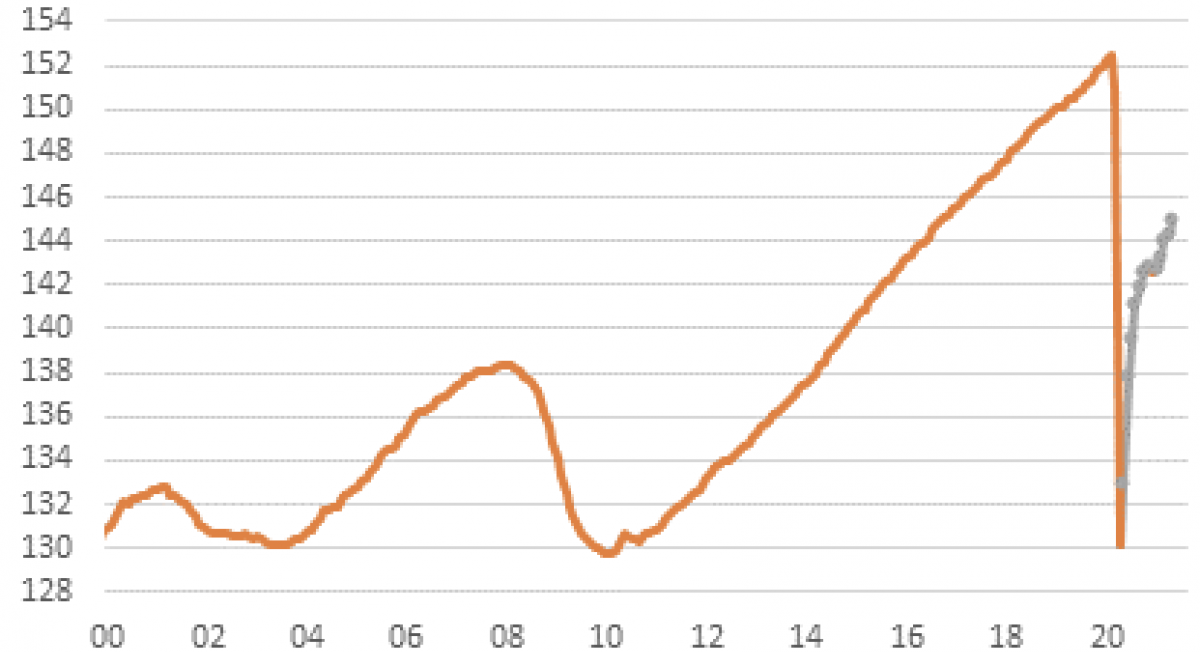

US employment levels (millions)

In millions. Dots mark from May 2020 onwards

Where are the workers?

The softness in job creation is supply related, not demand related and with wage rates picking up more than expected (0.5% month-on-month versus 0.2% consensus), there is growing evidence that the labour market will add to medium-term inflation pressures.

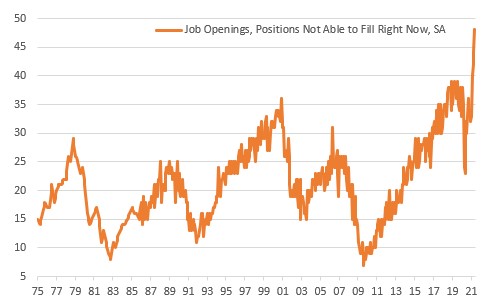

The slowdown in both the manufacturing and service sector ISM employment components was pinned on companies struggling to find suitable workers and this message was reinforced by data from the National Federation of Independent Businesses overnight. It reported the fourth consecutive new record high for the proportion of small businesses that have vacancies that they couldn’t fill. The reading of 48% is 26 points above the average for the survey that goes all the way back to 1975. The report added that 93% of companies looking to hire reported “few or no ’qualified’ applicants”.

The lack of supply of workers was also acknowledged in this week’s Federal Reserve Beige Book where “a growing number of firms offered signing bonuses and increased starting wages to attract and retain workers”.

NFIB survey - proportion of firms with vacancies they can't fill (1975-2021)

Another 3-4 months before jobs take off again

The problem was highlighted by the labour participation rate dropping back to 61.6% in May. The obvious reasons are ongoing child-care issues surrounding home schooling, which is forcing many parents to stay at home rather than go out to work. Secondly, there is also still some concern from some workers about returning given the pandemic isn’t over. Thirdly, some older workers who lost their jobs may simply have decided to retire early. Finally, there is the debate over the impact from extended and uprated unemployment benefits. They may have weakened the financial incentive of going out to work, particularly for low paid roles, especially when you factor in associated costs of commuting and any childcare.

Around half of all US states have announced they are ending them either this month or next, but for the majority of recipients they will continue until September. With the summer vacation season also kicking in this is not going to help the labour supply issue either with parents still required to stay home for childcare.

Consequently we may not see labour supply strains ease for another three or four months, which will likely keep employment growth relatively subdued in the near term. This won’t mean demand disappears, merely that those companies that want to expand and grow are going to have to pay-up to attract staff.

A full recovery is coming

We are set to see the US recover all of the lost economic output through the pandemic in the current quarter, but returning all the lost jobs is going to take many more months. As the structural rigidities in the jobs market ease we expect to see employment take-off and still forecast a December announcement of a QE taper and look for the first Federal Reserve rate hike to come in early 2023. The prospect of consumer price inflation getting close to 5% next week and core inflation hitting the highest level since 1993 means the risks are skewed towards earlier rather than later action.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

4 June 2021

It’s Oh So Quiet This bundle contains 7 Articles