Supply chain pressure to persist through 2022, leading to permanent changes in trade

Global supply chains remain under pressure. With the war in Ukraine and China’s zero Covid policy, delays and protracted supply shortages will cloud this year’s trade outlook. Goods logistics should enter a phase of moderation as delays, rerouting, high transport costs and lower consumer demand all weigh on global merchandise trade

Improvement in supply chains unlikely to last with the war and zero Covid-policy

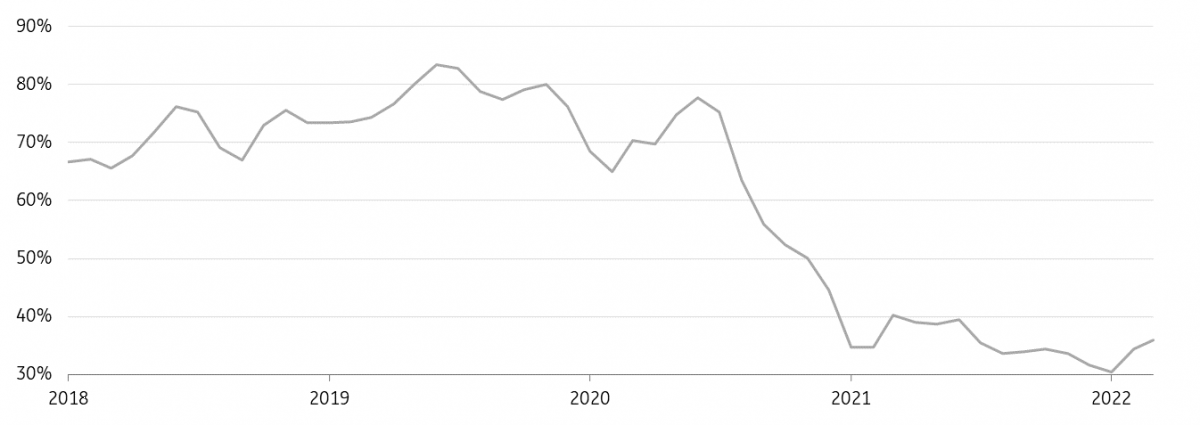

Global merchandise trade faces many headwinds this year. Although global schedule reliability, tracked by Sea-Intelligence, continues to improve slowly, reaching 35.9% in March, compared to 34.4% the month before, it remains below 2021 levels. And don’t forget that while congestion data for March captures the early effects of the war in Ukraine, it does not reflect the lockdown in Shanghai. With traffic jams having increased significantly in Chinese ports due to the zero-Covid policy in China, and in the North Sea due to the war in Ukraine, we don’t expect global schedule reliability to improve much further from here just yet. As for the North Sea region, sanctions on Russia, as well as voluntary bans, are leading to new congestion, suggesting longer-lasting problems for supply chains as sailing and air freight schemes must be reorganised, resulting in longer transportation times.

Sea Intelligence Global Schedule Reliability

Impact of long lockdown in largest global port and export area will be seen in other parts of the world later

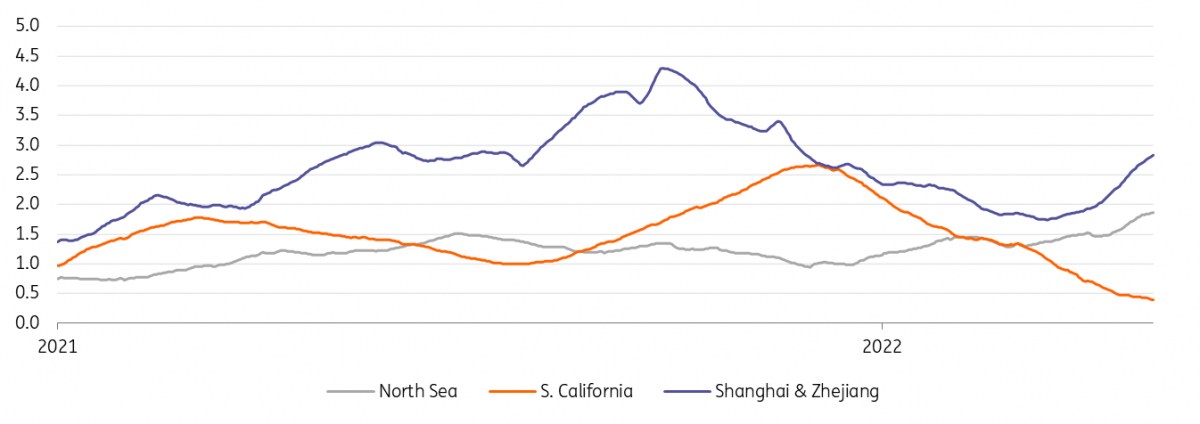

While congestion at the L.A. Longbeach bottleneck on the US West Coast improved noticeably in the first months of the year, we expect pressure to mount again in the next couple of months due to the increasing number of vessels waiting to berth outside Chinese ports, particularly in Shanghai. Container throughput dropped 25% month-on-month in Shanghai and total cargo dropped by 30%. Although a significant share of traffic was redirected to Ningbo, there is still a significant impact from the shutdowns. Data shows that container dwell times on the import side soared due to difficulties with inland connections and closed factories in the region. This creates production backlogs, leading to a wave of export traffic through the port later. Even if cargo can be cleared, it currently takes over one hundred days to get the goods from Chinese factories to the warehouses in the US and the UK. Consequently, shipping rates will remain supported at their high levels.

Share of waiting ships at important container ports as % of global capacity

Shortages of inputs and labour add to the problem

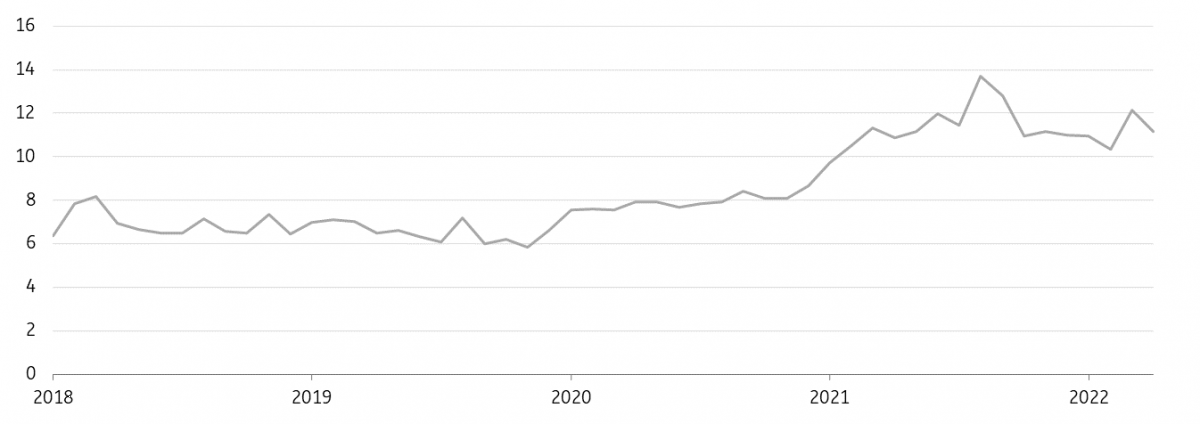

Material and labour shortages continue to hinder production and transport as well. This adds to existing material bottlenecks caused by the pandemic, while sharply increased prices make it difficult for manufacturers to calculate accurately for this year and to commit to prices for delivery to clients much later. Some 11% of goods are currently waiting on container ships globally, according to the Kiel Trade Indicator, with most of them in China. Scarcity continues in the current market environment, which leads to enduring pressures. As a consequence, average transport rates remain elevated, although spot rates have eased somewhat. This continues to contribute to higher prices for producers and consumers on top of elevated energy prices.

Percentage of goods on waiting container ships, globally

Overall, we are still facing a problem of undercapacity, mostly from the supply side. If we look at the latest global supply chain pressure index, pressures remain at historically high levels, and we don’t expect supply chain disruptions to ease substantially this year given the extremely volatile environment. Although softer demand from China, the EU and the US will ease the pressure on stretched supply chains, the current backlog is enough to keep supply chains strained throughout the year. We expect these headwinds to result in trade growth of somewhere between 1% and 2%, in our base case.

Permanent trade flow shifts face bumpy transition phase

Trade goods – permanent shifts likely due to the war in Ukraine

As a result of the war in Ukraine, we believe that trade flows will be significantly reshaped as market players who previously purchased commodities and goods from Russia look for alternatives. That said, other countries may step in and benefit from discounts. On balance, this should lead to longer sailing routes in shipping. There is already some re-routing underway for grains and energy products, for example. India, the second-biggest wheat producer after China, but not a major exporter, has stepped up its exports. World food prices surged by 29.8% in April compared to the year before, according to the United Nations Food Price Index, making it lucrative for Indian producers - who usually sell to the government at higher guaranteed prices than overseas market prices - to export. And food inflation is continuing its ascent.

However, it is not possible to compensate for everything and supply in other regions cannot always go up instantly. As our commodity experts point out, corn and soybean sowing in the US continues to progress at a very slow pace due to unfavourable weather, while soybean exports from Brazil dropped 49% year-on-year to 8.3mt in April (down 33% month-on-month) pointing to tight supplies from the South American country. Also, don’t forget about quality issues. Replacement products might not be of the same standard.

And while agricultural products can be redirected relatively easily, this might not be the case for certain industries or energy products given that the infrastructure is usually missing. Indeed, recent research shows that imports of primary goods are quite quickly substituted, but manufacturing supply chains and energy imports seem to be more hesitant to relocate, meaning that it might be more difficult to get substitutions here. Given the political pressure, however, energy imports from Russia will be replaced permanently.

Overall, we expect trade flows from Russia to Western countries which have sanctioned Russia to be ceased permanently, with some Asian, African and Southern American countries compensating for the loss of Western exports. Regarding agricultural products, the overall impact of looking for alternatives will be small for most Western countries. However, Bulgaria (24%), Romania (9%) and Latvia (7%) are major sunflower seed importers, while Latvia (28%), Denmark (10%) and Italy (8%) are major oil-cake and other solid residue importers from Russia. Regarding energy products, we don’t need to re-state Europe’s energy dependence on Russia.

The EU’s proposed ban on Russian oil would be significant for global markets

The EU is the largest destination for Russian oil, importing around 2.3m b/d in 2021, which is equivalent to around 26% of total EU crude oil imports. A phasing out of Russian oil would mean that European buyers have time to look for alternative sources, and so allowing for a more orderly change in trade flows. Whilst still supportive for prices, it should limit the upside in the market, compared to an immediate ban. However, it will still be a difficult task for EU countries to wean themselves off Russian oil. Firstly, there is the potential for logistical issues, given that some Central and Eastern European countries are heavily reliant on Russian pipeline oil supply, and countries would need to ensure they have the necessary infrastructure to switch to other sources of supply, particularly those countries which are landlocked. Secondly, EU refiners will want to source crude oil of similar quality to Urals (which is a medium sour oil) in order to minimise the impact on refinery output. This could make the change in trade flows more complicated. Then importantly, the global oil market is tight at the moment, and OPEC up until now has been unwilling to aggressively tap into its spare production capacity. Therefore, EU refiners will need to rely on a change in trade flows, where the likes of China and India increase their share of Russian oil purchases (the large discounts for Urals should provide enough of an incentive to do so), which would help to free up other supply for the EU.

However, there are risks. We will need to see how much of an appetite these buyers have to increase their Russian oil purchases. And even if they are willing, there is the risk that further down the road we see the US imposing secondary sanctions on Russian oil, which would make it difficult for any buyer to purchase Russian oil. Under this scenario, the market would be much tighter, given the potential for more significant Russian oil supply losses. The EU is also a significant importer of Russian refined products, which is included in the proposed oil ban. It would be more challenging for the EU to find alternative refined product supply, particularly when it comes to middle distillates, and this is likely the reason why the EU is proposing a longer wind-down period for refined products. The middle distillate market is extremely tight in most regions around the globe. Risks around Russian supply, lower Chinese exports, recovering demand following Covid, and the limited ability of refiners to respond have meant that inventories in the US, Europe and Asia are at multi-year lows.

Trade routes – temporary bypass

The Black Sea region is not only the ‘breadbasket’ region, but is also one of 14 global chokepoints, as identified by Chatham House, where exceptional amounts of global food pass through. With Ukrainian ports being closed to the war, it is currently extremely difficult to get grain exports through this route. Recently, accumulated small volumes of corn from Ukraine could be exported via Romania for the first time since Russia invaded Ukraine. But this is resulting in longer transportation times and higher costs. Attempts will also be made to shift part of the grain exports from Ukraine to Europe by rail, but this makes up only a fraction of grain transports.

Since commodities are not shipped through the air, and airfreight is an expensive option, congestion in shipping can only be offset via air in specific cases. Then again, the closure of airspace leads to new capacity reductions. Russian freighters are being dropped out of global service, and routes between Europe and destinations in Korea and Japan are being redirected to avoid Russian airspace, meaning longer hours and possible stopovers, which once again leads to inefficiency, new capacity pressure and higher costs. All of this results in higher prices.

Consequently, while we expect trade flow shifts to be permanent, we do expect trade routes that are currently being blocked to resume their transportation functions as soon as the war is over.

More self-sufficiency wanted – but economically not needed and a time-consuming process

Another trend, which will now gain further momentum, is the shift towards more self-sufficiency. The pandemic has already kickstarted this process, with the European Union for example introducing the European Chips Act in order to secure sovereignty in semiconductor technologies and applications.

Yet, although headline-grabbing, the shift towards more self-sufficiency is unlikely to show up in trade numbers for the time being as, so far, this has affected only some areas deemed critical, such as microchips or certain commodities. Also, this trend is more of a long-term story, as it takes a great deal of time to set up new industry branches. China has been on this path for years.

Ultimately, the war in Ukraine might result in a new world economic order, being characterised by more ‘friendshoring’ as labelled by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen – trading relationships with countries who have long-standing relationships, cooperation and share similar values might become more valuable. Ethics may also become a more important consideration in trading.

Overall, conditions for international trade remain very tough and the low costs and perceived low risks (both political, and logistical) which helped to support the development of global supply chains have become sources of uncertainty. However, these supply chains remain intact for now. It’s more about rerouting, diversification in suppliers and or regions, more stockpiling, and inventory building. In the US, for example, warehousing utilisation increased by 32% in March 2022 compared to March 2020, according to data from March’s Logistics Manager’s Index Report. Changes in inventories in the eurozone were up by 95% in the fourth quarter compared to the previous quarter, climbing to the highest level since the beginning of the time series in 1995.

Importers are considering options to mitigate supply risks and improve supply chain reliability (buffer stocks, multi-sourcing, nearer sourcing), but this is a slow process and it’s not easy to match the advantages of past trade relationships, as alternatives could prove to be more expensive. On top of that, we face (labour) shortages. Right now, it is a matter of planning further ahead than ever before.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article