Sterling crisis: A look at the unpalatable policy options

Sterling has fallen close to 10% on a trade-weighted basis in a little under two months. That's a lot for a major reserve currency. And traded volatility levels for the pound are those you would expect during an emerging market currency crisis. We take a look at the (unpalatable) policy options available to stabilise sterling

Defining a crisis

Unlike equity markets where in excess of a 20% fall from a peak is called a bear market, definitions in FX markets are a little looser. Suffice to say that GBP/USD is the worst performing G10 currency this year at -20% year-to-date, just pipping the Japanese yen to that position. (Japan intervened last week to support its currency for the first time since 1998).

Typical emerging market currency crises since the early 1990s have seen exchange rates fall anywhere near 50-80%. The large size of these adjustments has typically been a function of the breaking of an exchange rate regime/peg. The UK has learned from its experiences in ERM II in 1992 and has operated a free-floating FX regime ever since – arguing against sterling following some of the outsized EM FX adjustments outlined above.

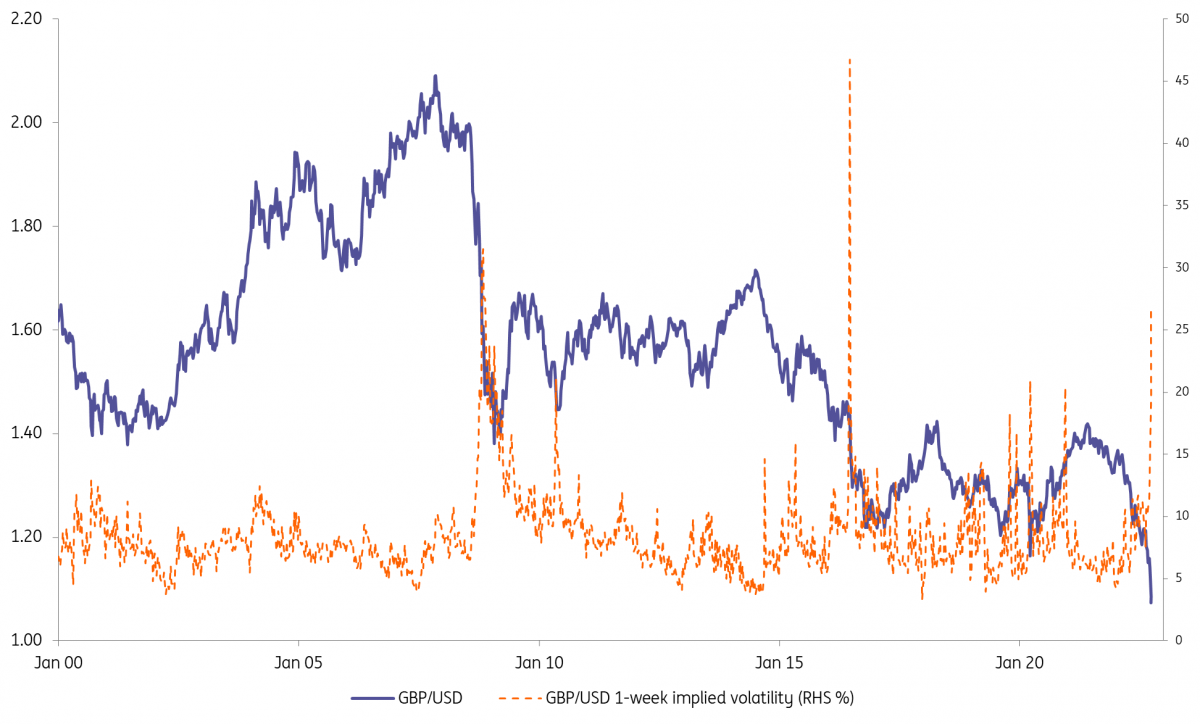

However, the 3.5% decline in Asia overnight and the now 28% levels for one week traded GBP/USD volatility (close to the highs in March 2020) certainly marks trading out as ‘disorderly’. Disorderly markets normally prompt a response from policymakers.

As we go to press, headlines suggest that the Bank Of England (BoE) is considering making a statement later today. Below we take a look at the possible policy responses and their likelihood.

GBP/USD sinks towards parity - one week volatility surges

Sterling stabilisation measures – a look at the policy options

- Fiscal U-turn. Comments from the UK government over the weekend that the Treasury is mulling further tax breaks in coming months, would suggest ministers are unlikely to change course imminently. But mounting pressure, perhaps coupled with comments from rating agencies over coming weeks, means investors will be looking for signs of at least a partial policy U-turn. Ministers may emphasise that tax measures will be coupled with spending cuts, and there are hints at that in today’s papers. We also wouldn’t rule out the government looking more closely at a wider windfall tax on energy producers, something which the prime minister has signalled she is against. Such a policy would materially reduce the amount of gilt issuance required over the coming year.

- BoE to suspend QT. First inflation, then fiscal concerns, and finally a broader run on sterling and sterling-denominated assets. In all three cases, gilts have been at the wrong end of the stick. One particular concern for gilts is policy cooperation between the Bank of England and the Treasury. Be it on inflation, fiscal, or on confidence in the currency, markets have the distinct, and unnerving, impression that the two institutions in charge of economic management in the country are working at cross purposes. Gilts are caught in the crossfire. Despite this list of legitimate macro concerns, we also suspect that the magnitude of the move in gilts these past days (adding up to roughly 100bp moves at the front-end of the curve in two days) has been magnified by worsening liquidity. We have been highlighting the deterioration in gilt trading conditions all year. The BoE has added fuel to the fire by seeking to reduce its gilt holdings. In an environment where private investors are justifiably nervous about greater gilt issuance, and also greater gilt riskiness, the BoE is adding to gilt supply, and will soon engage in outright sales. A low-hanging fruit, in our view, would be to suspend quantitative tightening until market conditions improve.

- Emergency BoE rate hike. The collapse in sterling over recent days has unsurprisingly sparked expectations of an inter-meeting rate hike. That should not be ruled out, though we suspect the committee will be reluctant. Thursday’s BoE decision suggests the BoE is – rightly or wrongly - less concerned about sterling than a lot of market commentary is suggesting they should be. As a rough guide, the 7-8% fall in trade-weighted sterling since the start of August, if persistent, would add somewhere between 0.6-0.8ppt to inflation at its peak. That’s not insignificant, but is it enough in itself to necessitate an inter-meeting hike? Probably not. But the key question is whether an emergency rate hike would do all that much. Certainly, it would need to be bold, and likely in excess of 75bp. A bold rate hike would prompt further complications, too. Rate hikes of the magnitude now being priced by investors would start to be highly problematic for mortgage holders and corporate borrowers. While the vast majority of UK mortgages are fixed, around a third of those are locked in for less than two years. For corporates, the BoE estimated last year that 400bps worth of rate hikes (from near-zero) would take the proportion of firms with low-interest coverage ratios to a record high. In the first instance, we’re more likely to see BoE hawkishness channelled through speeches this week, emphasising that it can move more forcefully if needed in November. Indeed, the pendulum is increasingly swinging towards a 75bp hike (or perhaps more) at that meeting. We would also say that the BoE may be psychologically scarred from the events in 1992, where defensive rate hikes failed to keep sterling in the ERM II mechanism.

- FX Intervention. Last week Japan intervened to support their currency for the first time since 1998. We do not think FX intervention is a credible option for the UK. The UK only has net FX reserves of $80bn, less than two months’ worth of import cover. The adage in FX markets is that no intervention is better than failed intervention. Instead, we may see building interest in the G20 central bankers and finance ministers meeting on 12 October. Will the FX language in the Communique get tweaked to show concern over disorderly dollar strength and hint at joint FX intervention?

- Dollar swap lines. Typically in a currency crisis, we hear about the need for additional access to dollar funding through dollar swap lines. For reference, the BoE already has a permanent and unlimited dollar swap with the Federal Reserve. However, these lines are designed to provide support for dollar funding challenges and not for Balance of Payments needs. Dollar funding does not seem to be a problem for UK banks, but the BoE could make a pre-emptive move here by re-introducing an 84-day dollar auction in addition to the current 7-day facility.

- IMF Flexible Credit Line. Given many references to Friday’s UK budget being the most generous since the Barber budget of the early 1970s, there will, unfortunately, be comparisons drawn to the UK seeking an IMF bailout in 1976. We assume the stigma of going to the IMF would prompt some aggressive UK policy adjustments beforehand, but just for reference, a good quality credit, Chile, (sovereign-rated A/A-) recently received an $18bn ‘precautionary’ Flexible Credit Line (FCL) from the IMF, joining the likes of Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Poland. Chile’s FCL was eight times its IMF quota. The UK receiving eight times its IMF quota ($200bn) would seem unlikely in that the IMF already has a total of $144bn lent out according to some estimates and the lack of conditionality of an FCL may not be a good signal given the nature of the sterling crisis.

- Capital controls. Highly unlikely. Capital controls have been used by Russia this year to support the rouble. But Margaret Thatcher dismantled capital controls in the UK in 1979. A reversal of such measures would be a complete anathema to the new Truss government’s agenda of deregulation and liberalisation.

At this stage, we think UK authorities will probably just have to let sterling find its right level. The UK has a reserve currency so it can always issue debt – it’s just a question of the right price.

We are still bullish on the dollar this year as Fed leads the deflationary charge and global growth slows. That means GBP/USD is now vulnerable to a break of parity later this year, while - quite unexpectedly - EUR/GBP can make a run towards the March 2020 high of 0.95, with outside risk to the 2008 high of 0.98.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article