Singapore and Malaysia enjoy lowest inflation in Asia

Macroeconomic policies have kept a lid on inflation in Singapore and Malaysia. A backdrop of continued benign inflation and the increased threat to growth from the US-China trade dispute mean that Singapore's central bank tightening in April hangs in balance, while we don’t expect Malaysia’s central bank to change policy until after 2019

Persistent low inflation in October

Released today, the October consumer price data from Singapore and Malaysia showed no departure from the low inflation trends these economies have been enjoying this year.

Singapore data surprised on the downside with an unchanged headline CPI inflation rate of 0.7% year-on-year, as against the consensus forecast of a pick-up to 0.8%. Malaysia’s 0.6% print was in line with consensus, though it was double the September rate, which was largely due to the low year-ago base effect rather than current price pressure. Core inflation ticked up in both countries to 1.9% from 1.8% in Singapore, and to 0.4% from 0.3% in Malaysia.

Why is Singapore's core inflation outpacing the headline rate

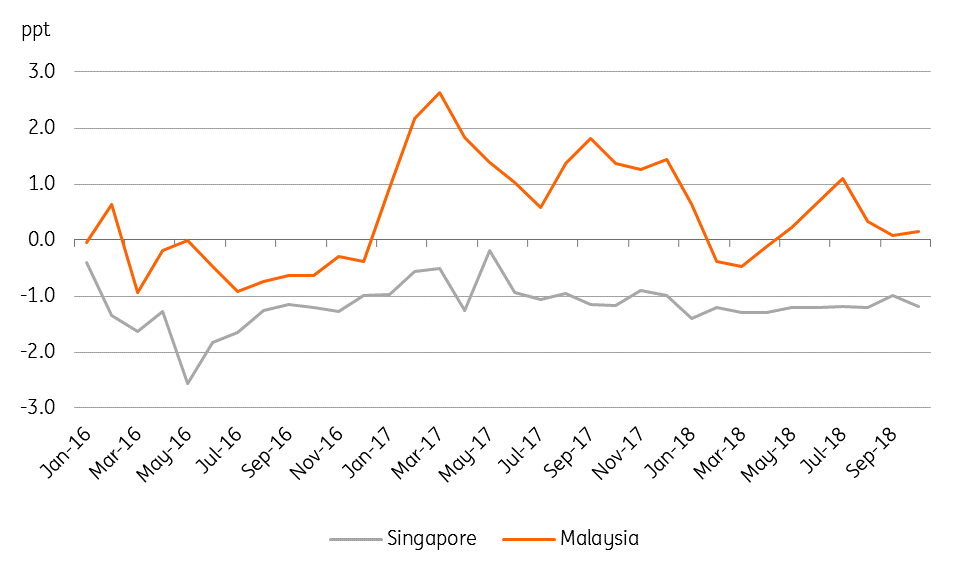

A wider gap between the headline and core inflation rates in Singapore than in Malaysia (see figure) is explained by the differences in the way core measures are calculated in both countries. Why is Singapore's core inflation running above the headline rate?

Unlike the convention of leaving out food and fuel prices in estimating core inflation, Singapore’s core CPI strips out the accommodation subcomponent of housing and the private road transport subcomponent of transport. Inflation in both of these subcomponents has been in negative territory for over half a decade now. The quarterly budget rebate of Services and Conservancy Charges (S&CC) for public housing and falling Certificate of Entitlement (COE) premiums for cars were further drags on these CPI components in October.

Headline minus core inflation

Decoupling of food price inflation

There is also some decoupling evident in recent years in food price inflation in the two countries. Singapore’s food price inflation was closely correlated to that of Malaysia’s until a couple of years ago. The relation appears to have broken down since 2015, though this doesn’t mean Malaysia ceased to be a key source of food supplies to the City State.

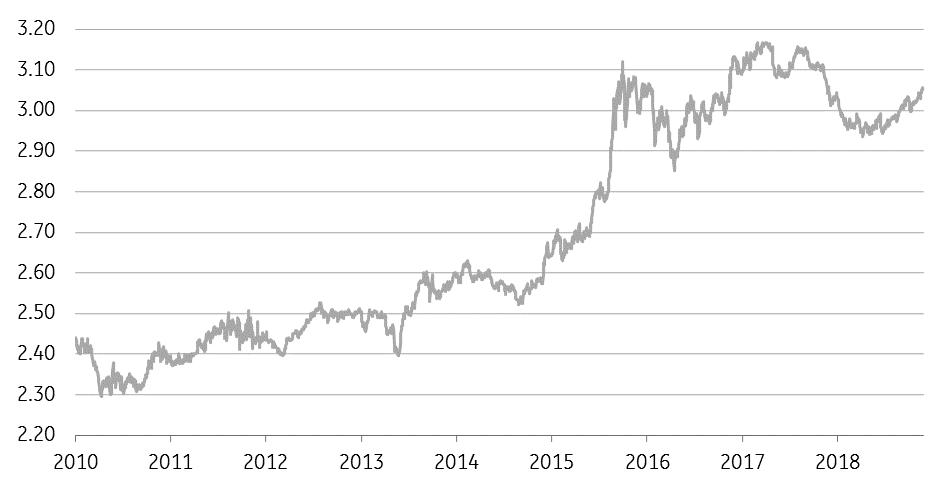

The decoupling could be part of a significant depreciation of the Malaysian ringgit (MYR) against the Singapore dollar (SGD) in the wake of the 2014 commodity price crash (see figure), making Singapore’s imports from Malaysia a lot cheaper.

Food price inflation in Singapore tracked that of Malaysia, but not anymore

Malaysian ringgit per Singapore dollar

The macro policy lid on inflation

In Singapore, macro-prudential tightening of policies for the housing and private transport sectors have completely killed price pressure in these sectors. And the property cooling measures already in place were tightened further in July this year, intensifying the downtrend spiral on housing prices. These policies are unlikely to go away anytime soon, while the authorities continue to be concerned about resurgent inflation, especially core inflation, possibly owing to the fact that Singapore remains among the most expensive cities in the world.

In Malaysia, the elimination by the Mahathir government of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) was a big dent to inflation. And the replacement of the GST by a more benign Sales and Services Tax (SST) from September barely impacted inflation. The results of these administrative measures will continue to linger at least through mid-2019. The government anticipates inflation in a 1.5-2.5% range this year and 2.5-3.5% in 2019. Indeed, these forecasts reinforce an extremely loose fiscal policy that will eventually fuel price pressures. But we don’t see inflation becoming an imminent threat, at least not until mid-2019 when the impact of GST elimination moves out of the base of comparison. Average inflation in the first nine months of 2018 was only 1.1%. Our full-year 2018 forecast is 1.0%, while we recently cut that for 2019 to 1.6% from 2.0%.

Future policy course

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) was among the first Asian central banks to begin monetary tightening in April this year by moving policy from a neutral or zero appreciation of SGD nominal effective exchange rates (SGD-NEER) to a stance of ‘modest and gradual' appreciation within an unspecified policy band. The MAS didn’t stop there though despite the intensified risk to the economy from the global trade war; it tightened again in October by ‘slightly’ increasing the slope of the SGD-NEER policy band.

Singapore’s GDP growth has started to slow from the third quarter as weak exports dampened manufacturing output. The recent rout in technology stocks in the US clouds the prospects of the tech-heavy Singapore manufacturing sector and GDP growth, which will make it hard for the MAS to remain on its tightening course in 2019.

The Malaysian economy is just as vulnerable to risks from the global trade war and the downturn in the global electronics cycle. Loose fiscal policy should do some of the heavy-lifting in supporting GDP growth above 4% in coming years, while a benign inflation backdrop should allow the Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) to maintain its policy accommodation for the economy. We aren’t expecting the BNM to move its overnight policy rate, currently 3.25%, until after 2019.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

23 November 2018

Good MornING Asia - 26 November 2018 This bundle contains 3 Articles