Rising carbon prices increase viability of low-carbon technologies

Carbon reduction strategies will be a key focus for many businesses this year. But challenges await, as both mandatory and voluntary carbon markets are far from perfect. In Europe, current carbon price levels support the business case for green technologies like Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), unsubsidised solar PV systems and wind energy

Carbon pricing: a priceless solution to the tragedy of the commons

A healthy and sustainable climate is a common good that requires everyone to do their part. Yet so often, companies pursue their own short-term gains at an ultimate cost to the many, a problem in economics known as the 'tragedy of the commons'.

This is a particularly pressing concern for carbon emissions. In most cases, the emitting company does not pay in full for the damage it causes, like air pollution, or the physical impact of climate change. In economic terms, the cost of carbon emissions to society is higher than the private cost to the polluter, which all but guarantees higher emission levels than the climate can sustain.

The solution is simple, in theory. By putting a price on carbon equal to its social cost, emissions are likely to be reduced to levels that the earth can sustain. That’s a solution corporate leaders and policymakers are increasingly relying on in their race to a net-zero economy, as it provides them with a tool to reduce emissions in a cost-effective way, as seen in Europe and China.

This article provides a quick guide to carbon pricing for corporate decision-makers who will have to address this issue head-on in the coming years.

Mandatory carbon markets are increasingly a topic for corporate decision-makers in manufacturing and the energy sector…

Governments around the world are starting to price carbon by imposing mandatory carbon markets on energy-intensive sectors, notably the power sector and manufacturing such as steel, cement, plastic and petrochemical industries. According to the World Bank, the number of carbon pricing schemes around the globe increased from 19 in 2010 to 64 today.

In theory, these carbon pricing schemes are effective for two reasons. First, they are mandatory, with governments forcing the targeted industries and companies to comply. Second, the emissions reduction target is met by design. The yearly emissions cap is decreased over time in line with the targeted level for emissions in the future.

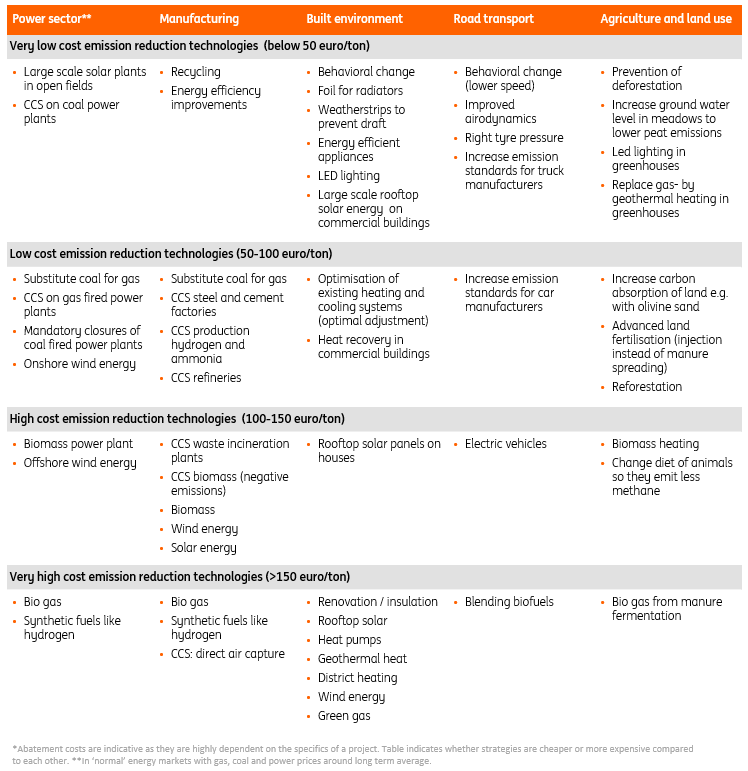

Carbon pricing schemes are also efficient, as the market decides the mechanism for reducing emissions. Companies will first apply the most cost-efficient measures, such as cheap energy efficiency technologies (think of insulation, led lighting or recycling) and behavioural change.

More costly technologies are employed when the reduction targets cannot be met with the cheapest options. As the overall emissions cap is reduced over time to limit carbon emissions, the carbon price rises. And with higher carbon prices, the business case for low carbon technologies becomes more viable.

Europe's carbon price tripled in 2021 to €90

European carbon price in mandatory EU ETS market in euro per ton carbon

In Europe for example, the business case to capture and store carbon (CCS) is becoming feasible at current carbon prices, above €80 per ton of CO2, particularly in carbon-intensive manufacturing clusters where governments and grid operators build the infrastructure to transport carbon.

Carbon pricing favours emission reduction strategies with low abatement costs

Indicative carbon abatement costs in euro per ton CO2 in Europe*

The European Commission is exploring ways to extend mandatory carbon pricing to other sectors such as shipping, road transportation and buildings. If it follows up with action, carbon pricing will also become relevant for corporate decision-makers in sectors like shipping, road transportation and real estate. Note however that the abatement costs (the cost of removing undesirable byproducts created during production) for many technologies in these sectors are generally much higher compared to manufacturing and the power sector.

…and carbon markets need to be strengthened to reach the Paris Climate Goals

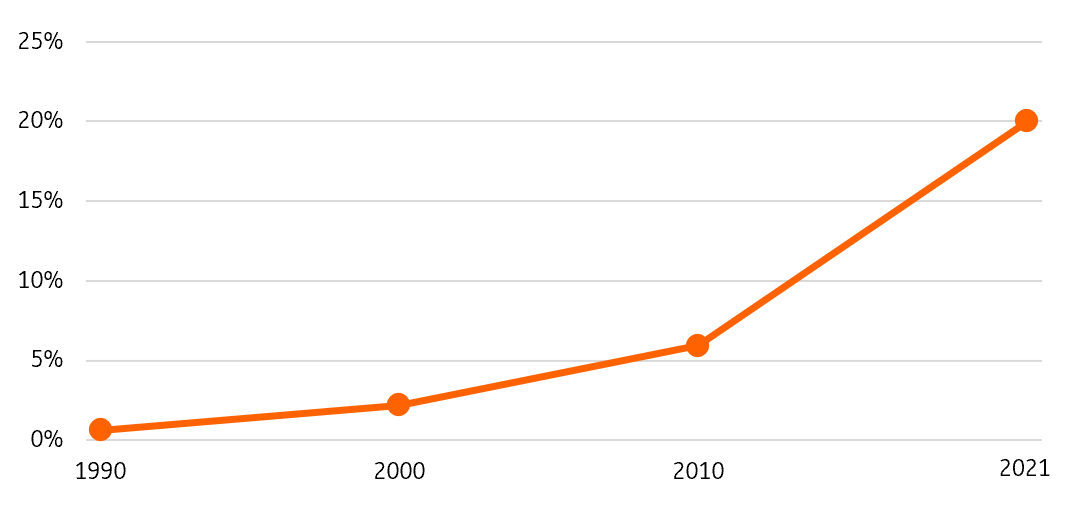

21.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions were covered by carbon pricing instruments in 2021, according to the World Bank’s carbon pricing monitor. That represents a significant increase from 2020, when only 15.1% of global emissions were covered.

One fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions are currently covered by mandatory carbon pricing

Share of global emissions covered by mandatory carbon taxes and emissions trading schemes

However, just under 4% of these emissions are priced within the €35-70 range per ton of CO2 that is currently needed to meet the 2˚C temperature goal of the Paris Agreement. No emissions in carbon pricing schemes are priced around €130-140 per ton of CO2 that the World Bank considers to be in line with the 1.5˚C target.

So, the vast majority of global greenhouse gas emissions (almost 80%) is not priced at all. And the carbon price is usually too low to bring emissions in line with the climate goals. Corporate decision-makers should anticipate an increase in carbon pricing if policymakers stick to the Paris Climate Goals.

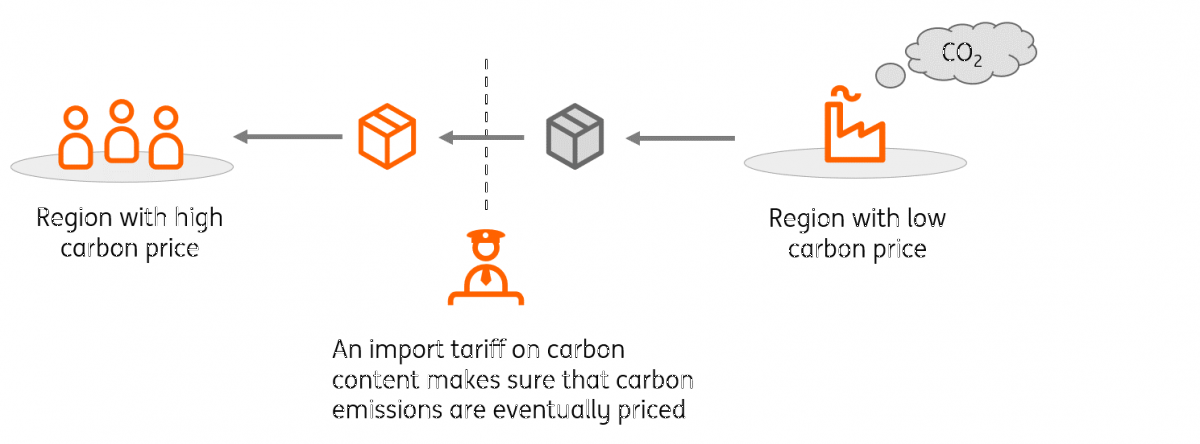

Carbon border taxes could become an issue in competition with foreign companies

Mandatory carbon markets are local by definition as governments cannot act outside their jurisdictions. There is no global carbon market as a result.

Jurisdictions across the globe have their own carbon pricing mechanisms that result in different carbon price levels. For example, carbon prices currently stand at around €90/ton in the EU, about €72/ton in the UK, about €28/ton in California and around €6/ton in China.

Different prices levels create incentives for corporate decision-makers to relocate carbon-intensive activities towards regions with no or low carbon prices. It also works the other way round, providing incentives to keep existing activities in those regions. In both cases, carbon-intensive products are then imported back into the jurisdictions with higher carbon prices, a process called carbon leakage.

Hence the need for Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms (CBAM, a proposition by the EU Commission) to ensure a level playing field between major production and trade regions such as the European Union, the US and Asia (notably China and India). Of course, there wouldn’t be a need for border adjustments if all major production regions in the world priced emissions locally and more or less at the same price.

A carbon border adjustment mechanism prices carbon emissions equally across the globe

The CBAM is a tariff on imports in line with the embedded carbon content of the product, which has not been taxed in the country where the good is produced. It ensures that the carbon emissions are eventually priced.

It also provides governments in producing countries with an incentive to increase carbon prices, as the CBAM would allow them to reap the tax benefits of the carbon policies themselves rather than allowing other countries to benefit from import taxes. That could bring about much-needed global coordination between countries to align climate policies and carbon prices. In the meantime, corporate decision-makers might include CBAM in their competition and pricing strategies.

Voluntary carbon offsetting schemes could be on the agenda…

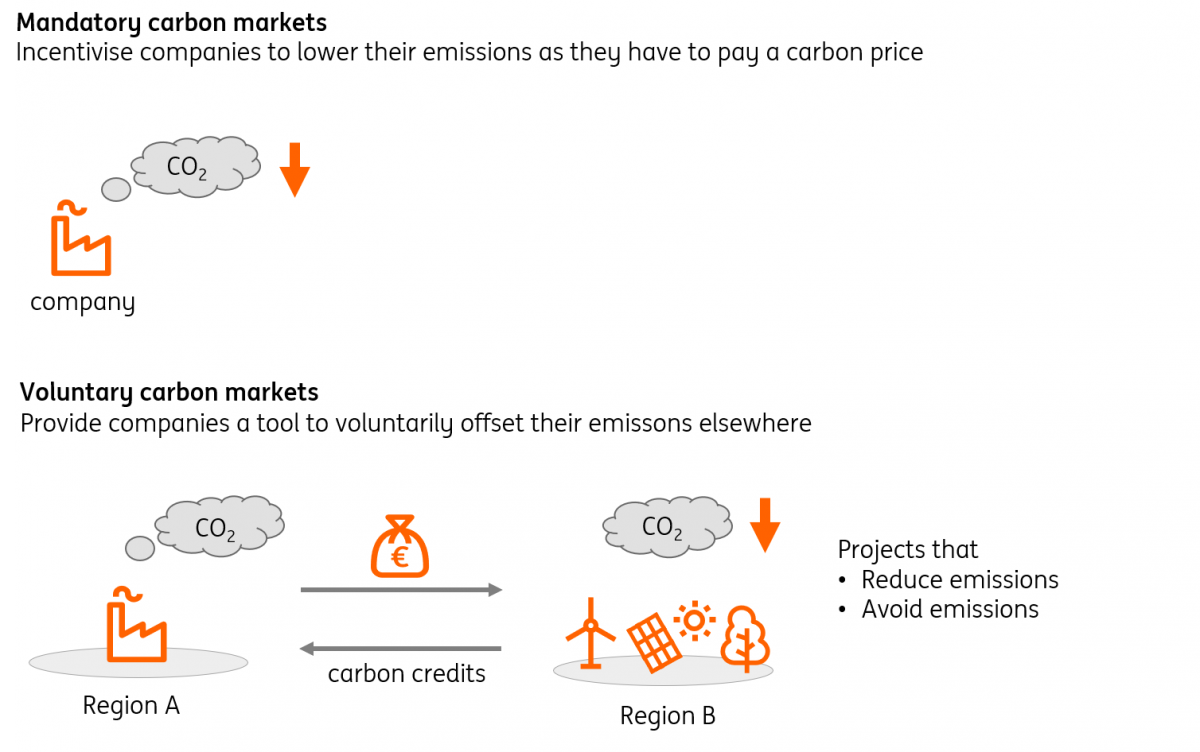

Currently, most mandatory carbon pricing schemes apply to the power sector and manufacturing. Still, with increasing pledges to net-zero strategies, a growing number of companies are looking for ways to reduce or offset their emissions, whether or not they are already subject to mandatory schemes. They can do so in voluntary carbon markets.

Voluntary carbon markets (in short VCMs) are initiatives that facilitate trade in emission units, called carbon credits, generated from emission reduction activities. Companies can participate in a VCM either individually or as part of an industry-wide scheme, such as the CORSIA.

Two ways to incentivise companies to lower carbon emissions

Mandatory versus voluntary carbon markets

VCMs are often initiated by non-governmental bodies, as opposed to mandatory carbon markets that are set up by governments. VCMs often involve multiple countries. Usually one country has much lower abatement costs than the other country. Hence, VCMs provide a way to offset emissions in regions with the lowest abatement costs and direct green investment from richer to poorer regions.

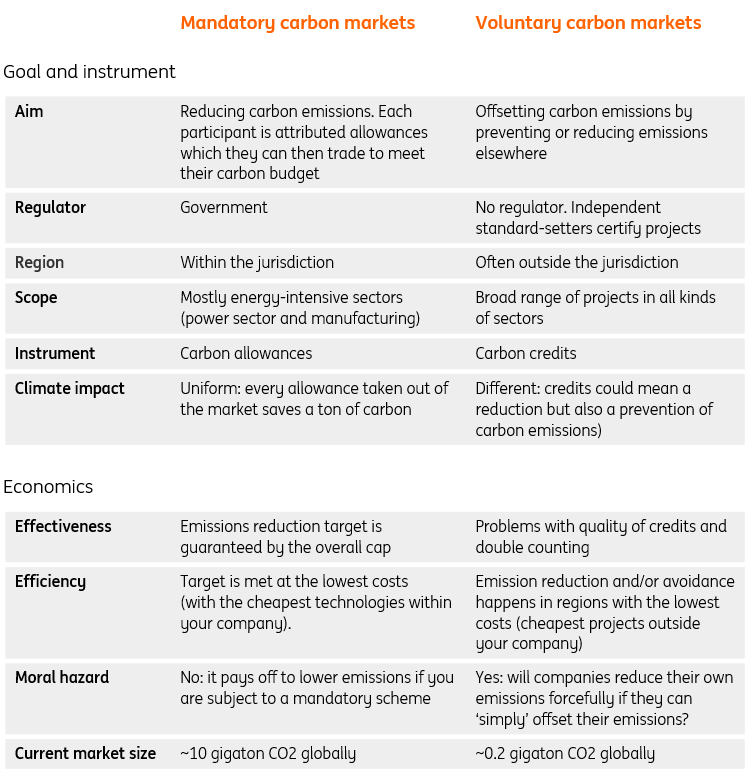

Main differences between mandatory and voluntary carbon markets

Differences on goals, instruments and economics

Carbon credits can be grouped into two categories dependent on the type of offsetting project that generates the credits:

Avoidance projects avoid emitting greenhouse gasses. Projects to prevent deforestation are a case in point; they don’t reduce emission levels but they prevent net emissions from rising as felled trees can no longer capture carbon.

Removal projects aim to actually reduce current emission levels.

So the quality of carbon credits differs in VCM. Removal projects tend to trade at a premium to avoidance credits. Corporate decision-makers need to take this into account as not all carbon credits are considered effective and credible emission reduction strategies by shareholders, like NGOs, or employees.

One possible drawback from VCMs is that companies may behave less responsibly towards climate change if they can simply offset their emissions instead of having to reduce emissions themselves the hard way (moral hazard). Mandatory carbon markets simply force companies to lower their emissions or to pay a fine for it in terms of the carbon price.

Will companies voluntarily reduce emissions if they have the option to offset elsewhere?

Moral hazard dilemma in voluntary carbon markets

…now that COP26 reconnects mandatory and voluntary carbon markets

In the past, under the Kyoto protocol, there was a link between mandatory and voluntary carbon markets. In Europe for example, owners of power plants and factories in heavy industries could convert offsetting credits (Certified Emission Reductions, CERs) to carbon allowances in the EU Emissions Trading System.

This link was removed due to long-standing double-counting concerns about the quality of offsetting projects, mismanagement of projects, double-counting of credits and even fraud.

After years of negotiations, in the autumn of 2021, COP26 agreed on a rulebook to eliminate most of these issues, referred to as Article 6 of the treaty. This is a little known, and technically complex, set of rules to strengthen VCMs. Hence we dedicate a separate article to it.

If implemented well, Article 6 could re-establish the conversion of offsetting credits to carbon allowances, putting both on the agenda of corporate decision-makers.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

19 January 2022

Higher risks, higher costs, higher wages This bundle contains 6 Articles