QE in emerging markets: The unconventional risks

Central banks typically engage in bond buying as a last resort, when the official rate has hit zero. Not in emerging markets. Here, some central banks have dived into QE programmes with rates well above zero. So what's the effect? This article is taken from our full report which you can download here

Doing QE the EM way

Central banks typically engage in bond buying as a last resort – when the official rate has hit zero. Not in emerging markets. Here, some central banks have dived into QE programs with rates well above zero. The dominant rationale centres on a desire to stabilise markets as fiscal pressures build, typically pandemic-related. In many cases it is sterilised, or mopped up through bills issuance, but not always. In the end, additional money is being printed through central banks bond buying. We survey the risks. There are some. Some central banks have quite large programs, others are engaging in QE from an already vulnerable state. Then again others are small and reversable. One thing is sure; they need monitoring

Quantitative Easing programs ongoing in Emerging Markets

These are our estimates of what EM central banks are doing in terms of QE size

Emerging markets are different

QE is the equivalent of printing currency. Printing more currency increases its supply, and should therefore lower its price. The US and other core central banks have managed to execute QE without a material adverse effect on FX, partly as their underlying currencies are underpinned by a muscle memory of relative macro stability. The USD is of importance here. It is the global reserve currency, and we find during times of crisis that there is excess demand for it. That’s a luxury position from which to execute QE. The likes of the EUR and the JPY tend to trade as a stationary series around the USD on their respective crosses – big swings, but typically mean-reverting. And since they are all at QE there isn’t much for them to depreciate against.

But emerging markets are different. Here FX rates are trending, typically reflecting wider inflation differentials, on top of the tendency for capital flight when policy wobbles, which in turn produces echoes and overshoots. Now throw in a dose of QE and you have a further excuse for vulnerability. The question is, to what extent are risks being run.

Jumping in at the deep end

For emerging markets (EM), the Quantitative Easing (QE) button has been pushed with rates well above zero in many cases (Figure 2). None of the central banks in question went in to QE with rates actually at zero, although Croatia and Chile were practically there, and Poland has gotten there belatedly.

Policy rate obtained when QE was enacted (%)

QE impact partly depends on the starting point

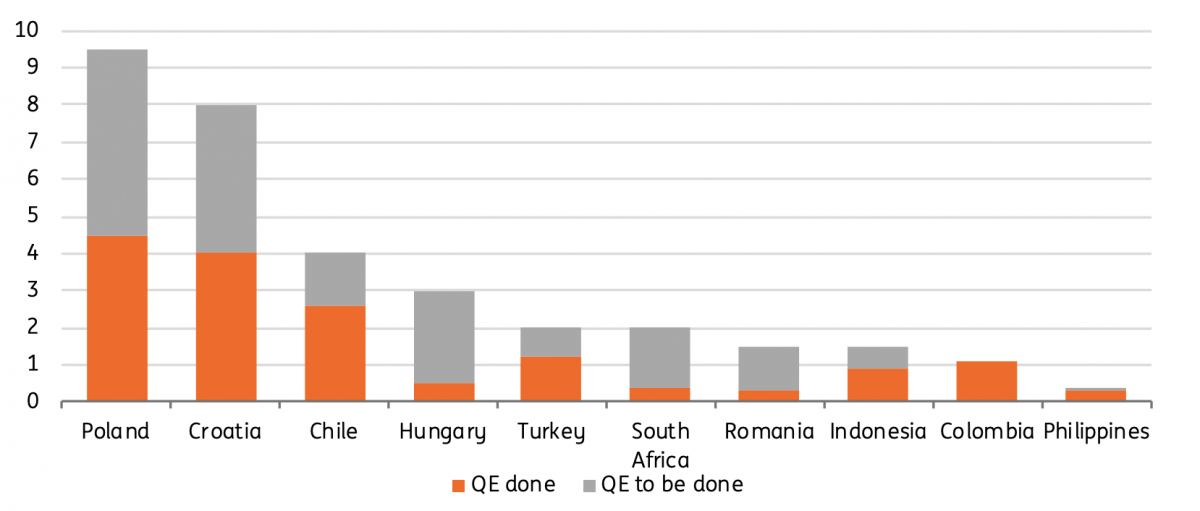

Emerging market central banks that have kicked off QE are a real mixture of players. Many of the central banks are not telling us how much they are doing, or indeed intend to do. Below is a combination of what is known plus estimates.

Size of QE programs in EM (% GDP)

Country comparisons

At one extreme of the credit spectrum is Poland, and probably Israel. These central banks are buying government bonds and are unlikely to cause too much consternation for their markets, provided macro stability is maintained. That said, Poland, in particular, is not invulnerable by any means. It runs a risk by virtue that it is running the biggest QE program in EM space, potentially posing FX risks at some point in the future.

Hungary comes after that. Here policy here is aimed at financial market stability with a dose of yield curve control to aim fiscal management. A central goal is to be able to control the long-end of the yield curve, providing cheaper, less volatile funding for the Hungarian budget. It is not significant in size, but also far from insignificant.

Then comes Chile, which is largely providing bank support through loans; theoretically equivalent to bank bond-buying, but baby steps in QE terms. And Colombia which is buying corporate bonds (but just out to 3 years). Meanwhile, Brazil is paving the way to make QE possible, but there is no certainty they would employ it. It is tempting now as market rates have fallen, but more tempting should conditions re-deteriorate.

Then we have the likes of The Philippines, Indonesia and South Africa. They are all buying government bonds. The sizes here range from small to unspecified, with the largest vulnerability attached to the latter. The likes of South Africa buying bonds right along the yield curve for unspecified sizes is great for the short term as there is a big buyer in play but poses risks from a medium-term perspective. At the other end of the scale, the Philippines is only buying out to 6 months in maturity, just toe-dipping.

That said, even where QE is short-dated or small in size, it is also a starting point to potentially expand from. For more grandiose QE projects, statements are being made. Romania is one of those names that has re-established credibility in the past decade and has been rewarded with a return to investment grade. But it is now in a vulnerable phase, where there is a rating threat.

Apparent ability to control the currency helps, but a step too far into the temptation of QE runs risks. Should QE go on for a period of time without an FX reaction, that does not mean there will not be one. Reaction can still come in an exaggerated way at a moment of future vulnerability. The fact that this has not happened so far does not mean it won’t happen; stuff like this tends to build until it gets to a “sit up and notice” moment.

Download our full report here

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

8 June 2020

In case you missed it: There may be trouble ahead This bundle contains 10 Articles