Philippines: Missing the remittance cushion

The Philippines relies heavily on overseas Filipino workers remittances, but with Covid-19, we expect remittances to fall by up to 6.9% in 2020. As the government resumes import-intensive infrastructure programme too, we believe the current account deficit is likely to widen substantially to $6.3 bn from -$460m last year

| -6.9% |

Projected OFW remittance growthIn 2020 |

The current account records the flow of goods, services and transfers between residents and non-residents.

For the Philippines, an economy that routinely posts trade deficits, the current account is largely dependent on secondary income, which is supplied by remittances sent home by Filipinos working outside the country. Overseas Filipino Worker (OFW) remittance flows have been a steady source of foreign exchange and purchasing power for the Philippines over the past few decades.

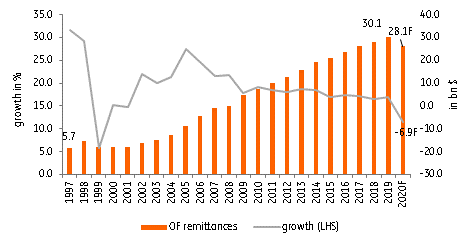

From a mere $5.7 bn back in 1997, OFW remittances have grown at an average rate of 9.3% over a span of 22 years while registering 18 straight years of growth since 2002.

Philippine remittances (volume and growth rate)

Overseas Filipino population is as big as Austria's

Official records vary but we estimate that c.9.2m Filipinos are based overseas, roughly equal to the population of Austria.

On average, each Filipino sends home $267 a month with cash remittance flows totalling $30.1bn in 2019. Of the 9.2m, only 2.4m are registered with the government with the balance classified as non-registered OFWs or as Filipinos who may have established permanent residence in another country but continue to send remittances to their families.

Filipinos are everywhere (pretty much)

Filipinos live across the globe with remittances sent from Europe, the Americas, the Middle East, Oceania and even Africa.

Philippines remittance flows continued to expand even during severe economic downturns such as the global financial crisis in 2008

This broad-based deployment forms a natural hedge against specific regional recessions in the past, with weak remittance flows from affected areas compensated by remittances from less affected parts of the world. The consistency of remittance flows has also been tagged to the altruistic nature of these transfers, with Filipinos sending home money to finance daily consumption, housing payments or tuition costs and reported to take on extra work just to make ends meet.

These factors were believed to be the reason why remittance flows continued to expand even during severe economic downturns such as the global financial crisis in 2008 or the Federal Reserve taper tantrum in 2013.

But Covid-19 has been a game changer

The Covid-19 pandemic has changed dynamics substantially, with the virus forcing economies around the world to implement strict lockdown measures to help mitigate the spread of infection. This development has undoubtedly threatened employment for scores of OFWs, with more than 230,000 Filipinos recently seeking aid from Philippine authorities as lockdowns were implemented across the globe.

We believe the initial figures reported by the government don't capture the full extent of OFW job losses, with many Filipino workers facing economic hardship in the coming quarters.

Slowdown in remittances to be widespread as lockdowns bite

Although remittances are sourced from almost every country (remittances from even North Korea hit $6m in 2019), the bulk of remittance flows are sourced from the top 11 host countries, all of which are facing at least a partial lockdown or border control measures. Lockdowns have grounded economies across the globe, resulting in widespread unemployment and contracting GDP.

The bulk of remittance flows are sourced from the top 11 host countries, all of which are facing at least a partial lockdown or border control measures

Oil exporters from the Middle East are top sources of remittances and, with crude prices currently subdued, we expect jobs prospects for the c.1.3 m OFWs in the region to be challenged even further. The United States, which is another big remittance provide recently reported more than 20m jobs losses for the month of April alone with OFWs likely joining the scores of unemployed.

Overall, economic projections for these countries are bleak and all are expected to be in recession this year, threatening job prospects for millions of OFWs based abroad.

Prospects for recovery don’t look good even after lockdown ends

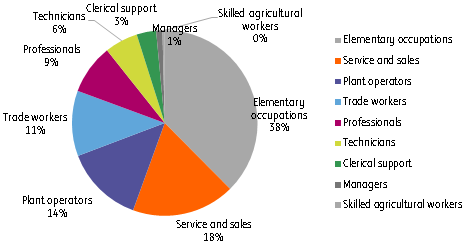

Meanwhile, job prospects for OFWs remain bleak even after lockdowns are lifted as the majority of OFWs are employed in sectors that are expected to struggle in a world of social distancing. Based on a survey conducted for registered OFWs, 37.6% of OFWs are employed in “elementary occupations”, which include domestic helpers and hotel/restaurant cleaning staff while 18% work in services and sales sectors.

This suggests that OFWs are likely to continue struggling to find employment as sectors such as hotel and restaurants take longer to recover quickly due to social distancing, leading to less remittance flows for OFWs based in these professions.

Given these dire prospects, we now expect OFW remittances to fall by up to 6.9% in 2020, the first contraction since 2001.

Remittances to contract 6.9% as job market remains challenged

The projected pullback in these once robust inflows spells likely economic hardship for recipients of OFW remittances.

Our current GDP forecast for 2020: -2.9%, factors in a drop off in consumption and investment activity as up to $2.1bn worth of remittances are lost due to the pandemic. On top of the economic impact of foregone remittances, the slowdown of these income transfers will also be reflected in the deterioration in the Philippines’ external position.

OFW employment per sector

PHP performance tied to current account balance

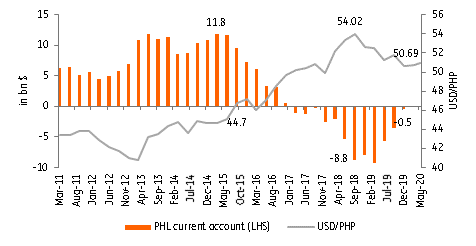

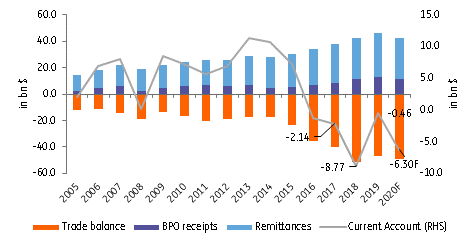

Over the last five years, remittance flows alongside trade in services (business process outsourcing receipts) grew at averages of 5.7% and 12.2%, supporting the current account by offsetting the chronic trade deficit.

However, in 2018 the current account deficit swelled to -$8.8bn, driven mainly by a surge in imports, forcing PHP to depreciate by 5.3% for the year. A year later, PHP would swing into appreciation, strengthening by 3.7% as the external position improved, with the current account deficit narrowing to -$460m.

Philippine current account balance and PHP

Without remittances, currency to weaken as deficit widens

Due to the pandemic, we expect remittance flows to contract by 6.9% in 2020, therefore we believe the current account is likely to be pushed deeper into deficit as remittances dip by c.$2.1 bn. In addition, we expect import demand to pick up substantially in the coming months as authorities seek to stimulate the economy by resuming large scale, import-intensive construction projects.

Given the projected sudden reversal in remittances and the government’s plans to resume import-intensive infrastructure programmes, we expect the current account deficit to widen substantially in 2020 to $6.3 bn from -$460m last year. The sudden swelling of the current account deficit will in turn force PHP back on its heels with the currency expected to weaken to 52.19 by the end of the year.

Given that job prospects for OFWs will remain constrained until the global economy heals, we expect current account woes to continue for the Philippines with the peso losing its footing after its recent outperformance in early 2020.

Philippine current account and components

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

20 May 2020

Good MornING Asia - 21 May 2020 This bundle contains 4 Articles