Philippines: how the pandemic impacted household savings and debt

We look at how the extended Covid-19 lockdowns and subsequent recession in the Philippines impacted households

Lockdowns impaired consumption

The Philippine economy is fueled mainly by household expenditure. Consumption accounts for roughly 72.8% of all economic activity and, given its sizable contribution, it's not a stretch to say that the Philippine economy will only go as far as consumption will take it.

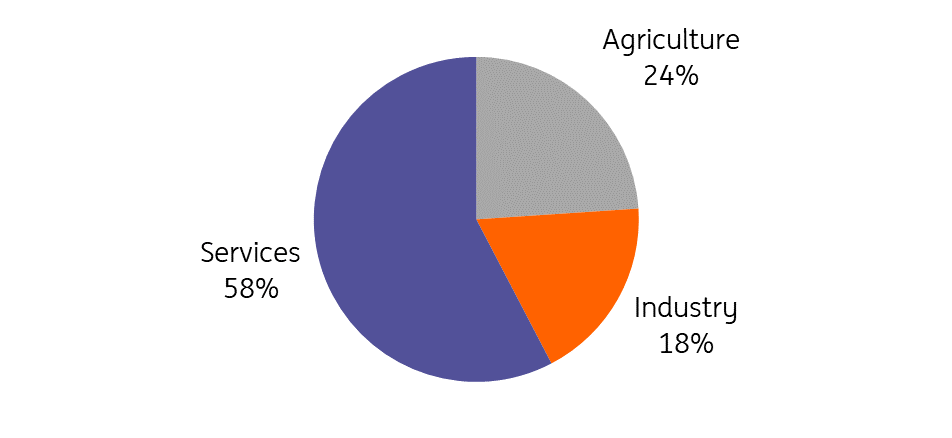

The Covid-19 lockdowns implemented from 2020 to early 2022 caused widespread unemployment, with the bulk of jobs in the services sector, which was largely unable to operate during that period. As a result, the Philippine economy entered a deep recession with households forced to seek aid from the national government, dip into savings, secure loans, or all of the above to make ends meet.

Just how did Filipino consumers get through the extended period of lockdowns? What changes were noted in spending and how were these financed? More importantly, will the effects of the pandemic impair consumption leaving households with high debt and low savings? We explore all of this below.

The Philippine labour market is dominated by the services sector

Back to basics, but trends are starting to change as economy reopens

With incomes constrained, Filipino consumption patterns changed. Spending was focused on the basics: food, shelter and in today’s economy, a reliable Wi-Fi connection to attend class or work from home.

Throughout most of the lockdowns, expenditure on food and non-alcoholic beverages (basic nourishment), utilities (with everyone stuck at home) and communication (to comply with social distancing guidelines) managed to stay positive. Spending on all other items, however, saw a sharp drop as Filipinos cut back on discretionary spending or were simply unable to do so because of mobility curbs.

Improvements in virus containment by the end of 2021 resulted in lower restrictions and the gradual reopening of the economy. As a result, so-called “revenge spending”, the outsized increase in expenditure after lockdowns, kicked in with households finally able to allocate spending on recreation, dining out and transport. Base effects helped magnify the recovery, but it appears that “revenge spending” remains very much in vogue even after removing the base effects. Expenditure on restaurants and hotels, recreation and culture and transport (partly due to air travel) recorded double-digit gains for five quarters and counting.

Low on savings

Limited access to income forced households to dip into their savings as expected and we see this trend across all three subsectors reported by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas’ Consumer Expectations survey. The drop-off in savings was most pronounced for the income bracket of Php10,000 to PHP29,000, even more so than the lower income group that earns Php10,000 or less per month. Lower-income households had access to government cash allowances during the lockdowns while households that did not receive cash aid were forced to dig deeper into their savings.

We note that despite the recent string of strong growth posted by the Philippines, households have yet to resume more normal savings behaviour, possibly as consumers still indulge in “revenge spending”. Households may opt to use reinstated income streams to pay down previous debt, which can be considered a form of saving. Thus, the pandemic and the recession that followed made households significantly less able to establish and maintain savings account balances during and even after the lockdowns.

Lockdowns and a recession has forced households to dip into savings

High on debt?

We know about the impact of lockdowns on savings but did the challenging job environment and economic recession force households to also increase their debt holdings? The short answer is no, as the percentage of households with savings fell during the pandemic. Actual data on savings levels per income group would help us get a clearer picture of actual savings levels and behaviour, however, such a metric is not readily available.

However, the data also shows that despite the drop in overall percentage, at least some households accessed salary-based loans and unsecured debt (credit cards) to cover expenses during a select period of the pandemic.

Tighter credit standards imposed by financial institutions may have contributed to lower bank lending, although the contraction may have also been driven by softer demand as firms and businesses put off expansion plans. The decline however was more pronounced for households based outside the capital region of Metro Manila compared to households in the city. Households based outside the capital region could have been challenged by mobility restrictions that limited access to bank branches inside the city.

The decline in consumer lending was traced to the drop in motor vehicle loans but salary-based loans and unsecured debt (credit cards) managed to show modest growth early in the pandemic. Loans of these types eventually declined as the lockdowns dragged on before finally reverting to growth after restrictions were gradually relaxed. According to the BSP’s consumer expectations survey, households used loan proceeds primarily for basic goods (56.1%), start-up/expansion (25.6%) and the payment of other debt (11.4%).

The lockdowns may have led to low savings levels across households but they did not necessarily saddle them with higher levels of debt. The percentage of households with a loan actually fell during the lockdowns perhaps due to tighter credit standards by banks, but also perhaps due to softer demand from households themselves.

Households took on less debt with decline pronounced in areas outside the capital Manila

Consumer lending weighed down by car loans

Have households been scarred by the pandemic? Yes and no

Did lockdowns leave households scarred with high levels of debt and lower savings? As income streams were challenged, households chose to draw down on savings to make ends meet and to a lesser extent accessed bank loans. The lockdowns and the recession that followed resulted in households with lower levels of savings but not necessarily higher levels of debt.

This new dynamic for households has implications for the Philippine growth outlook.

We believe that lower savings levels across households could eventually sap some momentum from overall consumption as households finally allocate a part of restored incomes to rebuild savings. Revenge spending has held sway so far (admittedly longer than we initially anticipated) but we believe the current inflation environment (6.3% year-on-year) should force households to cut back on spending and revert to more lockdown-style bare basics. Households in theory can resort to borrowing to finance additional expenditures, however, the rising interest rate environment could limit their options even if debt levels remain lower than pre-Covid norms.

Thus, we believe that the pandemic left households with low savings levels which will eventually work to dampen consumption and weigh on GDP given its sizable contribution to overall economic activity. We have lowered our full-year growth forecast to 6.1% with 2H growth slowing to 4.3% from 7.9% in the first half of the year.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article