Periphery in peril: Lockdowns, weaker safety nets and structural challenges pose grave risks to the recovery

The initial shock to the eurozone economy from the Covid-19 pandemic was very symmetric as all countries went into lockdown at roughly the same time. But the pace of recovery will be far more asymmetric, with many peripheral economies at risk of a longer lasting slump

A few factors drive potential recovery paths from this crisis

The single most important driver of the depth of the recession - the severity of the lockdown - was already evident in the first quarter growth figures. The more restrictive the lockdown, the deeper the contraction. In turn, the speed with which the lockdown measures are lifted should determine how quickly economies recover, though this is not the case entirely. In our view, there are multiple drivers that will play an important role in determining the path of recovery for countries, many of them relating to the lasting damage from the lockdowns. Some businesses will simply not survive the lockdown period. A rise in bankruptcies and unemployment will hamper the recovery, as the producing capacity of the economy has been hit and so too has demand, as people have lost their main source of income.

To get a sense of which countries are vulnerable to more lasting damage from lockdown periods, we look at multiple relevant factors:

- Depth and length of the lockdown

- Fiscal response including automatic stabilisers

- Sectoral and company size sensitivity to the corona crisis

- Financial position of the corporate sector

- Financial position of households

- Global value chain vulnerability

These factors all contribute to the pace of recovery and are likely to have a profound impact on how well economies bounce back from the historically sharp downturn. Which factors are most important depends on how the crisis continues to develop, meaning that it is still hard to tell which ones will be the most relevant. Many assumptions can be made, but we prefer to remain agnostic on this, as most factors point to similar conclusions anyway: the eurozone periphery will have the hardest time recovering quickly from this recession.

Most drivers of the speed of recovery favour the old “core” countries

Going over the factors mentioned above, a rather consistent picture emerges. There are very few scenarios imaginable in which southern eurozone economies manage to recover as quickly as their northern counterparts. Below we’ll list the drivers and differences between the North and South.

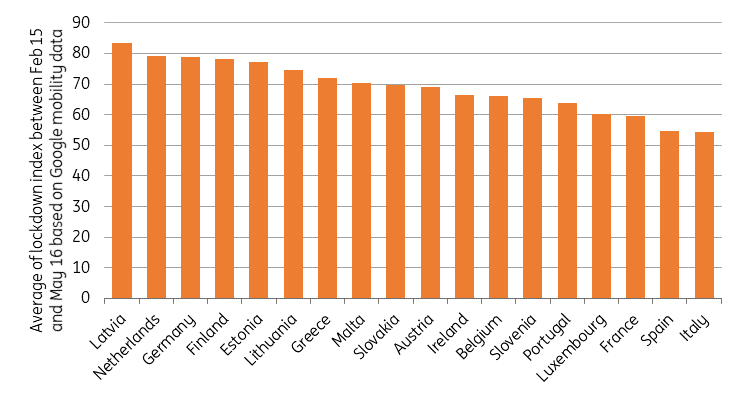

Length and depth of the lockdown is worst in most peripheral economies

The cumulative impact of the lockdown on the economy is largest in most southern economies. The first serious outbreak of the virus was in Lombardy, causing Italy to go into a hard lockdown. France and Spain followed the Italian example quickly, while the more northern economies experienced smaller outbreaks of the virus at first and opted for more lenient lockdowns. The depth of the lockdown proved to be the main driver of economic growth in the first quarter and is therefore strongly linked to the impact on activity. The longer it lasts and the more restrictive it is, the greater the chance of bankruptcies and higher unemployment, which are likely to make the recovery more difficult.

The lockdown impact has been largest in Italy, Spain and France

Chart 1 shows the average of our lockdown index for the period starting 15 Feb and ending 15 May. Over this period, the impact on the economy has been the largest in Italy, Spain and France, with Portugal also below average. Germany, Finland, Netherlands and the Baltics are all above average. As restrictive measures are now gradually easing, the countries with stricter measures still remain further away from normal daily life as we see from the latest activity data. This implies that the risks of more lasting damage to the economy continue to be more significant in Italy, Spain and France.

The countries with the stricter lockdowns have weaker fiscal responses and social safety nets in place

As stricter lockdowns cause larger economic harm, the countries that experienced them need more emergency government spending and would benefit from larger social safety nets to cushion the steep decline in economic activity. This has not been the case so far. While it is difficult to compare countries, there does not seem to be a clear correlation between the size of the emergency plans and how hard economies have been hit. In fact, in terms of direct fiscal spending announcements, the countries with looser lockdowns have announced the largest fiscal injections, at least so far.

The softer the lockdown, the higher the emergency government spending

There are also large differences in the safety nets that are in place for economic downturns. The automatic stabilisers of income are largest in Austria, Ireland and the Benelux and are weakest in Spain, Malta and the Baltics. A 100% shock to economic output translates to 62% drop in income in Germany but a 74% drop in Spain, according to the European Commission. The lower income retention during this period means less spending power during the recovery phase. That's a concern for countries with lower automatic stabilisers as they will experience a slower recovery, all else equal.

The structure of the economy matters

Some sectors have been harder hit than others by the corona crisis, so in order to gauge how quick the recovery will be, it's important to look at the sectoral composition of individual countries. To get a sense of how sectors have been affected by the crisis, we take the sectoral output loss estimates from the ECB Bulletin Issue 3/2020 and use the size of sectors within individual countries to estimate how vulnerable they are to their sectoral composition. Luxembourg, with a very large financial sector, is the least exposed to this specific shock followed by France and Finland. The Baltics, Slovenia and Austria are the most vulnerable.

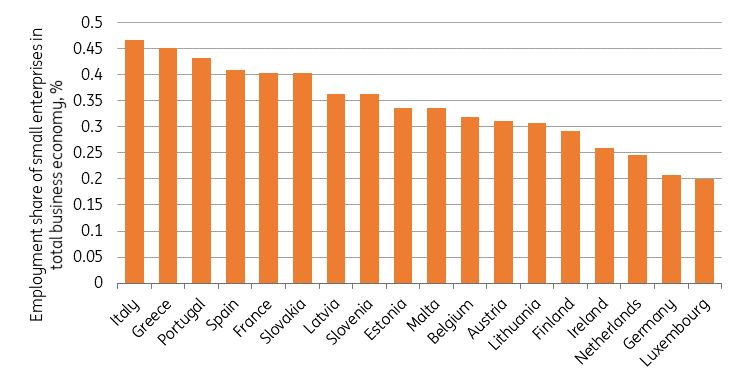

Southern eurozone economies rely more on small enterprises

It's not just sectors that matter but the size of companies, too. A larger share of small businesses in a country could increase the risk of more bankruptcies and therefore a weaker recovery. Roughly a third of total business employment in the eurozone comes from small businesses – under 10 employees – with large differences between countries. The share is 47% in Italy and just 21% in Germany, for example. Assuming that the more permanent damage to economies takes place in these small businesses, a higher share of employment could hamper the recovery.

The financial situation of corporates in some countries is more vulnerable than others

To bridge the period of lower or non-existent demand, companies obviously need to be in a sound financial position. Whether non-financial corporations had sufficient liquid buffers at the start of the lockdown to make it through the crisis is key. To get a sense of how vulnerable companies are to lower revenues over the course of the recovery, we can look at whether firms are net borrowers and what their liabilities are compared to their financial assets. The weaker the corporate sector, the longer it will take to recover from the lockdown period.

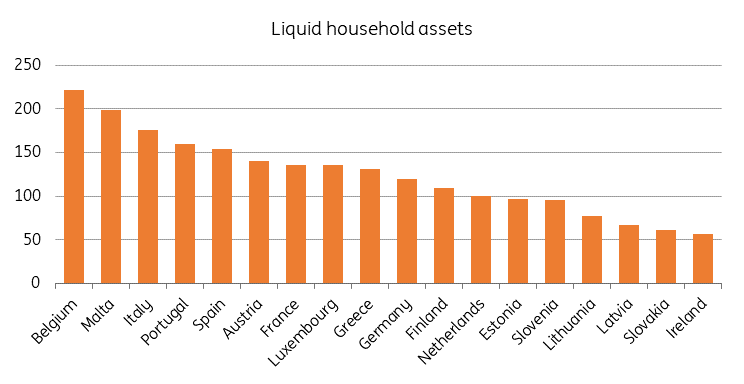

The same holds true for the liquidity of households. In countries with larger household buffers, consumer behaviour is less likely to be affected for a longer period of time, which means that a bounceback could happen more quickly. There are significant differences between countries here, with Belgium holding a particularly high amount of (semi-)liquid assets and the Central and Eastern European countries holding relatively little. This is also the case for the Netherlands and to some extent Germany and Finland, which could potentially hamper the recovery in the northern economies.

Northern eurozone households have relatively small liquid buffers

Open economies could be burdened in the aftermath

Being an open economy could be problematic to the recovery if foreign demand and/or production does not pick up quickly. More trade-dependent countries could be hit through supply chain problems, subdued exports if the main export destinations remain depressed for a longer period of time, and longer-lasting restrictive measures on trade. Countries like the Netherlands and Germany are more vulnerable to this recovery risk.

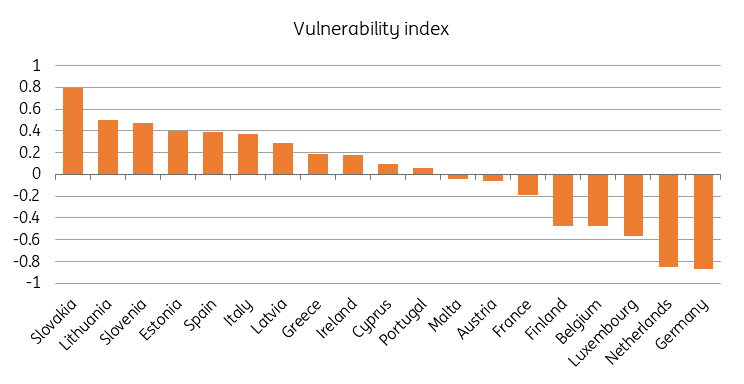

Old eurozone periphery is most vulnerable to prolonged slump

Taking all of these factors together, we can create an index measuring vulnerability to a prolonged coronavirus slump. Without applying any weights, the index is essentially agnostic about which factors are most significant. The countries that are most vulnerable, according to the index are those in Central and Eastern Europe, followed by Spain and Italy, while Portugal, Greece, Slovenia and Cyprus also rank as more vulnerable than average. The countries that are more likely to bounce back quickly are the northern eurozone economies. This sounds a lot like the old familiar lines drawn around the “core” and “periphery” of the euro crisis.

The “core” is better set up for a swift recovery than the “periphery”

A longer slump in southern eurozone economies could have worrying implications

If indeed southern eurozone economies are in for a much longer economic slump on the back of the Covid-19 crisis, this could have worrying implications from a debt perspective. While some countries have committed to smaller than average support packages, debt as a percentage of GDP will still be significantly higher if GDP does not recover for a longer period of time. It is not unthinkable that debt-to-GDP ratios rises faster by mid-2021 in countries that have spent a smaller share of GDP on the crisis, simply due to the diverging trends in economic growth.

Those higher debt levels could cause concern in the aftermath of the crisis. For now, the European Central Bank's Public Sector Purchase Programme and Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme form an effective backstop to any financial market turmoil related to concerns about specific eurozone countries, but whether that will remain the case longer-term is unclear. The ruling of the German Constitutional Court on the ECB's PSPP has cast doubt on a possible extension to the ECBs government bond buying, which could mean that euro break-up risk returns in 2021 if economic divergence increases again.

These concerns about debt levels already seem to have played a role in the size of the support packages by individual governments. The size of announced fiscal spending by country so far links best with market yields for government bonds and the level of government debt prior to the crisis, rather than the depth of the lockdown or automatic stabilisers, for example. This indicates that despite the historic steps taken within the EU, such as activating the “general escape clause” in the stability and growth pact by the European Commission and the ECB's PEPP bond buying programme, governments have still been wary about longer term debt worries while fighting this crisis.

The recent discussion and latest proposals on a European Recovery Fund indicate that there is a growing awareness of the longer-term problem an asymmetric recovery could create. A pan-European fiscal response on top of the already agreed package of European Investment Bank support, loans for short-time unemployment schemes and a possible European Stability Mechanism credit line, could alleviate this problem to a certain degree. This is particularly true if the fund uses grants rather than loans, though there could still be a potential problem with moral hazard. The message to financial markets concerned about debt sustainability and euro break-up risk would be loud and clear: the EU leaves no country behind.

Download

Download article

2 June 2020

The Covid-19 crisis: Finally, some good news This bundle contains 9 ArticlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more