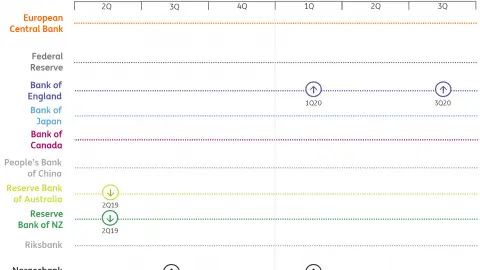

Our April guide to global central banks

Everything you need to know about central bank policy around the world over coming months

Our global central bank forecasts

Federal Reserve: Economy back from the brink?

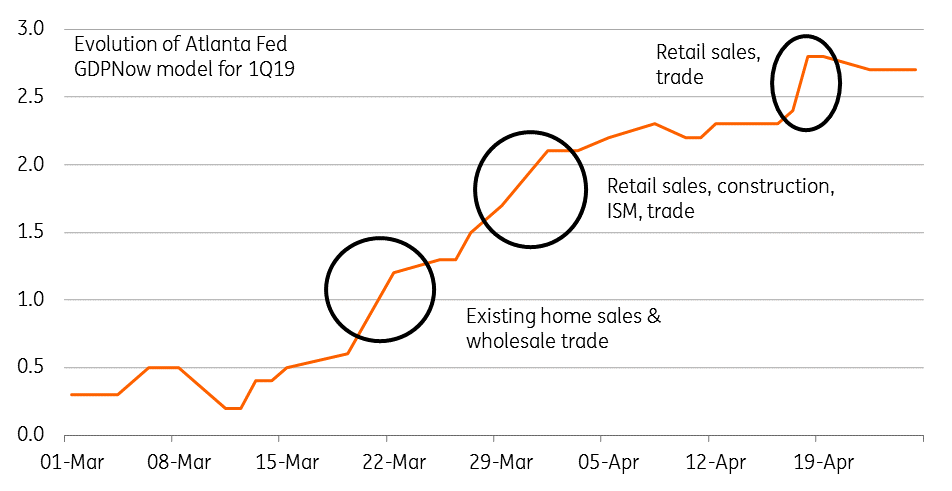

There was a lot of pessimism at the start of the year with the government shutdown, global slowdown fears and an inverted yield curve heightening talk of Federal Reserve interest rate cuts and a potential US recession. However, a recent run of firm macro data and a robust corporate earnings season have eased those fears.

Consumer spending is looking healthy, and there is the growing prospect of a US-China trade deal that can help lift some of the gloom and uncertainty hanging over the global economy. At the same time, the labour market looks resilient and wage growth is on an upward trend while the plunge in mortgage rates is helping to stimulate housing demand and construction spending is accelerating.

There are certainly more headwinds this year, but we continue to look for decent GDP growth in 2019 of 2.4%. We also expect inflation pressures to gradually build thanks to rising labour costs and improving corporate pricing power in an environment of firm demand. As such we see little reason for the Fed to cut interest rates this year with the market seemingly moving in our direction given the re-steepening of the yield curve.

The Atlanta Fed GDPNow estimate has staged a big turnaround

European Central Bank: Wait-and-see with a dovish tilt

They could if they would but they hope that they won’t.

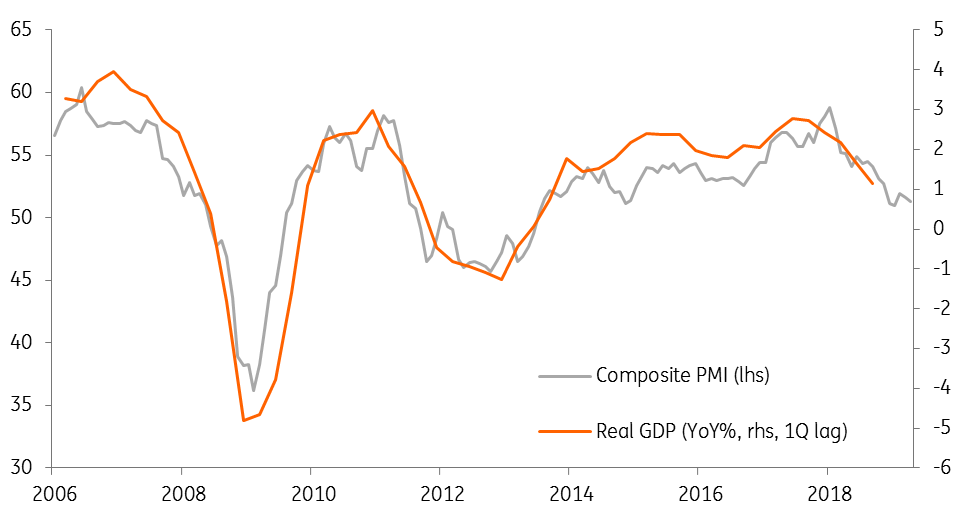

This is more or less the summary of the ECB’s current monetary policy stance. The unexpected slowdown of the eurozone economy, an unprecedented list of external risks and an inflation outlook far below target motivated the ECB to move towards an easing bias. At the last press conference, ECB president Mario Draghi tried to convey the message that the ECB stood ready to act to any further slowdown of the economy if needed. However, the ECB knows very well that its options for further easing are rather limited. In our view, the ECB will announce the technical details of the next round of TLTROs at the June meeting. The tiering system being discussed will only be an option if the growth outlook worsens further, as it would be the technical preparation for another cut in the deposit rate.

For the time being, the ECB is keeping its fingers crossed, hoping for stabilisation of the eurozone economy over the course of the year. This would mean no additional easing action. Even in such a scenario, any rate hikes are completely off the table. In its current set-up, the ECB has a clear easing bias. This, however, could change with the new ECB president, taking office in November. Until then, it is wait-and-see with a dovish tilt.

Eurozone PMIs have fallen

Bank of England: Brexit delay reduces chances of 2019 hike

While the Bank of England has kept the door ajar to further tightening, the chances of it happening this year have receded. The six-month Brexit delay means the threat of a ‘no deal’ Brexit has been postponed but will come back into focus as the new October deadline approaches. This looks set to keep a lid on growth, as firms maintain preparations for a possible cliff-edge scenario.

That said, skill shortages in the labour market have continued to drive wage growth higher. That means that if a Brexit deal can be approved by parliament, enabling the UK to leave the EU smoothly at some point over the next few months, then this could, in theory, bring a rate hike into sharper focus. But this is a big ‘if’, and in reality, we think it is more likely that no meaningful progress will be made before October. A rate hike this year is therefore not our base case, particularly amid the global shift to a more dovish central bank stance.

The latest Brexit timeline

Bank of Japan: Are there any easing options left?

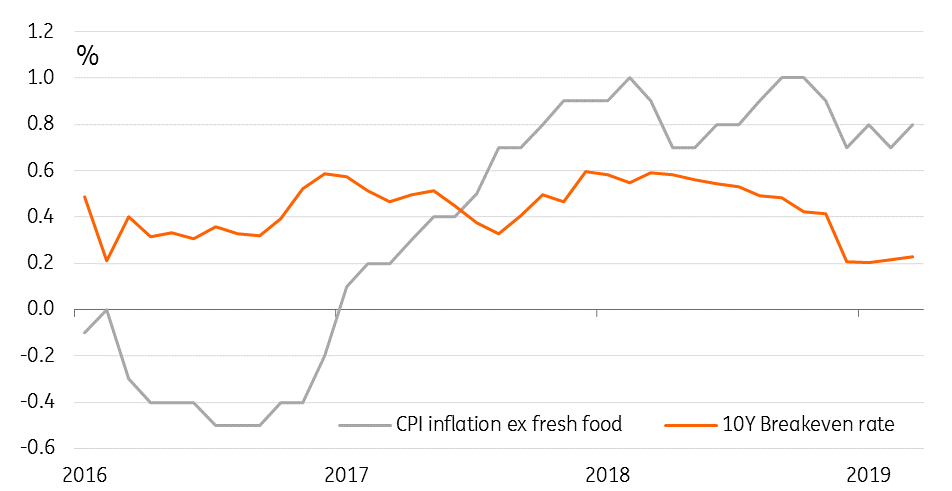

In the press conference of the latest BoJ meeting, Governor Haruhiko Kuroda admitted his frustration with the BoJ's inability to meet its 2% inflation goal. Along with this, came with an increasingly fierce pushback on what he was terming "Modern Monetary Theory" or MMT, which is shorthand for saying that ultra-low interest rates don't work. Tragically, we believe that there is more than a grain of truth in some of this critique of ultra-low rates. Kuroda's “gift” to the markets this time was to change the wording in the BoJ statement, which replaced "extended period" for describing how long low rates would be in place, to "around Spring 2020".

To paraphrase his explanation, he suggested markets were misinterpreting "extended period" and was anticipating rate hikes much sooner than was probable. This assessment by the Governor is, in our view, completely without substance. Not only does the market not believe that the BoJ will meet their inflation target over the BoJ's forecasting horizon, but an increasing number of market participants don't believe they will ever meet it (notwithstanding some slightly better Tokyo CPI figures for April). A tweak to forward guidance as delivered on this occasion is as meaningless as it is irrelevant, and markets shrugged it off as they should have done.

Japanese inflation is still well below 2%

People's Bank of China: Managing liquidity carefully

Strong credit growth (40% YoY) in the first quarter came as a big surprise to the market. After the release of credit data, the Chinese central bank (PBoC) has changed its policy tool from the required reserve ratio (RRR) to some more flexible liquidity management tools, including the medium liquidity facility (MLF), targeted MLF (that provides liquidity to smaller private firms) and seven-day open market operations.

We believe the central bank’s rationale behind not using RRR is that it’s one of the most rigid liquidity management tools. Once the RRR is cut, the liquidity injection is long-lasting, and the central bank can only absorb liquidity through open market operations, or by raising the RRR to unwind the impact.

The change of tools does not mean liquidity will be tighter, it just means the same amount of liquidity will be injected by different tools. We now expect no blanket RRR cuts in 2019, having previously forecasted three cuts. Targeted RRR cuts (for smaller firms) would only be needed if there is a series of bond defaults by private firms, which seems to be less likely given these firms can get loans from banks.

The central bank has been silent on using the 7-day policy interest rate. We believe that this tool has been shelved for now, given the central bank has stated that the interest rate transmission mechanism is incomplete.

USD/CNY continued to follow the ups and downs of the dollar index but not to the same extent. It was stable in the first quarter, and the yuan only depreciated 0.18% and fluctuated in a narrow range of around 1.8%. This narrow trading range could remain in place even after a trade deal has been reached.

China 7-day repo rate

Swiss National Bank: Negative rates set to remain the new norm

At the March meeting, the SNB maintained its ultra-loose monetary policy, keeping policy rates in negative territory and maintaining a willingness to continue intervening in the foreign exchange market if needed. The SNB has also reduced its conditional inflation forecast (which assumes an unchanged policy rate) and now expects an inflation rate of 0.3% in 2019 and 0.6% in 2020. This downward revision is the result of lower growth prospects in Switzerland, weaker inflation and a revision of expectations concerning global monetary policy. We believe that this downward revision is a sign that the SNB is more dovish than ever before, and does not plan monetary tightening over the forecast period.

The first interest rate increase will not, in our view, be considered before the next economic cycle begins. In the meantime, negative rates are likely to remain the norm for Switzerland.

The Swiss franc

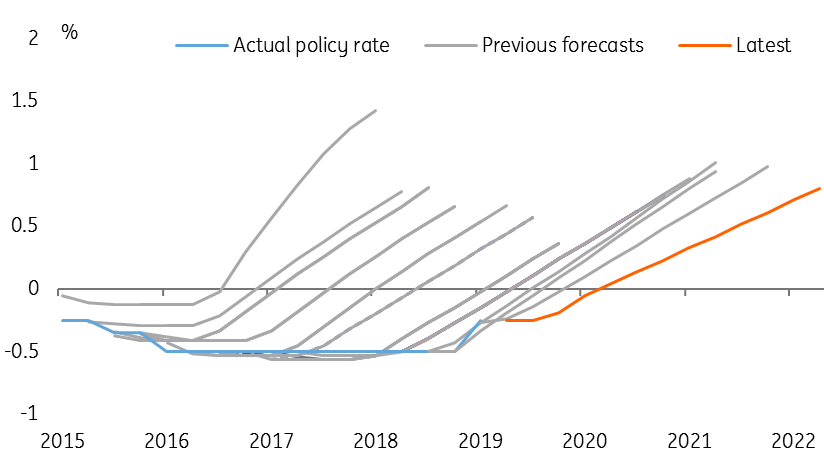

Riksbank: Another delay; more of the same to come

True to form, the Swedish central bank delivered yet another dovish surprise this week. A downward revision to its interest rate forecast pushed the expected date of the next rate hike into “the end of the year or at the beginning of next year” (i.e. 4Q19 or 1Q20) and also reduced the pace of tightening further out to just one hike per year in 2020-2022. In addition, the Riksbank announced a further SEK 45billion of QE ‘pre-reinvestments’ from mid-2019 to the end of 2020.

We expect more of the same later this year. The key factor for the Riksbank is continued anaemic inflation pressure, which looks unlikely to change in the near term. And with the major central banks on hold, we have a hard time seeing the Riksbank tightening policy at a time when the Swedish economy is slowing and looks set to underperform peer economies.

The Riksbank keeps delaying

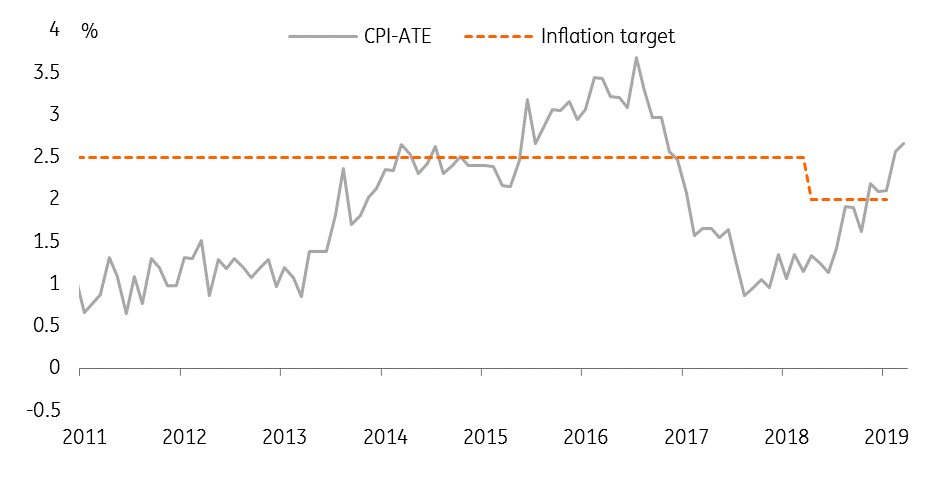

Norges Bank: Rising inflation pressure to keep central bank in hiking mode

In contrast to its Scandinavian neighbours, the Norwegian central bank has seen ample – and perhaps even excessive – inflation pressure this year. Core inflation in Norway has jumped to 2.5% and could well stay around that level this year as momentum in the domestic economy remains solid and wage growth is likely to increase further. While inflation is still comfortably within the NB’s +/- 1 percentage point tolerance band, strong price pressure means the central bank is likely to keep raising rates.

In addition to higher inflation, oil prices have risen further, boosting the energy-dependent Norwegian economy, and the Norwegian krone has remained weaker than the NB’s forecast. If this combination continues, that strengthens the case for higher rates in Norway, as higher oil prices stimulate both growth and inflation, while the exchange rate is not tightening financial conditions as much as the NB has anticipated.

We think the NB will hike at least once more this year and again early next year (at the September and March meetings). And if we see further upside surprises to inflation, or if oil prices rise further, those hikes could easily shift forward to June and December this year.

Norwegian inflation pushes higher

Bank of Canada: Tightening bias abandoned

The Bank of Canada has been taking a more dovish line for some time, but if there were any remaining hints of hawkishness, they were firmly abandoned at the April policy meeting. Interest rates were kept on hold at 1.75%, but more notably, the central bank removed its explicit reference to possible future rate hikes.

The labour markets underlying strength has been one of the only bright spots in the economy, but if the Bank of Canada’s (BoC’s) spring Business Outlook Survey is anything to go by, the positive news we’ve been getting from employment reports could slowly start to fade. Even though labour-related production constraints remain the most frequently cited bottleneck, the indicators of labour shortages fell. This could suggest labour market pressures are beginning to subside.

Overall, policymakers will focus on three things: global trade uncertainty, the weaker outlook for the energy sector and doubt surrounding household activity. We think there is scope for some upbeat news as we enter the second half of the year - reinforced by the fact that the Bank still describes its current stance as “accommodative”, suggesting that the committee are less convinced than the market that rate cuts are on the horizon. Nevertheless, we aren’t expecting a rate hike this year.

Bank of Canada Business Outlook Survey suggests jobs market weakness ahead

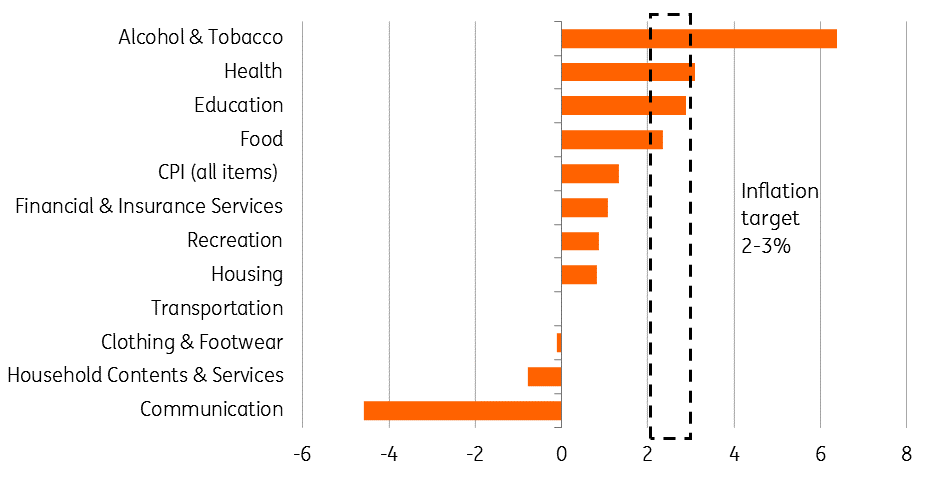

Reserve Bank of Australia: Weaker inflation raises chances of a rate cut

The latest set of RBA minutes discussed the case for a rate cut. But even though the conclusion was that there was no strong case for an imminent cut, markets aren’t convinced, and neither are we.

Data initially supported the “on hold” view, with full-time jobs in March rising by more than 48,000, reversing the previous month’s weakness, though this may have come at the expense of some temporary jobs (not necessarily a bad thing). A rising unemployment rate can also be put down to greater labour market participation (also probably not a sign of desperation).

But more recent inflation data was a huge disappointment, and at 1.3% in 1Q19, down from 1.8% in 4Q18, seem far too dismal for the RBA to ignore. Indeed, these inflation numbers are so bad, that a cut at the 7 May meeting can’t be totally ruled out.

Forecasters and the market had been converging on an August rate cut, just after the next CPI reading. But waiting this long against this backdrop seems completely unnecessary.

Australian inflation components

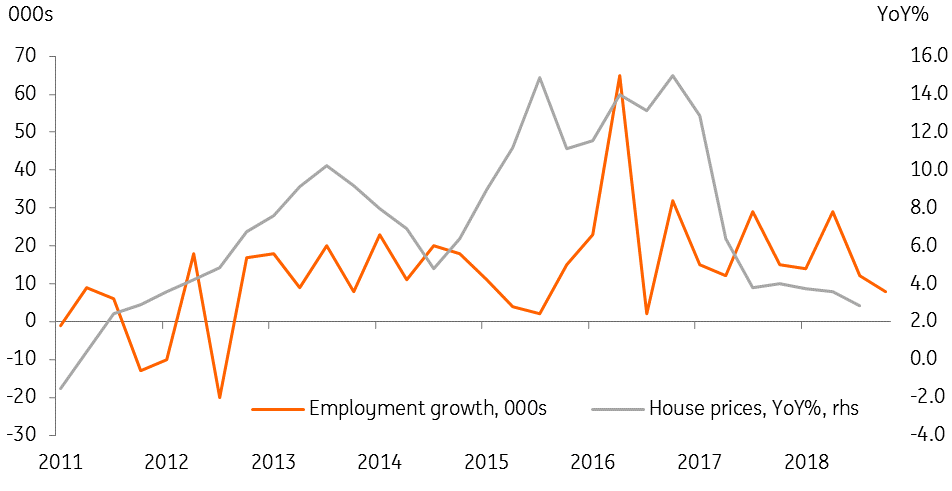

Reserve Bank of New Zealand: A rate cut looks increasingly likely

Further inflation weakness in New Zealand also puts the 'on-hold' RBNZ view at considerable risk, and without the same labour-market strength that was helping to keep thoughts of the RBA on hold alive (until their inflation data snuffed out this idea).

The next RBNZ meeting on 8 May will come just a week after 1Q19 employment data (and the day after the RBA) and with no expectation that the labour market will do enough to provide reassurance that a balance between low inflation and decent growth is being achieved, a cut on 8 May looks increasingly likely.

The balancing factor here is house prices, which are in a healthier position than they are in Australia, but they are still growing more slowly, and are sufficiently soft that they won’t change the picture even if they hold at the March 19 growth rate of 2.6%YoY.

Market OIS futures put the probability of a cut at the next meeting at 61.7% now, which is up to a level that makes it hard for the RBNZ to ignore.

New Zealand house prices vs. employment

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

26 April 2019

What’s happening in Australia and around the world? This bundle contains 9 Articles