Our answers to your global economy questions

What would it take for the Fed not to cut this year? And can Europe really diverge from the US on interest rates? Our economists offer their answers

What would it take for the Fed not to cut at all this year?

Having signalled the potential for three interest rate cuts this year as recently as March, officials have moved to downplay the possibility of imminent policy easing. Three consecutive 0.4% month-on-month core inflation prints, ongoing strong consumer spending numbers and a tight jobs market have given officials little option but to suggest that interest rates could stay higher for longer to ensure inflation returns to target.

We believe talk of a second wave of high inflation is misplaced. To generate a renewed, sustained acceleration we would need to see the re-emergence of wage pressures – which put up business costs that are then passed onto the consumer. However, the plunging quits rate and declining hiring intentions surveys suggest a cooling is more likely. Moreover, the Atlanta Fed’s wage tracker is returning to pre-pandemic rates as is Indeed’s own data on salaries of new job postings on its widely used job listing website. That said, if we are wrong and we do see business surveys rebound, hiring intentions pick up and unemployment start to move lower again, then fears of a protracted period of sticky inflation would keep the Fed policy rate elevated.

Another assumption has been that housing rents slow in line with market measures of private sector rents. Should we see a re-acceleration in rents this would be a major problem for the Fed given it is by far the largest component within CPI index.

Furthermore, if inflation does stay sticky for a few more months and we see growing momentum behind President Trump’s re-election campaign this could make the Fed wary of easing at all this year. Proposals for tax cuts that shore up domestic demand, immigration controls (which limit labour supply and potentially boost wage pressures over the medium term) and tariff hikes that may add to inflation pressures, could result in expectations of potential interest rate increases in 2025.

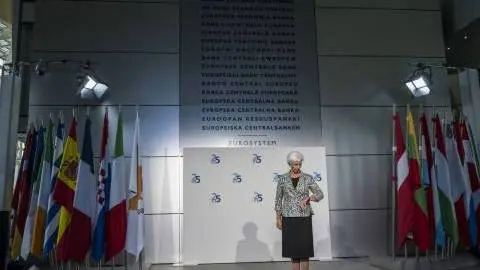

Can central banks in Europe really diverge from the Fed?

A year or two ago, central banks across Europe were chasing US rates higher as inflation data proved ever more shocking. Now, the situation is more nuanced. The likes of Switzerland and Sweden have now cut rates despite the Fed turning more hawkish, and the Bank of England and European Central Bank are signalling they can still cut rates this side of summer. With inflation closer to target – and also proving a bit more predictable – central banks in Europe seem more comfortable with diverging from the Fed. They also seem less acutely concerned about the risk of currency weakness.

However, we think this divergence has its limits. Already at the ECB, we detect a change in mood amongst some officials, where there are fears that recent US inflation stickiness could be mirrored in Europe later this year. The risk of a “reverse Trichet moment” – a reference to the two infamous 2011 rate hikes that were quickly reversed – whereby the ECB is forced to curtail a fledgling easing cycle appears to be worrying some of the hawks.

The first ECB and - to a lesser extent - BoE rate cut seems relatively baked in by the summer. But a scenario where the Fed only cuts once – or not at all – this year would, we think, inevitably see the likes of the ECB and Bank of England scale back their easing ambitions later this year. This is partly why central banks in Europe are signalling they aren’t inclined to cut at every consecutive meeting.

What would higher oil prices mean for central bank rate cuts?

While we only expect moderate strength in oil prices from current levels, several scenarios could see prices trading significantly higher. A key upside risk to the oil market would be if OPEC+ overtightened the oil market during the second half of the year. Currently, we expect the market to be in small surplus over the latter part of the year, requiring only a partial rollover of current supply cuts, but if members rollover the full 2.2m b/d of cuts for the remainder of the year, it leaves the potential for Brent to trade towards mid- $90/bbl, assuming oil demand does not disappoint. An even more bullish scenario is if tensions in the Middle East reignite again, leading to actual oil supply disruptions. While significant spare OPEC production capacity would be able to cushion the market in the event of most supply disruptions, an extreme scenario where it would not help, is if oil flows from the Persian Gulf (through the Strait of Hormuz) were disrupted. This could put as much as 20m b/d of oil supply at risk, which if lost, could push oil prices well above $150/bbl and towards $200/bbl.

When oil prices surged after the pandemic, and latterly with the war in Ukraine, the direct impact on gasoline added roughly 1.5 percentage points to US headline inflation. The impact was a little lower in Europe, given that tax makes up a greater share of the consumer price, and the weight in the inflation basket is lower than in the US too. Back then, in year-on-year terms, oil prices were increasing by 100% at times. That suggests to get a similar shock this time around we’d need to see oil prices up around $150/bbl. Still, with the “last mile” proving a headache for central bankers, especially in the US, more modest increases in oil prices could still be a headache – and remember those impacts cited earlier don’t include so-called second-round effects (eg transportation costs) on other goods.

Earlier this year, the ECB tried to play down the impact of potentially higher oil prices on its monetary policy by stressing that the impact on inflation could differ and would also depend on the strength of the economy. Still, according to standard models, a 10% increase in oil prices would potentially push up inflation by 0.1 to 0.2 percentage points over the next two years. An oil price spike could therefore limit the ECB's room for rate cuts in 2025, unless of course higher oil prices were to also hit the fragile eurozone recovery.

Similar to the eurozone, significantly higher energy prices would be a constraint on US economic activity as this erodes household spending power and there is a more direct transmission into the retail price of gasoline due to lower taxes versus Europe. The US is a net energy producer, so this will provide some mitigation for economic activity, but given consumer spending is 70% of the economy the overall effect will be a drag on growth. The inflation impact comes via direct fuel prices as well as transportation and logistics pricing. How the Fed responds is a little more complex than in Europe given the Fed’s dual mandate of 2% inflation and maximum employment – which could be impacted by the damage to growth from higher energy costs. On balance, it would likely make the Fed more wary of implementing significant interest rate cuts.

What could force central banks to cut rates more rapidly than currently expected?

In the past, rate cutting cycles by major central banks were normally triggered by either a recession and/or a severe (financial) crisis. Think of the financial crisis, the euro crisis or the pandemic; just to look at the last 15 years. While a recession in the US, despite the current resilience, cannot be excluded, the ECB would probably react to a new escalation of the war in Ukraine with more aggressive rate cuts. Also, as discussed in the last Monthly Update, the US presidential elections could bring new economic policies in the US, which eventually would harm the eurozone economy, and would eventually force the ECB to cut rates more aggressively.

In the case of the US, the Federal Reserve has more flexibility to respond to economic stress given its dual mandate. Therefore we don’t necessarily need to have inflation especially close to target for the Fed to take action if it believes there are brewing problems in the labour market that will eventually provide downside risk for inflation.

The case in point is the weakness in labour hiring surveys. The ISM employment components are at levels historically consistent with payrolls falling by more than 100,000 per month. The NIFB survey is at levels historically consistent with private payrolls growth of 0-50,000 by the summer, while the plunge in the quits rate, indicating workers are increasingly nervous about job security, is at levels historically consistent with the unemployment rate rising to 5%. Should these occur we strongly suspect the Fed will be inclined to signal a series of interest rate cuts are on the way.

If this is then compounded by re-emerging issues in the small banking sector of the US, resulting from the realisation of loan losses relating to commercial real estate and consumer loans, then the Fed may also feel the need to step in pre-emptively to mitigate any stress in the financial system. Such stress would inevitable tighten credit conditions in the economy and the Fed may feel the need to offer support via policy rate cuts.

Then there is inflation itself. Insurance and medical premiums plus sticky rents are the main causes of the firmer-than-expected 0.4% core CPI prints through the first three months of the year. This was also the situation last year until core inflation cooled in subsequent months. This has given rise to talk of “residual seasonality” – essentially seasonal adjustment factors have not fully adjusted for when premiums for insurance are adjusted each year. Given the 20%+ increase in some insurance costs, this is a potentially meaningful situation. Residual seasonality is a debated topic and there are no guarantees, but if we do indeed see a repeat of 2023 this would give the Fed more room to ease monetary policy in the latter part of the year.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

9 May 2024

ING Monthly: I wanna dance with somebody This bundle contains 14 Articles