Malaysia macro update – It’s downtime

First the political jitters, then the pandemic and related controls on movement and then an oil price crash – all have borne down on the Malaysian economy, setting this year up to be the worst since the 1998 Asian financial crisis

Key takeaways

Covid-19: The outbreak is one of the less severe in Asia and the recovery rate is among the highest in the region. But the infection curve is yet to flatten, while the prospect of a surge in infections among migrant workers is looming large.

Growth: With the key economic drivers of trade, tourism, and oil taking a beating from Covid-19, 2020 will be the worst year for growth since the 1998 Asian financial crisis. We expect GDP to fall by more than 8% in 2Q and by about 4% for the entire year.

Inflation: High unemployment and weak spending should keep CPI inflation on a steady downward path, prompting a further cut to our 2020 forecast to -2.5% from -1.0%.

External sector: Weak global demand, low commodity prices, reduced prospects of an electronics upturn, and halted tourism are likely to move the current account surplus down.

Policy stimulus: Tight public finances constrain any fiscal stimulus, though about 3% of GDP real fiscal thrust isn’t at all bad. Falling inflation and high real interest rates call for more central bank policy rate cuts. We expect an additional 100 basis point cut in this cycle.

Post-Covid recovery: We look for a deeper downturn to be followed by a prolonged recovery. Permanent demand destruction in some sectors could force potential growth lower. We see 3-4% as the new normal for GDP growth.

Politics: The last thing the economy and the financial markets need is another bout of political risk. The current fragile coalition could offer such a risk, suggesting the MYR will remain an underperfomer in Asia throughout the rest of the year.

It's downtime!

Covid-19 – curve is yet to flatten

The total number of Covid-19 infections as of 25 May stood at 7,417 with 115 deaths. This puts Malaysia among the Asian countries not so badly affected by the crisis so far. Of the total, 81% of cases are recovered, a relatively better recovery rate compared with some of the worst affected Southeast Asian neighbours (Singapore 46%, Indonesia 25%, Philippines 23%).

The faster recovery may be attributed to early containment measures. Malaysia was among the first Asian countries to put in place a nationwide movement control order (MCO) on 18 March. Initially started for two weeks the MCO was extended four times with the latest extension to 9 June, albeit with some relaxation recently. As the strain showed signs of abating the authorities decided to ease restrictions starting 4 May and allowed some industries such as manufacturing and construction to resume operations at their normal capacity.

We won’t call it over nonetheless. The relaxed movement restrictions coupled with the continued rise in new infections sustain the risk of a second wave. The daily new infections so far in May have averaged at 56. This compares with 630 average in neighbouring Singapore, though the number here is skewed by the rapid rate of infections among migrant workers. As in Singapore, the threat of a surge in infections among this group in Malaysia is on the rise. Most of them are illegal migrants and refugees from neighbouring countries, packed into large dormitories.

The government has already begun a crackdown of illegal migrants and detaining and testing this entire community. The biggest single-day spike in infections in more than a month over the last two days -- by 172 on 25 May and 187 on 26 May, most of which were migrants in detentions centres, reinforces the persistent Covid-19 risk.

Covid-19 spread

| 0.7% |

1Q20 GDP growthYear-on-year |

| Higher than expected | |

The economy is battered - growth

GDP growth remained in positive territory in 1Q20. A 0.7% rise over a year was a better outcome than the consensus of a 1% fall, and it also compares with steeper GDP declines elsewhere in the region. Yet it was a sharp dip from 3.6% YoY growth in 4Q19, and the slowest quarterly growth in over a decade, since the 1.1% fall in 3Q09 induced by the global financial crisis. Moreover, a 2% quarter-on-quarter (seasonally adjusted) GDP fall set the economy on the path of a recession, probably deeper than during the GFC.

A better 1Q GDP performance comes against an adverse economic and political backdrop. First, the political turmoil leading to the end of the Mahathir government in late February depressed economic confidence. Just as the Muhyiddin administration assumed power, it was forced to implement the Covid-19 lockdown in mid-March, bringing the economy to a near-standstill state. As if all this wasn’t enough, a crash in the global oil price in March made matters worse for this net oil-exporter country.

Even so, manufacturing growth held in positive territory, albeit a slowdown to 1.5% YoY from 3.0% in the previous quarter. Agriculture and construction were badly hit with -8.7% and -7.9% YoY growth, while services growth halved to 3.1% from the previous quarter.

Private consumption remained the spending side GDP driver with a 3.9 percentage point contribution to headline growth, though smaller than 4.5ppt in 4Q19. Government consumption helped with another 0.6ppt (we doubt it was due to stimulus). Exports of goods and services turned out to be the bigger drag, shaving off 4.7ppt from GDP growth, but it was mainly due to weak services rather than goods exports. Imports subtracted 1.4ppt from GDP growth and the fixed capital formation got it down by another 1.1 ppt.

Sources of GDP growth

The economy is battered - other indicators

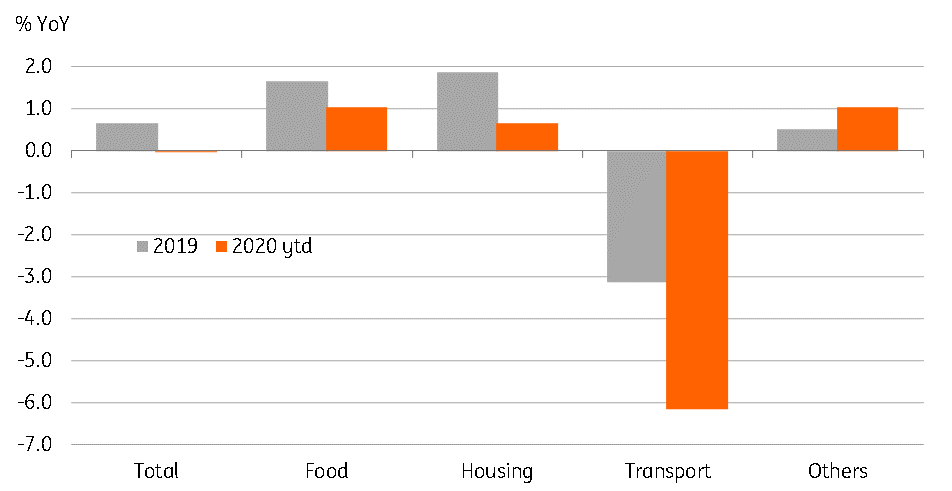

Among other economic indicators, CPI inflation posted the steepest fall in April since the GFC to -2.9% YoY. Lower food, housing and transport prices were responsible. The year-to-date inflation was zero, down from 0.7% in 2019.

The customs-basis goods trade was relatively firm. Exports eked out a 1.1% YoY rise in 1Q, while imports posted a mild drop by 2.6% and the cumulative trade surplus of MYR 37 billion was little changed from a year ago. Despite downward price pressure, oil and gas exports advanced 10% on the year. And, after an outperformance in 2019, electrical and electronics exports have been a weak spot, with an 8% fall in the first three months. The demand in key trade partners also held up well despite the Covid-19 outbreak. Shipments to the US rose 9.5% in 1Q, those to Japan were flat, and to China were down only 1.3% on the year. An outlier 14% fall in exports to Europe, the worst-affected region by the pandemic so far, provides a sense of what to expect about demand from the rest of the world with intensified disease spread in this quarter.

A strong merchandise trade surplus was supportive of the current account surplus, but not enough to mitigate outflows on the services side. The result was a sharp dent to the current account to MYR 9.5 billion from MYR 17 billion a year ago, pushing the ringgit to be among Asia’s weakest currencies with an over 6% year-to-date depreciation against the USD.

CPI inflation - key components

More pain ahead - trade, tourism, oil

The economic data released so far doesn’t capture the full impact of Covid-19, which will mainly impact the current quarter due to the movement control orders in place for much of this quarter. Although the restrictions have started to ease from early May, the broader control measures continue until 9 June. The extended lockdown means a virtually entire quarter of significantly sub-normal economic activity. The impact stands to be compounded by similar restrictions in the rest of the world, depressing the outlook for an economy heavily dependent on trade, tourism, and commodities.

The Covid-19 situation in all major trade partners – the US, Europe, China and Japan together absorbing 40% of total exports, has been bad. The same is true about the rest of Asia, the destination for almost half of Malaysia’s exports. Besides weak global demand, the domestic supply chain disruptions caused by movement restrictions will be an ongoing overhang, making this a year of exceptionally weak trade flows – not just for Malaysia but for the rest of the world as well.

Malaysia is the second-most favourite tourist destination in Asia after Thailand. About 26 million visitors annually, nearly 90% of whom are from within Asia, bring over MYR 86 billion in revenue (5.7% of GDP). The disease has brought the sector to a standstill. Even as cross-border travel resumes after the outbreak, tourists are unlikely to flock back to their favourite destinations. Some permanent demand loss for the sector may not be an overstatement in the post-Covid era.

The supply glut in the global oil market and nosediving prices add to the pain of already weak oil and gas exports (make up for about 13% of total exports). Having briefly turned negative in April, WTI has bounced back quickly above $30/barrel, thanks to production cuts by major oil producers and the gradual opening of economies bringing back some demand. Still, a significant loss of demand in the transport sector globally will be a strong headwind for a return to what we view as the optimal level for crude oil price (in the $55-65/barrel range in recent years) anytime soon. It will need a complete normalisation of the situation after Covid-19, something hard to imagine in the rest of the year and well beyond. However, as the new normal we could imagine some permanent loss of demand (for example, a new normal of ‘work from home’ depressing demand for transport).

Exports and tourism by main destinations

Sufficiently loose fiscal policy

The new government spared no time in rolling out a sizable stimulus, equivalent to about 17% through three packages since late February (including the first MYR 20 billion package by Mahathir Mohamad just days before he was ousted). However, this largely included monetary support via easier credits, loan moratoriums, and bank guarantees, etc. which don't qualify as real spending, nor do measures like early withdrawals of retirement savings and deferrals of employer contributions to these schemes.

Leaving all the monetary measures out, we estimate a real fiscal thrust of only 3.3% of GDP. This is still not bad given the already tight fiscal position. While the extra-budgetary spending should nearly double the fiscal deficit this year from the 3.2% of GDP target in the original budget (announced in October 2019 by the previous government), the revised fiscal deficit estimate of 4.7% from finance minister Zafrul Azis was a further letdown, indicating much lower real stimulus.

It is not only the extra spending that will swell the fiscal deficit. Government revenue is also poised for a hit from weak growth as well as slumping oil revenue. Even as Malaysia has diversified away from the petroleum sector over the last few years, tax and royalties from state-owned companies in the sector still make up 10% of total government revenue. The local industry body estimates that a US$1 change in Brent price causes MYR 300 million change in the government’s revenue. Of course, there will be some saving in spending on fuel subsidies, but on balance it’s going to be negative.

We expect the fiscal deficit this year to be well above 6% of GDP. It is what is needed right now, even if it wipes out all the consolidation in public finances since 2009.

Stimulus - where the money is going?

A decade high fiscal deficit

Monetary easing follows suit

Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM), the central bank, has also accelerated its monetary easing with a 50 basis point cut to the overnight policy rate (OPR) to 2.00% at its last meeting on 5 May. This followed two 25bp cuts in the first two meetings of the year in January (this was not really Covid-related) and in March. The BNM also lowered banks’ Statutory Reserve Requirement (SRR) by 100bp to 2.0% on 19 March, releasing MYR 46 billion into the banking system. The aggregate liquidity support so far, including repo operations and outright purchases of government securities, comes to MYR 58 billion or 3.8% of GDP.

While already stretched public finances limit the scope for more fiscal stimulus, falling inflation is making more room for BNM monetary easing. The BNM doesn’t particularly target inflation in setting monetary policy. But the economy, staring at a deep downturn ahead, is demanding more policy accommodation. Cutting interest rates remains an important option at the central bank’s disposal, while there is space to do so.

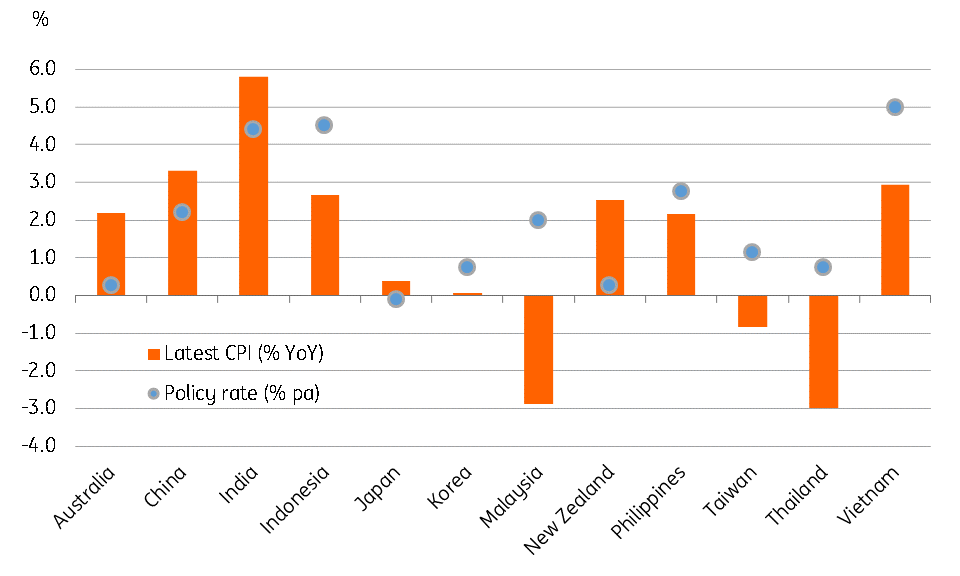

The current 2% OPR against a -3% CPI inflation implies a real interest rate of 5.0%, the highest among Asian countries. We don’t see any reason why the policy rate couldn’t fall further. We expect another 100bp cut in this cycle, to be delivered over the next two scheduled meetings in July and September and taking the OPR to an all-time low of 1.00%.

Highest real interest rate in Asia

Lingering political risk

Events in February demonstrated persistently uncertain Malaysian politics (see: Has Malaysia’s political standoff really ended?). The fall of one fragile coalition government of Dr Mahathir Mohamad gave way to another shaky one of Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin.

With the King’s approval and backing from the formerly dominant UMNO party (United Malays National Organisation), Muhyiddin grabbed power on 1 March. The pandemic gave him breathing space to prove his majority in parliament, but the outbreak also put to the test the ability of the fledgling administration to handle the unprecedented crisis. The speedy implementation of measures to combat the disease and support measures to avert the economic fallout deserve some credit. However, these don’t guarantee lasting power for the ruling administration.

The issue of the legitimacy of the new government is still hanging in the balance. So is the sword of a no-confidence motion hanging over Muhyiddin, given the long-time rival-turned-allies, Mahathir Mohamad and Anwar Ibrahim, are driven to regain the popular mandate they won in the general election two years ago.

The ruling administration needs 112 seats in the 222 member parliament to remain in power. With its undeclared slim majority at risk of aggressive horse-trading, anything could happen if the no-confidence vote eventually takes place. The failure of the new government to prove its strength in parliament could mean a snap election on the horizon, before the next scheduled general election in 2023. Such a political turn could be more painful for the financial markets than the pandemic.

Parliament had its single-day sitting on 18 May, the first since the Muhyiddin administration came to power. There was no political business aside from the King’s speech, which was carried out on the pretext of Covid-19 infection risk. The next parliament sitting won’t be until July, when we might have some more clarity about the fate of the current government.

We believe political uncertainty is far from over and it could be an ongoing threat to the economic recovery post-Covid-19.

Painfully slow post-Covid recovery

The entire world is bracing for the worst economic recession in decades. Malaysia is no exception despite the economy’s relatively resilient performance so far this year. We remain sceptical that aggressive fiscal and monetary stimulus will be effective in arresting the economic slump until confidence returns, which won't be until the outbreak ends.

As such, 2020 is shaping up to be the worst year for the economy since the 1998 Asian crisis. We anticipate an over 8% YoY GDP fall in 2Q and 3.9% fall in the entire year. As elsewhere in the world, the recovery from such a deep slump is going to be lacklustre, with growth probably never returning to its 5-6% potential. Instead, permanent demand destruction in some sectors raises the prospect of the growth potential nudging down to what we see as a new normal of 3-4%. Our GDP growth forecast for 2021 remains at 3.6%.

We forecast CPI inflation this year falling to -2.5% as low commodity prices and weak demand keep prices on a downward trend. We should see a return to positive inflation in 2021, though it’s still going to be anaemic, at our 0.8% forecast for next year.

Lower commodity prices coupled with weak exports and tourism mean a continued narrowing of the current account surplus. We expect a sharp fall in the current surplus from 3.4% of GDP in 2019 to 1.5% of GDP, followed by a modest pick up to 1.9% in 2021. Meanwhile, weak investor sentiment will remain a strain on capital inflows and the overall balance of payments, resulting in some reserve losses.

Negative sovereign actions drawn from deteriorating public finances will be an added drag on investor confidence. Moody’s and S&P have so far maintained ‘Stable’ outlooks on their ‘A3/A-‘ ratings of Malaysian sovereign debt, but Fitch Ratings recently cut its ‘A-‘ rating outlook to ‘Negative’ from ‘Stable’. Unfortunately, it’s hard to justify such negative actions in these bad times when economies require aggressive policy support. That said, exceptionally weak public finances and rising public sector debt are unlikely to fade from being an overhang on external creditworthiness for the next couple of years. We expect the government budget deficit to widen to 6.3% of GDP in 2020, nearly double the 3.4% gap in the last year. With anaemic growth, fiscal consolidation will remain a painfully slow process over the coming years. We do pencil in some narrowing in the deficit below 5% next year.

The last thing the Malaysian economy and financial markets need is another bout of political anxiety. We think the markets have taken in their stride the dismal state of the economy in the near-term due to the global health crisis. But, in such a weak economic backdrop, renewed political jitters could prove to be a highly significant dent to investor sentiment in our view. As noted earlier, we won’t discount such political risk on the horizon and local financial assets succumbing to increased selling pressure as a result.

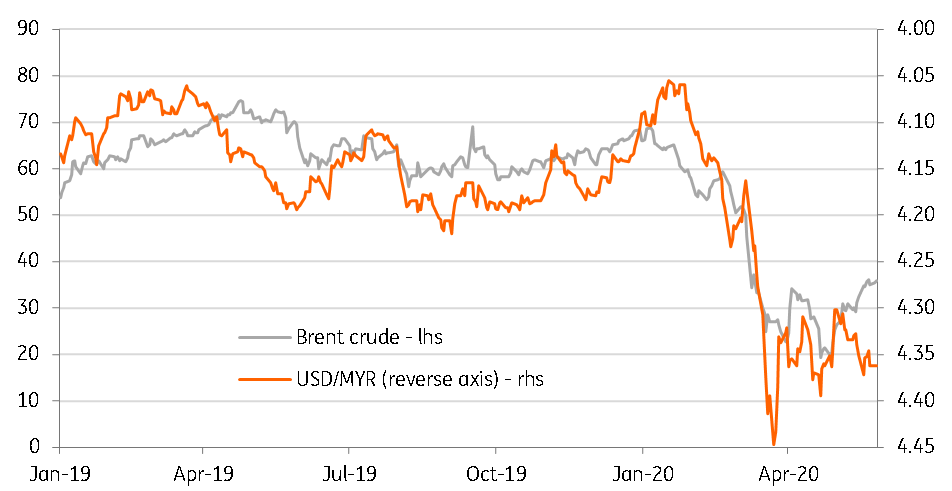

Uncertain politics and an adverse terms of trade shock from weak commodity prices should keep the MYR as an Asian underperformer in the rest of the year. Our end-2020 USD/MYR forecast is 4.35 (spot rate 4.36).

Crude oil price drives USD/MYR exchange rate

Malaysia - Key economic indicators and ING forecast

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

27 May 2020

Covid-19: Who’s coming to the rescue? This bundle contains 8 Articles