Making the US trade deficit great again?

President Trump pledged to improve the US trade deficit. But the data is going the wrong way. How will he respond?

Trade data - where President Trump's luck seems to have run out

Since the start of his term, President Trump has seen a good run of economic data: strong growth in the US economy, increasing employment and rising wages, and – until recently – rapid equity market gains.

But on trade, a key focus in his presidential campaign, Trump’s luck hasn’t been as good. The US trade balance has worsened on his watch. In December the trade deficit stood at $53.1bn, putting the total trade deficit at $566bn for 2017 as a whole. That’s the highest annual figure since 2008, though as a share of GDP it is ‘only’ 2.9%, around half the all-time high was seen in 2006.

But things are still much better than they used to be

Taking a step back, the US trade deficit (and the current account balance, a better measure of the external balance) has been broadly stable over the past few years. Since 2010, the current account balance has averaged a deficit of 2.5% of GDP, compared to an average deficit of nearly 5% from 2002 to 2008.

Three broad trends account for this improvement:

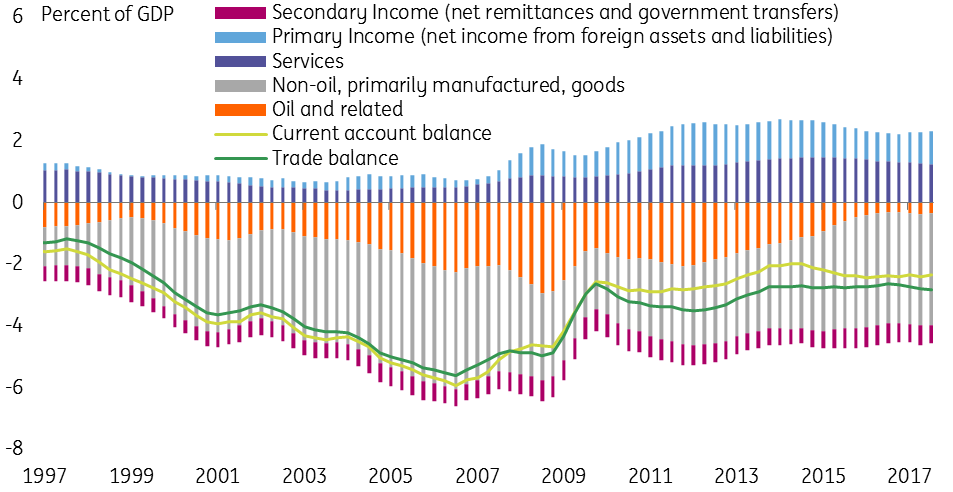

- Domestic oil production has increased dramatically thanks to the shale revolution. US production has roughly doubled to 10m barrels per day over the past ten years. Combined with lower oil prices, that has reduced the oil deficit (the orange bars in the chart below) from a peak close to 3% of GDP in 2008 to less than 0.5%.

- US services surplus (light blue bars) has increased steadily over the same period, partly off-setting the goods deficit.

- US’ net income from foreign assets and liabilities (yellow bars) has increased, again helping to off-set the goods deficit. That’s mainly due to record low-interest rates on US debt, which will start to reverse as US rates rise.

But the deficit in manufactured goods remains very large. Since the 2008-09 recession, when the good deficit shrunk rapidly, it has gradually widened again and is now back to the nearly 4% of GDP level last seen in 2006-07. That’s important because this is the part of the current account that matters most politically. When US politicians – and not only Trump – talk about trade, the focus tends to be on manufacturing jobs lost, not the strength of the US service sector.

US current account by component

Where does the deficit go from here?

To some extent, the US trade deficit is a result of the fact that over recent years the US economy has been doing better than key trade partners, in particular, Europe. A stronger US economy means more demand for imports, while weaker growth elsewhere means less demand for US exports. The appreciation of the US dollar from 2014-2016 also contributed to widening the deficit by making imports cheaper and exports more expensive.

As global growth is starting to look much healthier and the dollar has depreciated since the start of 2017, the US trade deficit may begin to close in 2018. But at the same time, the US tax cuts and spending increases legislated recently will push in the other direction, by stimulating US growth and thus demand for imports. The risk is that we see a further widening of the trade deficit in 2018.

What will Trump do?

The trade deficit is potentially problematic for the administration. A more protectionist approach to trade is a key plank in President Trump’s economic policy. So far, he has taken a number of steps, most significantly pulling out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement and launching a re-negotiation of NAFTA. But he has stopped short of implementing some of his more radical proposals from the election campaign, in particular introducing steep tariffs against China.

The worry remains that a widening trade deficit could prompt a more aggressive US stance. Trump’s trade team have been working on options, and further sector-specific tariffs like those recently imposed on solar panels and washing machines are likely. The US Treasury’s report on currency manipulation, due in April, is also worth watching closely, as it could be used to justify further measures.

Tariffs are unlikely to do much to improve the US deficit, not least as other countries may retaliate, damaging US exports. A more credible solution would be to convince trade partners, especially in Asia, to allow their trade surpluses to fall (through a combination of looser fiscal policy and/or less currency intervention). Though that is a tall order at the best of times, and especially when the US is actively increasing fiscal stimulus and pursuing openly protectionist policies.

What does all this mean for the dollar?

A couple of weeks ago Treasury Secretary Minuchin made headlines when he noted that a weaker dollar was helpful for the US trade balance. This appeared to abandon the US’ traditional ‘strong dollar’ policy. While the Treasury Secretary (and his boss) quickly ‘clarified’ that the administration believes a strong dollar is good for the US, the suspicion remains that actually, they wouldn’t mind further dollar depreciation. Certainly, a weaker dollar looks like the most straightforward way to square the administration’s desire to combine expansive fiscal policy and improving the US’ trade position.

We think much of the dollar weakness over the past year can be explained by changes in expected monetary policy and in particular the fact that ECB normalisation is finally coming into view. But the trade deficit and the deterioration of the US’ net external investment position risks becoming an additional dollar negative factor, much as it was in the pre-2008 period.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article