Global labour shortages: Just how bad can it get?

The lack of skilled workers is not only just another symptom of post-lockdown economics but also the result of more fundamental developments in the US, the eurozone and the UK

Shortages of all kinds have dominated economic headlines this year. After supply chain frictions, the end of lockdowns across the developed world has led to labour shortages in the US, the UK and the eurozone. We're going to look at the cyclical and more fundamental drivers of those shortages and examine the similarities and differences across the globe.

| 194,000 |

US jobs addedSeptember |

| Worse than expected | |

US - A productivity boom that comes at a cost

The US economy has fully regained all of the lost economic output brought about by the pandemic yet employment remains 5 million below February 2020’s level, which should, on the face of it, come at a major social cost. Yet, this isn’t due to a lack of worker demand. There are more than ten million job vacancies right now spread across all sectors with a record proportion of companies raising pay to try to attract staff. Instead, it is a problem with the supply of workers, which is both holding back output and increasing inflation pressures in the economy.

The conventional narrative is that we shouldn’t be too concerned because workers are set to flood back now that schools have returned to in-person tuition thereby giving parents greater flexibility to find a job. At the same time Covid vaccinations are making the workplace safer and extended and uprated unemployment benefits, which may have diminished the financial attractiveness of work, have now ended.

Where are the workers?

The problem is that in the US September jobs report the labour force participation rate actually fell, while employment, as a proportion of people of working age, is on a par only with the levels we saw in the depths of the Global Financial Crisis.

Admittedly it is early days – the September jobs numbers are calculated the week of the 12th so the October report may be a better time to make an assessment - but remember that half of all states ended the Federal unemployment benefits in July. For no improvement in worker participation by September is a concern.

Back for the holidays?

One possible explanation for this is that households have built up savings buffers and don’t have any urgency to return to work – cash, checking and time savings deposits have increased by $3.5tn since the end of 2019. We are coming up to the holiday season which will add to household expenses and that could incentivise more people to seek work, but we won’t know for sure for at least another couple of months.

But it could be more structural

We believe there is a more permanent loss of workers driven by a large number of older workers taking early retirement. The thought of returning to the office and the daily commute may seem unpalatable for many people and with surging equity markets having boosted 401k pension plans, early retirement may seem a very attractive option. On top of this, border closures will have hurt immigration and slower birth rates mean fewer young workers are now entering the workplace.

If correct, labour market shortages could persist for a good deal longer than the Federal Reserve expects, which will mean companies increasingly bidding up pay to attract staff. Not only that, but elevated quit rates suggest that companies may also have to raise pay to retain the staff they currently have given the high costs of worker turnover on moral, training and customer satisfaction. This points to more inflation pressures for the Fed to respond to with interest rates rising sooner and faster than currently priced by financial markets.

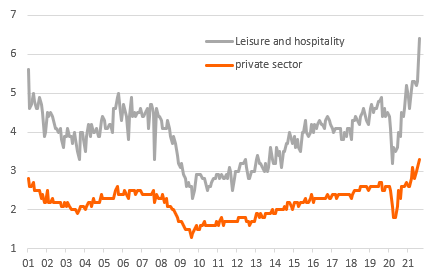

Proportion of US workers quitting their job to move to a new employer each month (%)

| 7.5% |

Eurozone unemployment rateClose to all-time lows |

Eurozone - a transitory problem with a permanent edge

The eurozone labour market has seen furlough schemes used in the pandemic at an unprecedented scale. This has made the labour market impact from the GDP shock seen in 2020 and 2021 as measured by the increase in unemployment unusually subdued. At 7.5%, the unemployment rate is now just 0.4 ppts away from its all-time low, reached in March last year. While concerns about labour shortages have started later than in the US and are less pressing than in the UK, they are increasingly mentioned as a concern for businesses. More than ever, businesses in industry report labour as a factor limiting production, in services this number is still below historical highs.

Transitory or more fundamental?

Some of the burden faced by businesses now is transitory, but the jury is still out on exactly how much of the problem will fade over the course of 2022. Arguments in favour of the transitional nature are continued slack in the labour market, ie untapped sources from the labour force, and still a sizeable number of employees in furlough schemes. On the other hand, many eurozone economies already experienced a lack of skilled workers pre-pandemic on the back of ageing and qualification mismatches. The current situation could simply be a return to the trends seen pre-pandemic once temporary mismatches fade.

An argument against a potential overheating of the eurozone labour market is the fact that the number of hours worked is still about 4% below pre-crisis levels, while employment is only 1.3% below. This productivity loss will have to be made up in the aftermath of the crisis, dampening further employment prospects. However, even if there are clear reasons to believe that the labour market has still sufficient untapped resources to avoid current tensions to quickly become permanent, some sectors of the labour market do see mismatches due to occupation changes or changes in economic activity.

Demographics are adding to structural labour shortage concerns in the eurozone

Ageing will put more pressure on the labour market

In the longer run, however, demographics argue in favour of more structural pressure on the labour market. The working-age population has been shrinking since 2010 and the active population has only been able to grow due to measures taken for people to work longer (think of increased retirement ages and disincentivizing early retirement schemes). In the coming years, we do expect the labour force to start to decline more structurally.

Higher wages in 2022 but not necessarily in all sectors

The rapid recovery of the labour market, the lack of skilled workers in certain sectors and the recent surge in inflation will in our view lead to higher wage growth in 2022. Mind you, the most recent data shows very low wage growth for 2020 and 2021, far below pre-crisis growth rates. However, this does not come as a surprise given the uncertainty, the economic slump and the increase in unemployment during the first lockdowns. Given the large sectoral differences, it could very well be that wage developments will also differ significantly across sectors and countries, making it harder to predict how overall eurozone wages will evolve. However, one way to fix the increasing mismatch between labour supply and labour demand could be wages, even if higher wages would not solve a qualifications mismatch.

| 2% |

Proportion of UK furloughed workersSeptember |

UK - Jobs mismatch offset by structural challenges for wage growth

Like the Eurozone, the UK is facing a mismatch in the jobs market – albeit perhaps a more severe one. Stories of lorry drivers and food preparation workers are a daily feature in the British press. Partly this is a function of a rapid rebound in hiring appetite. Job adverts in hospitality have stayed comfortably above pre-virus levels since the reopenings, while payroll-based measures of hiring have shown a rapid improvement in employment in these hard-hit areas.

Outward migration during the pandemic has amplified shortages

But shortages are also undoubtedly a function of the exodus of workers during the pandemic. ONS figures from the end of 2020 suggest there was a 7.4% fall in the number of EU nationals on UK payrolls, with declines particularly concentrated in the major cities. It’s not clear how much of that has been reversed now travel restrictions have eased, but post-Brexit visa rules (which make it trickier to work in the UK in lower-paid roles) mean it will be permanently harder for UK companies to source staff from overseas. Recent temporary visa changes for specific roles, including lorry drivers, are unlikely to make a huge difference to that story.

The ending of the furlough scheme will have increased slack

Still, while wage growth is pushing rapidly higher in these shortage areas, the situation is probably more balanced than headlines suggest. Around 2% of workers were still fully furloughed when the Job Retention scheme ended in September. And while we’re not expecting a huge increase in unemployment now wage support has stopped, we expect numbers of those working fewer hours than they’d like to increase, as well as a possible increase in involuntary retirement. What’s interesting is that furlough rates were still high over summer in a number of professions less obviously heavily affected by the pandemic.

UK unemployed-to-vacancy ratio is higher when furloughed employees included in the figures

The UK faces structural challenges too

We expect this mismatch to fade over the next year or so, and that in turn should reduce concerns that wage growth is going to stay sustained for longer. And like Europe, there are structural challenges too. The UK’s demographics challenge is perhaps less acute than some other parts of the EU, but the working-age population growth is nevertheless set to slow over the next decade. Like the US that may amplify some of the current shortages, but it's also a structural drag on UK potential growth. On that note, the UK’s productivity challenge seems likely to stay, partly because business investment was stagnant in the years between the 2016 Brexit referendum and the Covid-19 pandemic.

In short, the wage growth outlook is undoubtedly uncertain. The Bank of England looks poised to hike rates imminently, partly as a result of short-term pressures on wage growth. But the near-term cyclical challenges – linked to the furlough scheme – and medium-term structural ones – demographics and Brexit – suggest wage pressures are unlikely to justify the series of rate hikes markets now pricing in the UK.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

18 October 2021

ING Monthly: Curve surfing This bundle contains 11 Articles