Just how fit is the EU’s Fit for 55 climate strategy for Europe’s economy?

Fit for 55 is the European Commission’s package of measures to make sure it hits its climate targets. We don’t think economies will be impacted particularly strongly over the medium term. But as the EU turns its back on fossil fuels, some sectors could face major disruption

Unpacking the Fit for 55 package

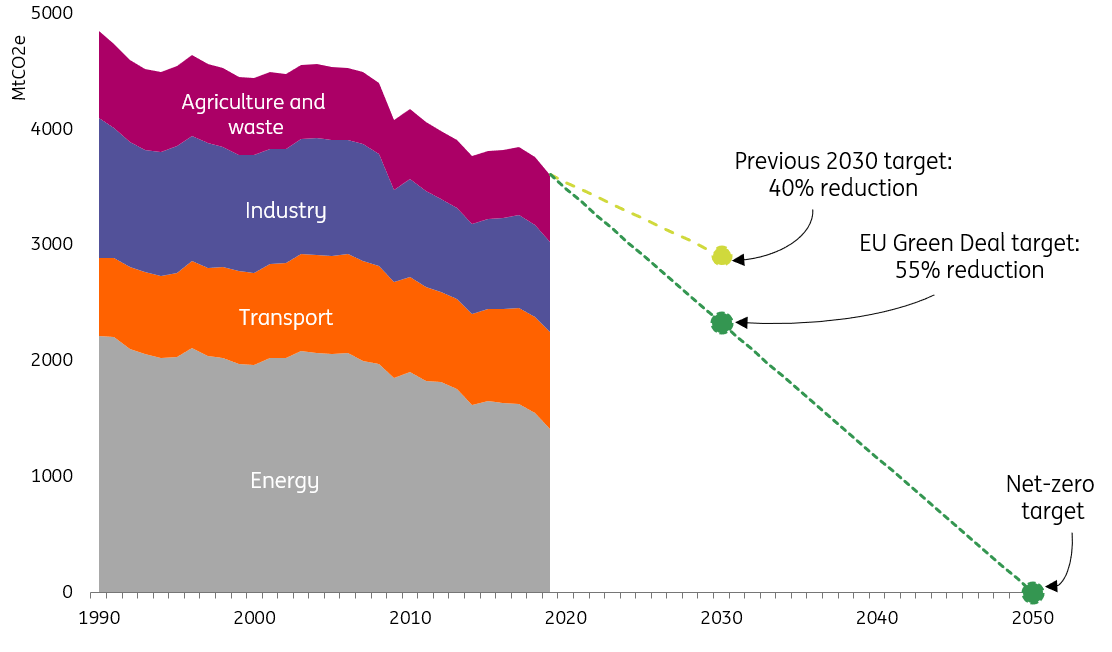

Fit for 55 is the European Commission’s legislative tool to make the ‘European Green Deal’ a reality. It targets cutting greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels), instead of the previous 40% target. With Fit for 55, the European Union is the first major economy to move from setting climate targets to planning climate action.

EU-27 historic emissions by sector, projection and targets

The package contains a dozen proposals (which can be found here) to overhaul energy legislation, introduce new technical standards, and push through minimum carbon taxation at the national level. Essentially, the package aims to push the cost of carbon higher, whether through direct pricing via carbon taxation and the emissions trading system (ETS) or implicit pricing via regulation.

Several of these new propositions focus on the residential and transportation sectors, which makes sense since the EU’s climate policy has historically predominantly focused on decarbonising the power and industrial sectors.

Key proposals included in the Fit for 55 package

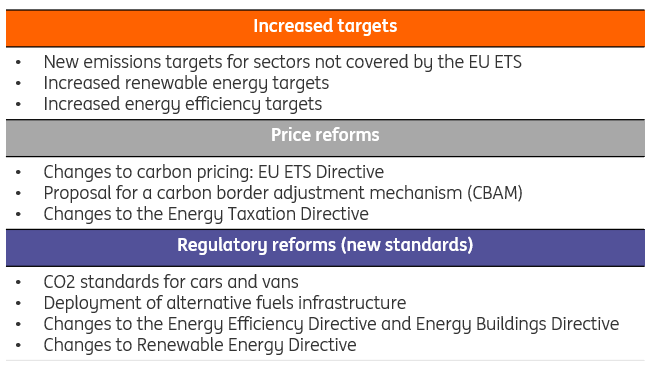

What’s new for carbon in Europe

The current ETS has been in place since 2005. It is a cap-and-trade scheme, a cost-efficient form of carbon pricing. According to the European Commission, the scheme has led to a large reduction in emissions since it was introduced. However, the scheme’s coverage only concerns the power sector and energy-intensive heavy industries (cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertiliser, etc.), accounting for about 40% of EU emissions.

As part of the Fit for 55 package, the European Commission announced that it would create a new ETS for two sectors: road transport and building heating, which account for a total of 40% of all EU emissions. Carbon prices have already tripled in 2021 to around €90 per ton CO2, making the business case for green technologies viable and fastening the transition, such as carbon capture and storage (CCS). We have already unravelled the economics of carbon pricing as an efficient instrument against climate change in a series of articles.

Europe's carbon price tripled in 2021 to €90 per ton CO2

European carbon price in mandatory EU ETS market, in €/CO2

Due to its impact on the competitiveness of EU industries, the European Commission also proposed to implement a green tariff on goods entering the EU to level up the playing field with the rest of the world on carbon pricing and to limit the risk of carbon leakages. The so-called carbon border adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) should come into force fully in 2026, after reporting only a three-year transition period. In a previous study, we already concluded that the current EU ETS price level at around €100 per ton CO2 particularly affects rubber and plastic production and base metals manufacturers' competitiveness in their domestic markets relative to foreign producers. High carbon prices without an international level playing field could motivate these industries to move production out of the EU.

According to the European Commission, revenues from emission trading would generate about €12bn per year on average between 2026-30 for the EU budget. The carbon border levy (CBAM) would generate another €1bn per year between 2026-2030 for the EU budget. Overall, both schemes would raise the EU budget by 1.2% by 2030.

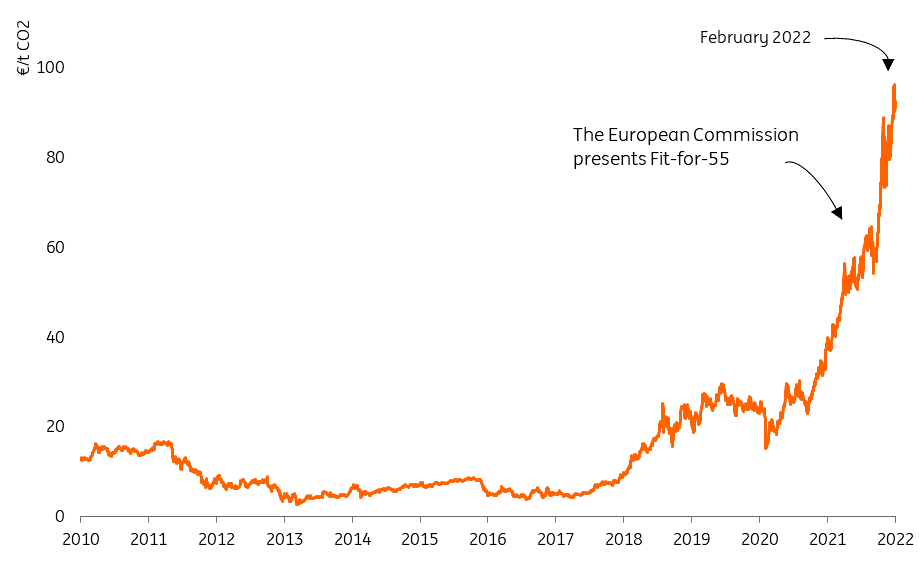

The EU carbon strategy relies on reforming the EU ETS and introducing a carbon border levy

Summary of the key changes and expected impacts induced by the new EU carbon strategy

Fit for 55 is likely to have a broadly neutral macro impact on GDP and employment

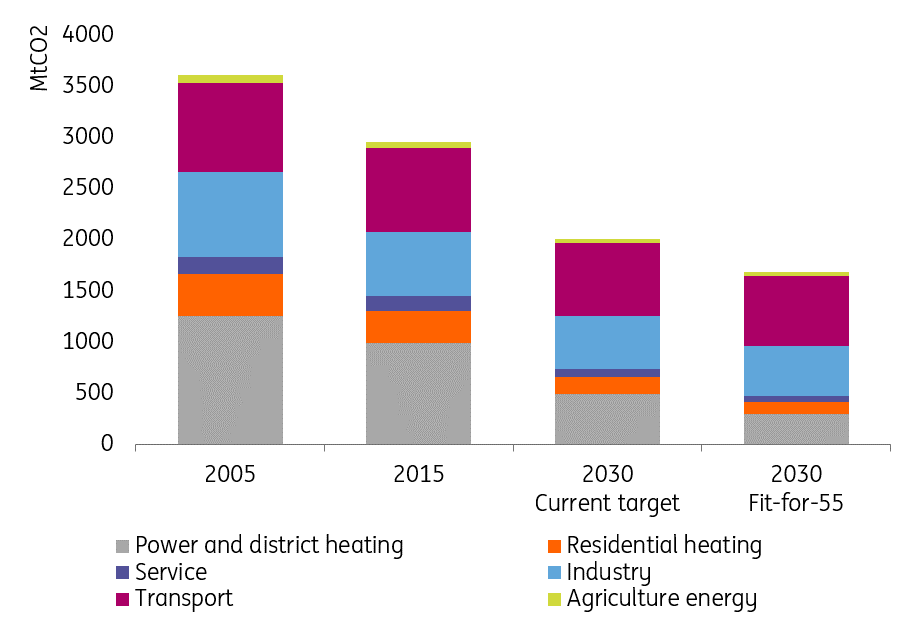

Should the Fit for 55 be fully implemented, the EU as a whole would be on track to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. The European Commission designed Fit for 55 to target a reduction of more than 60% of greenhouse gas emissions for power generation and residential heating by 2030 compared to 2015. Alongside carbon pricing, the Commission has set ambitious proposals to further roll-out renewable energies and building renovation by 2030. For example, it will require the public sector to renovate 3% of its buildings each year to drive the renovation wave – to compare with the current 1% for the overall building stock.

Power generation and residential heating would achieve a total reduction of more than 60% of emissions by 2030 (vs 2015)

Sectoral greenhouse gas emissions reductions from the energy system, current vs new target

We have summarised four recent empirical articles on the impact of carbon pricing on the growth rates of gross domestic product (GDP) and employment, see overview below. None of the articles below could find empirical evidence supporting the view that carbon taxes are job or growth killers, but several highlighted the sectoral discrepancies and potential regressive impacts on low-income households and microenterprises.

A growing empirical literature finds no robust negative effects of carbon pricing on GDP growth and overall employment

Other results, based on the example of Spain, further show that what governments do with carbon revenues ultimately shapes the response of the economy to the energy transition. This is something that the European Commission intends to address through the creation of a Social Climate Fund to recycle carbon revenues. In practice, it will be up to the Member States to design policy plans to use the fund’s money (i.e. lowering labour taxes, lump-sum redistribution to households, reducing public deficit etc.), so that macroeconomic response could vary across countries.

The simulation released as part of the European Commission’s impact assessment suggests that the impact of the Fit for 55 package on both GDP and employment is negligible. Investments from companies and governments should broadly benefit from the transition over the next decade and fuel short term demand. Three hypotheses to fund capital expenditures could unfold: (1) reallocation of expenditures from consumption to investment, (2) borrowing additional capital without crowding out consumption, and (3) fewer fossil fuel capital expenditures offset greener capital formation. However, in the short term, transition shocks might occur and country by country differences could be large, depending on the dependence on fossil fuels, the structure of demand and the vulnerability of households and small businesses.

In the best-case scenario, the EU could avoid the long-term costs associated with increased physical risks of climate change, but this of course depends on the willingness of other countries to act in a comprehensive and coordinated way.

Fossil fuel extraction industries to suffer the most, starting with coal

The required shift in investment patterns and the evolution of output will have lasting impacts on the composition of GDP and employment, with more negative repercussions in some sectors than others.

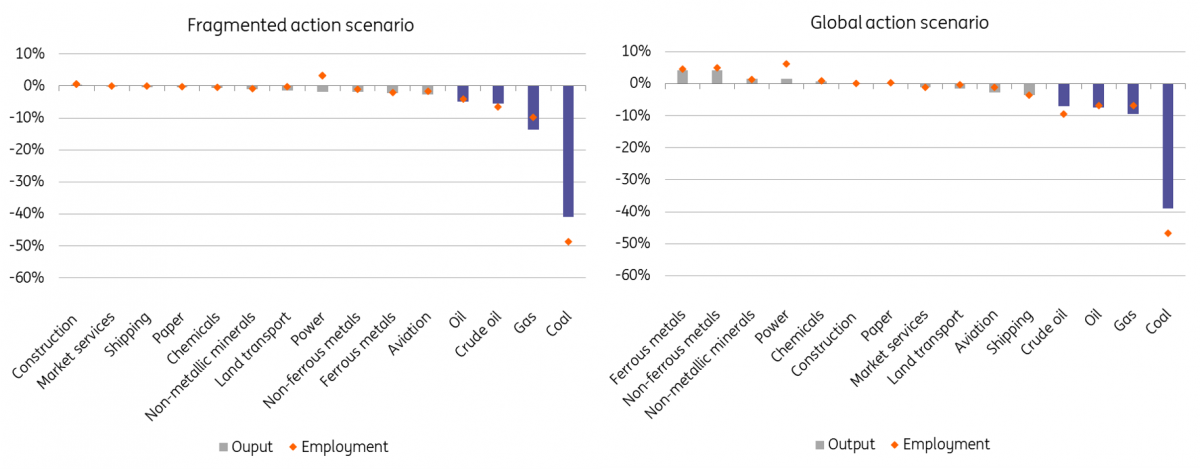

In this regard, the European Commission’s impact assessment provides two important conclusions, echoing those of the literature: (1) global coordination is key to maximise the benefits of the transition (notwithstanding the way that carbon revenues are recycled) and (2) the higher the openness of a sector to trade and the higher its carbon intensity, the larger the impact tends to be.

As expected, energy-intensive and internationally traded goods would suffer the most from the implementation of Fit for 55 under a scenario where other regions of the world don’t follow the EU’s climate lead, particularly fossil fuel extraction subsectors with coal losing more than 40% of its added value by 2030 compared to business-as-usual.

In terms of employment, the construction and the power sectors are likely to gain most from a higher level of climate ambition, given that the switch to renewable energies and the need to increase energy efficiency in buildings tend to be labour intensive. But expect labour frictions along the way related to the ability of the labour market to match demand and supply and to the capacity of the training/educational system to adapt to higher labour mobility needs (across regions, skillsets and sectors).

The higher the openness to trade of the sector and the carbon intensity, the larger the output and employment impacts should be

Average impact of -55% GHG reduction on EU sectoral output and employment by 2030 (deviation from baseline, %)

Not all EU countries will be affected in the same way. The countries most dependent on fossil fuels for power production, building heating or heavy industry will logically be the most exposed to losses in value. For employment, countries with an ageing and poorly-insulated building stock, such as Belgium, France and the Netherlands, could benefit from labour needs for building retrofit.

Green energy, transportation and buildings channel the investment wave

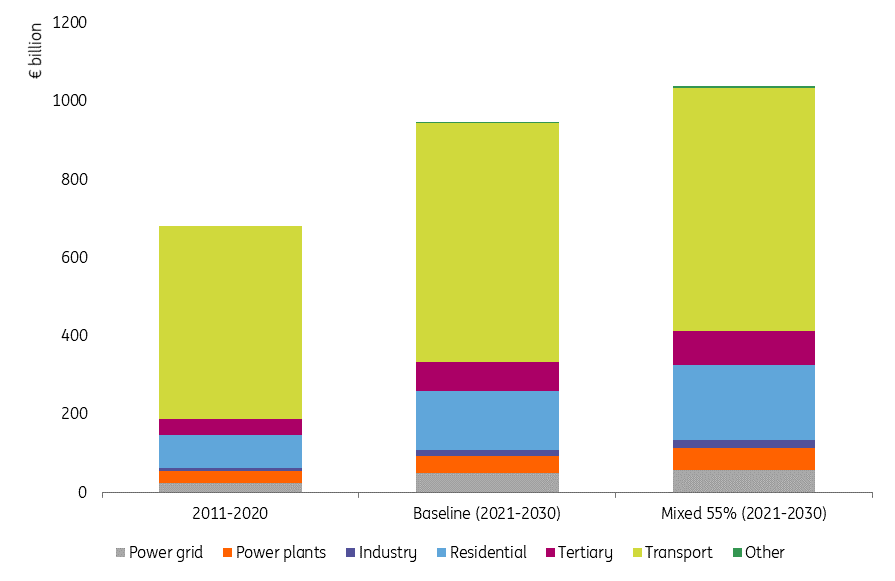

On the other hand, the decarbonisation of the economy would imply significant investments in electricity supply, energy-efficient buildings and low-carbon mobility solutions – investment themes that were already at the core of EU's recovery plan.

According to the European Commission, roughly a third of additional investment needs are in car replacement, compared to the previous decade. The same goes on for residential energy efficiency needs. Meaning additional annual investments in building and transportation should reach €360bn on average starting now (i.e. 2 percentage points of EU GDP) to raise relevant investments from €683bn per year in the last decade to more than €1tr in the next one.

Overall, Fit for 55 has the potential to trigger the reallocation of resources necessary for the transition, shifting capital away from the fossil fuel sector to green investments solutions in transportation, power supply and the building sectors.

Two-thirds of additional investment needs are in the transportation and residential sectors

Average annual investment needs to achieve Fit for 55 target

What are the next steps and can we expect this package to be passed?

Details of each proposal will be fiercely negotiated in parallel at the European Parliament and between EU countries within the European Council. Both the European Parliament and the European Council must jointly approve the plan. The ultimate deadline for the entire package to be adopted is before the next European Parliament elections in May 2024, but some proposals could be passed before given the stringent emissions reduction schedule. Some countries have already voiced their concerns, particularly over the risks that a second ETS for road transport and building heating would worsen the social challenges associated with the energy transition. A watering down of the current proposal is therefore not unlikely.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article