Japan: The problem of success

Japanese GDP remains very strong. That's raising thoughts about the end of quantitative easing and negative rates

2017 growth set to be strongest since 2010

With only one slight blip in 3Q16, when the economy grew at 0.9% quarter-on-quarter (annualised), Japan has recorded growth of above 1.0% (actually at or above 1.4%) in each of the last seven quarters. The revised 3Q17 GDP growth figures of 2.5% come hard on the heels of a 2.9% growth rate in 2Q17. Full year growth looks likely to come close to 2.0% (ING forecasts 1.8%), which would be the strongest growth performance since 2010, when Japan emerged from the global financial crisis. The extent, and persistence of Japan’s growth is leading some to question what this means for Bank of Japan (BoJ) policy. Currently, this targets 10-year Japanese government bonds (10Y JGBs) at about zero percent, and keeps the interest rate on policy-balances held by banks with the BoJ at -0.1%.

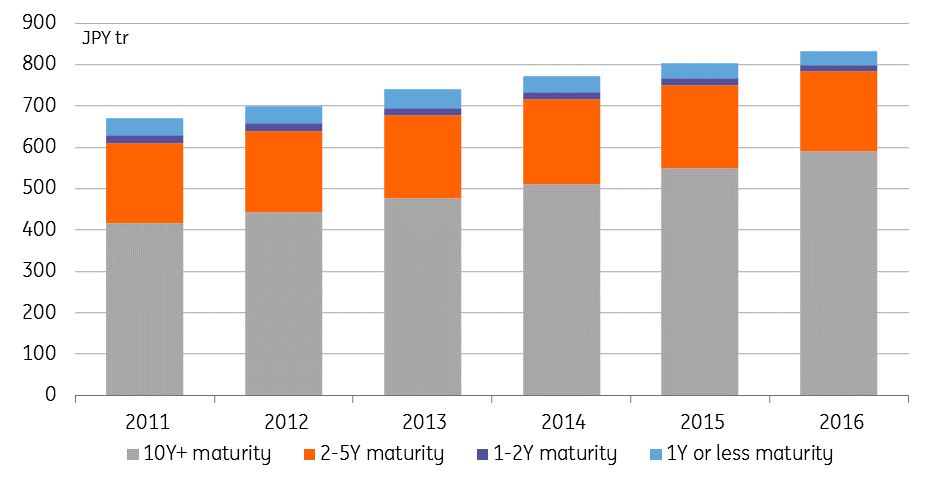

Central government debt outstanding

10-year government bond yields are on the rise

Like the yields on other G-3 bonds, Japan's government bonds have not escaped the recent rise in global yields, nosing up to about 0.05% from a recent trough of about 0.01%. That owes partly to overseas influences, the markets’ reluctant acceptance that the Fed’s ‘dot-plot’ of interest rate expectations is not so unrealistic and the beginning of the end of quantitative easing in the Eurozone. But is it reasonable to imagine that the BoJ could follow suit in 2018? Shorter maturity Japanese government bond yields remain negative, but they too have been nosing higher, suggesting some expectation of higher rates in the not-too-distant future. Sure, growth data are remarkably strong, and matched by similarly tight labour market data, but the BoJ has so far made little headway in raising inflation towards its 2% target.

With a debt stock more than double GDP, won’t raising rates create mayhem?

If Japan does eventually make some progress on inflation, or the BoJ eventually decides that 2% is simply the wrong inflation target and starts to raise rates, what then? When total government debt is in excess of a quadrillion yen (more than double GDP), shouldn’t this cause problems? What happens next depends on a number of moving parts, none of which are clear. Does inflation actually rise, lifting bond yields, but also likely raising nominal GDP. Does real GDP growth remain good, but inflation, and bond yields remain low, even as the BoJ hikes rates? Do we get something in between?

Rate hike this year is perfectly plausible

With the lion’s share of outstanding Japanese government debt of 10 years of longer maturity, even a return to 2% inflation and benchmark bond yields rising to a similar level will take some time to feed through into the government’s effective debt financing rate. But in our 'high' scenario, where bond yields and inflation both rise to around 2.0%, this adds a full percentage point of GDP to government debt service costs by 2028. Still, this isn’t a catastrophe, and if government revenues are also rising in line with nominal GDP, this should be quite manageable. In our 'low' scenario, where inflation and bond yields remain low, despite good real GDP growth, then the debt service costs will simply converge on the weighted average of long- and short-term bond yields times the debt stock as a proportion of GDP. There is, therefore, a perfectly plausible scenario in which the BoJ hikes rates this year. We don’t think it will, however. We suspect the BoJ will wish to see current real growth rates maintained for longer before relinquishing the comfort blanket of quantitative and qualitative monetary easing. And it will want to see some improvement in inflation. We doubt the latter will be forthcoming, even if the former remains strong. But it is not as silly an idea as it once sounded.

This article comes from our Monthly Economic Update. Download the full report here.

Download

Download article

5 January 2018

Asia economic round-up This bundle contains 5 Articles"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).