India’s economy needs more than stimulus. It needs reform

The failure of aggressive stimulus to jumpstart India's economy suggests it isn’t just in a cyclical slump; structural elements are also playing a part. Absent significant structural reforms, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vision of making India a $5 trillion economy in five years will remain a pipe dream

No end to the downtrend, just yet

The Indian economy has been on a weak growth path despite the massive fiscal and monetary policy stimulus it received last year. GDP growth slumped to more than a six-year low of 4.5% year-on-year in the July-September quarter of 2019.

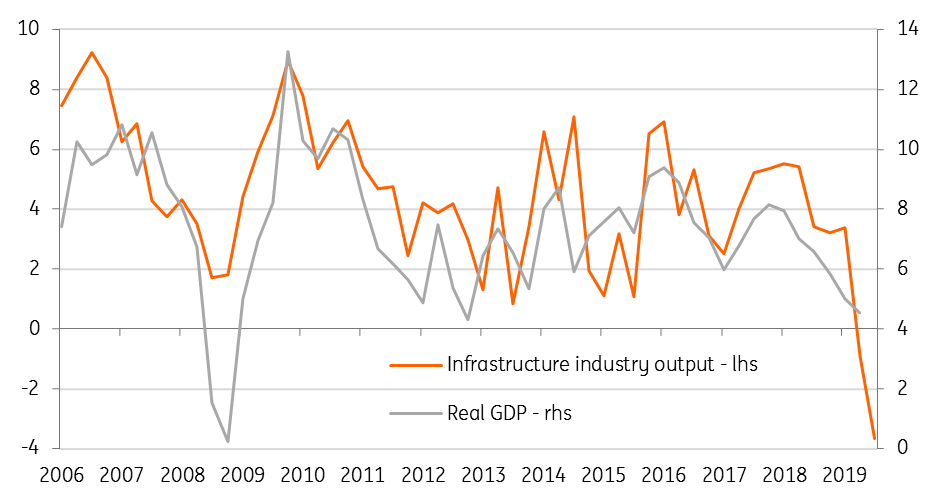

Hopefully, that quarter will turn out to be the low point in the current cycle. But maybe we are not there just yet. Monthly economic indicators show no sign of improvement in 3Q FY2019. The most significant among these indicators is the infrastructure industry output index, which posted its worst-ever fall in October (-5.8% YoY) and remained in negative territory in November. This index is a measure of the aggregate output of key infrastructure sectors (coal, crude oil, natural gas, petroleum refinery products, fertilisers, steel, cement and electricity) and it serves as a good guide for GDP growth.

Growth continues to head south (% year-on-year)

What’s behind it all? – weak domestic demand

Weak domestic demand has been dragging GDP growth down, averaging 4.8% in the first half of the fiscal year- a significant drop from the 6.8% rate in all of FY2018.

The contribution of private consumption to GDP growth has nearly halved to 2.3 percentage points (ppt), from 4.5ppt in FY2018. Likewise, the fixed capital formation contribution dropped sharply from 3.1ppt to only 0.8ppt, telling us that the Reserve Bank of India's (RBI) rapid easing (by 110 basis points through August) was of no use in stimulating lending and investment. A slightly better contribution from government consumption of 1.4ppt (up from 1ppt last year) may reflect fiscal efforts, though a large part of the stimulus from that side was only announced in August-September, and we have yet to see the full impact of that in government spending. Finally, mirroring weak domestic demand was a positive swing in the net trade contribution after two negative years.

On the supply side, the weakness was spread across all key industrial sectors - mining, manufacturing, utilities, and construction, while the growth of agriculture and services sectors has been steady so far in the current fiscal year compared to last.

Expenditure side GDP drivers (percentage point contribution to year-on-year growth)

Note: Bars may not stack up to total GDP growth due to statistical discrepancy.

An Asian underperformer

The ongoing economic slowdown comes as a significant blow to Prime Minister Modi's vision of making India a $5 trillion economy over the next five years (during his second term in office). Of course, this rests on the assumption that real GDP grows at a steady 7-8% annual rate, or about 12% nominal growth assuming that inflation hovers at the RBI's 4% policy target.

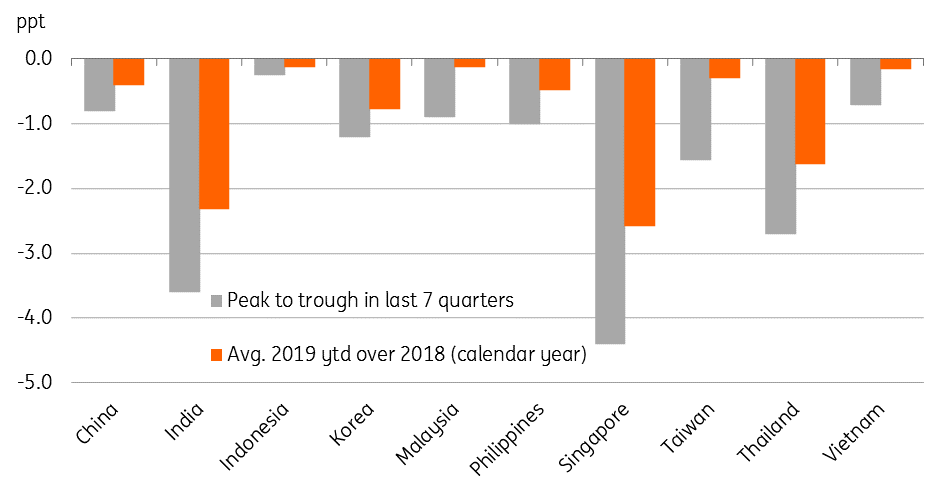

A near-halving of GDP growth since early 2018 (from 8.1% in 1Q 2018 to the most recent quarterly reading of 4.5%) is the steepest slowdown in Asia. It is even worse than the Chinese economy, which has been hit by the trade row with the US. Things might have been even worse if India had been more dependent on exports, or if it were a big electronics exporter like some of India's Asian counterparts, which were hit by the double whammy of the trade war and technology slump.

Nonetheless, the government’s 7% growth forecast for the year is now looking utterly unrealistic. The RBI's 5.0% forecast, which was cut from 6.1% at the December meeting, seems more reasonable and it also aligns with our view.

Asian growth slump since 2018 (percentage point change)

No longer the world's fastest-growing economy...

The accelerated slowdown has displaced India from the ranks of the world’s fastest-growing (developing) economies to a mediocre one.

Stimulus binge, by far the biggest in Asia

India's stimulus, including about 2% of GDP fiscal pump-priming and 135 basis points of central bank policy interest rate cuts.

Rapid central bank easing

Leading the global easing cycle, the RBI cut policy interest rates by a total of 135 basis points in 2019. Of this, 110bp of cuts came during the year through August, which should have kept growth from weakening sharply. But it clearly failed to revive bank lending. This failure can be put down to both weak investor sentiment and impediments to policy transmission

The RBI surprisingly paused at the December meeting, raising the possibility that this would be all the easing in this cycle. If historic lows in policy rates are any guide – 4.50% for the repo rate and 3.25% for the reverse repo rate at the height of the 2009 global financial crisis – we could see these levels reached again, unless the growth outlook improves. We do see growth getting some lift this year, at least from favourable base effects, if not an underlying recovery of demand.

Will inflation, which has now surged past the central bank's 2-6% target (7.4% in December) and is likely to stay above it for most of this year, deter further rate cuts? In the past, even double-digit inflation has not been a big hurdle for RBI easing.

However, the RBI seems to be coming to terms with inflation risk as Governor Shaktikanta Das recently highlighted. A shift in the policy stance to neutral from accommodative is a reasonable starting point for the central bank's next policy meeting in early February. We no longer expect the RBI to cut rates this year. Nor do we see any policy tightening on the horizon, at least not until GDP growth recovers to more than 7%. That isn't going to happen anytime soon.

Lower interest rates failed to revive lending

Flood of fiscal stimulus

Complementing aggressive monetary easing last year was a strong fiscal thrust, including populist pre-election measures of a $10.6 billion support package for farmers, a $2.7 billion rural road programme, an increase in the income tax exemption limit and a relaxation in property taxes, etc.-- all part of the interim budget in February 2019.

Taking advantage of the RBI's $24 billion in dividend and surplus capital transfer to the government in August, new Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman then opened the floodgates for more fiscal stimulus totalling about $37 billion in all (1.4% of GDP), which was followed by the announcement in December of a $1.5 trillion, five-year infrastructure investment plan.

Here are some of her key announcements:

- 23 August: Withdrawal of surcharge on long and short-term capital gains tax on foreign portfolio and domestic investors; $9.8 billion (INR 700 billion) capital injection for public sector banks; lifting of curbs on new vehicle purchases by government departments.

- 29 August: Easing of foreign investment regulation for retail, manufacturing and coal mining sectors. Relaxing local sourcing norms for foreign companies selling their own brands in India. Removal of caps on investment in commercial coal mining. Up to 26% investment permitted in digital media.

- 30 August: Consolidating 10 public sector banks into four - A) Punjab National Bank, Oriental Bank of Commerce, and United Bank; B) Canara Bank and Syndicate Bank; C) Union Bank of India, Andhra Bank and Corporation Bank; and D) Allahabad Bank and Indian Bank.

- 14 September: $7 billion tax incentive for exporters. Measures to boost the real estate sector.

- 20 September: $20 billion corporate tax reduction for domestic companies. Reduction of Goods and Services Tax on hotel rooms (18% from 28%) and catering services (5% from 18%), but a hike on caffeinated beverages (40% from 28%).

- 31 December: $1.5 trillion infrastructure spending plan for the next five years.

The pre-election stimulus clearly failed to revive growth. Although, as noted earlier, we have yet to see the full impact of the latest measures on real demand. Hopefully, they will bear some fruit in the year ahead.

Tax cuts – a boon or bane?

The easing of income and corporate taxes is a significant positive step in the latest policy efforts to reinvigorate demand. The new corporate tax rate of 22% (15% for start-ups) puts India on a par with other Asian neighbours (standard rate of about 25% in most Asian countries, 17% in Singapore and Hong Kong).

However, the benefits of such measures are typically only realised over the longer-term. First, ill-timed tax cuts can depress government revenue just when it needs to spend more. The big-bang corporate tax cut is estimated to cost the government $20 billion in lost revenue. And businesses hit by the economic slowdown may not even generate profits, let alone be paying any tax on them. Moreover, it is probably unrealistic to think that lower tax rates would stimulate capital investment at a time when business prospects are clouded by weak demand. Though this may pay dividends in the future.

Asian corporate tax rates (%) - India has become competitive

Policy-driven risks

Aggressive fiscal stimulus means another year of overshooting the fiscal deficit. The official projection for the deficit to reach 3.3% of GDP this year is way too optimistic. We recently raised our deficit forecast for the current year from 3.5% to 3.9%, wiping out nearly all the consolidation over the last three years.

There is also no clarity about how the government will be financing this wide deficit. The $24 billion windfall from the RBI won’t be enough to plug the gap. Nor can the government continue to rely on such monetization of the deficit forever. The plan of tapping the international debt market has been shelved amid an uncertain market environment, while negative sovereign rating actions -- Moody’s downgrade of India’s BBB rating outlook from stable to negative in October and a similar warning by S&P in December -- have dented foreign investor confidence. This, in turn, means a greater strain on domestic debt markets, where excessive government borrowing is crowding out private investment – a recipe for continued sluggish GDP growth ahead.

Finally, it’s hard to ignore the inflationary possibilities of the RBI's policy easing. As noted earlier, 7.4% inflation in December was the highest in more than five years and well above the RBI’s 2-6% target range. Although weather-related supply shocks to food prices are behind most of the latest inflation spike, policy-driven influences through the weak currency have also been contributing. Moreover, high inflation has a further reverse spillover onto public finances in that it keeps market yields high, making public borrowing and debt-service more expensive – all causing further deterioration of the fiscal situation.

CPI inflation - there is more to it than food price shocks

Slowdown isn't just cyclical, but structural too

Failure of all the stimulus to jumpstart the economy suggests this isn’t just a cyclical slump. Structural elements are playing their part too, probably more intensely now given the weak growth outlook.

Weak monetary policy transmission has been a key issue for the economy and financial system. As the RBI's latest policy statement pointed out, against a total 135bp of policy rate cuts this year, the one-year median marginal cost of fund-based lending rate (MCLR) declined by only 49bp, and the weighted average lending rate (WALR) on fresh rupee loans of commercial banks was down by just 44bp.

The liquidity troubles of shadow banks since late 2018 and steadily rising non-performing assets (NPAs) of public sector banks (estimated at about 15% of total assets) have stymied pass-through of RBI monetary easing to the banking sector, by squeezing the loanable funds available to banks and forcing them to tread a more cautious path in extending loans. Moreover, the RBI repurchase rate, the policy rate currently at 5.15%, doesn’t determine banks’ funding costs. More important is the rate banks pay to deposits, which are typically less responsive to monetary policy changes given a large chunk of these (around 65%) are term deposits.

Financial sector stability is vital in restoring investor confidence in the economy. Abrupt policy changes, like demonetisation in late 2016, chaotic implementation of the goods and services tax in mid-2018, and the shadow bank crisis since late 2018 are not helping. The impact of the demonetisation of high-denomination currency notes three years ago, which jolted the entire financial system with a hit particularly to the country's large unorganised sector, is still reverberating today. The shadow bank jitters are now turning into another structural headache.

If any country does not have a stable well-capitalised financial sector, then it will be difficult to get transmission from monetary policy to the real economy at the right rates. – RBI ex-deputy Governor Viral Acharya

Among other hurdles for the economy reaching its growth potential are poor infrastructure, long delays and cost overruns in new infrastructure projects, and difficulties in harnessing private investment in this sector. According to the Finance Ministry’s Economic Survey for FY2018, the economy needs about $200 billion in infrastructure investment annually, whereas it’s been able to garner just over half of this. Tight public finances entail a greater reliance on the flow of private capital to plug the gap.

Further adding to these structural troubles are weak public finances and high public sector debt crowding out private investment, weak labour laws hindering private sector and foreign investment flows, high unemployment, relatively high income-tax rates depressing consumer spending, and above all, red tape.

Without significant reforms in these areas, Prime Minister Modi’s vision of boosting India to a $5 trillion economy in his second term will remain a distant reality. His latest privatisation push to sell the entire stake in two state-owned companies, in the oil refining and shipping sectors, as well as reducing holdings below 51% in some other public sector companies, is a move in the right direction. Hope rests on the upcoming FY 2020 Budget on 1 February, building on these initiatives as well as laying out concrete steps toward the implementation of the recently announced $1.5 trillion, five-year infrastructure investment plan.

Twin deficits - a long-term problem

Some relief from external payments stress

One silver lining in India's domestic weakness is the reduced strain on India’s external payment situation. Barring occasional spikes on bad news in the Middle East, global crude oil prices were well-behaved last year and this helped to shrink India’s trade and current account deficit via a lower fuel import bill.

At $110 billion in the first eight months of the current fiscal year (April to November 2019), the customs-based trade deficit was $23 billion smaller than a year ago. The current account deficit of $20 billion in the first half of the fiscal year compares with $35 billion a year ago. We forecast a full-year FY2019 current deficit equivalent to 1.8% of GDP, down from 2.1% the previous year.

The overall payments position has been improving, as evident from surging foreign exchange reserves. India’s $451 billion of exchange reserves at the end of November, is the fourth biggest pile among Asian countries (after China, Japan, and Taiwan).

Rising foreign exchange reserves (US$ billion)

INR – Asia’s weakest currency again

The unfriendly external environment, domestic political noise, a weak economy, and policy-related drags made the Indian rupee (INR) an Asian underperformer for the second year running in 2019. However, like its Asian peers, the INR is feeling some relief from recent trading in the Chinese yuan (CNY), the front-line currency in the global trade war. The USD/INR exchange rate appears to have settled in a 71-72 trading range since August as US-China trade relations started to warm up, while the RBI’s rate cut pause in December came as a reprieve for the currency.

What's driving the rupee weakness

Political headwind persists

Aside from spikes in global geopolitical risks taking a toll on the INR, domestic political jitters continue to be an ongoing overhang for Indian markets. Hopes that Modi’s landslide victory in the general election would remove both economic and political uncertainty were rather misplaced. Clearly, there was no good news on the economic front despite the raft of policy initiatives to revive the economy.

Coming on top of his economic woes have been ecological issues, such as the recent air pollution in the capital city of Delhi, and a lack of political accountability, despite PM Modi’s election pledge to improve the environment.

And, in what is being seen as an attempt to deflect attention from the government’s poor handling of the economy, the surge in the government's nationalistic political directives (stripping the disputed state of Jammu and Kashmir of its autonomy in August, and the passage of the controversial citizenship bill in December -- sparking a nationwide backlash against the administration) have also weighed on investor sentiment. Modi and his Party's (Bhartiya Janata Party) popularity have continued to slide as shown by continued losses in recent state elections, most recently in Jharkhand and Maharashtra. The next test will be elections in Delhi in February and numerous bi-elections over the course of the year.

All that matters for investors and markets is stability on both economic and political fronts. History teaches that the two may not co-exist in India and, in fact, both may well be absent in the year ahead. While structural bottlenecks will continue to hold back growth for the second year running, we don’t see political headwinds to the economy subsiding just yet.

Bottom line – still, a bumpy road ahead

We may be close to the trough of the current growth cycle, though the continued external headwinds and domestic structural impediments are likely to make a recovery in 2020 painfully slow. Without significant steps to address structural issues, it’s hard to see the economy regaining its 7-8% growth potential anytime soon, at least not over the next couple of years. This means a continued negative output gap, while growth-centric policies and a weak currency will play their part in keeping inflation elevated.

We consider 7% GDP growth a pre-requisite for the RBI to unwind some of its recent policy easing. That’s not on our forecasting horizon out to 2021. On the fiscal front, policy will remain accommodative but a wider budget deficit over the next few years won’t leave much room for fiscal manoeuvring to support growth.

External and domestic policy-related influences will continue to determine INR volatility in 2020. Despite the US and China signing their phase one trade deal, we aren't ruling out further occasional spikes in the trade war in 2020 exerting more weakening pressure on the INR. From today's spot rate of just under USD/INR 71.0 we see more upside than downside risk to the INR over 2020, which could trade towards the higher end of our 71-73 forecast trading range by the end of this quarter.

India - Key economic indicators and ING forecasts

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

16 January 2020

Good MornING Asia - 17 January 2020 This bundle contains 5 Articles