India’s best shot at the Covid-19 second wave

Lockdowns are “easy” but arguably quite an ineffective means of stamping out Covid-19 in the world’s most populous country. India's massive vaccination drive appears to be faltering too. This leaves a strong political will and public awareness as the best hope. But that won’t spare the economy from a rough ride ahead amid ongoing macro policy paralysis

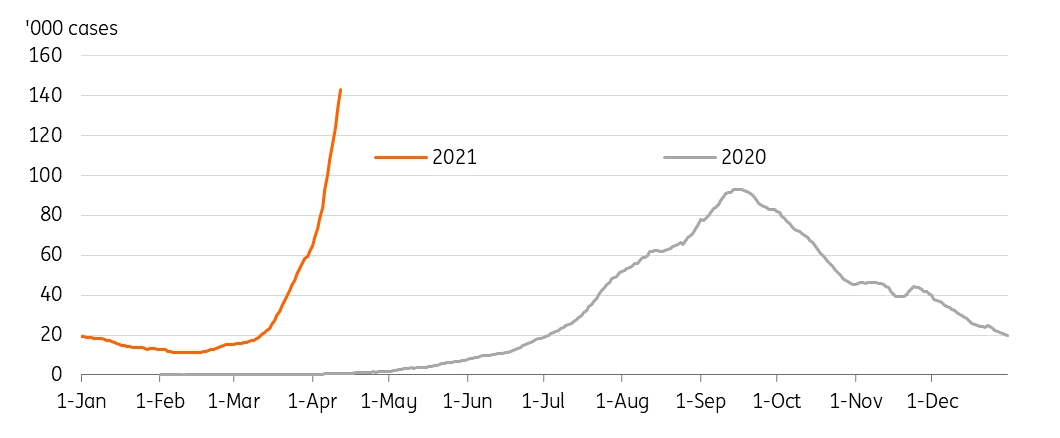

Much worse second wave

Daily new Covid-19 infections surged to 170k over the last weekend (11 April), the highest ever since the onset of the pandemic in February 2020. The current daily infection rate significantly dwarfs daily new cases in the USA and Brazil (54k and 39k, respectively) as of this writing. With the total number of infections in India now at 13.69 million, India has regained its second spot from Brazil in terms of total infections globally. Hopefully, India isn’t chasing the US to the top spot (31.99 million), though at the current rate of spread it could get there by year-end.

The intensity of the second wave of the pandemic, which is far stronger than the first

A nearly eight-fold jump in daily cases over just one month underscores the intensity of the second wave of the pandemic, which is far stronger than the first wave. That first wave took six months to rise before a daily peak of 98k in mid-September 2020. The geographical spread appears to be less widespread this time around with nearly one-third of the total daily infections concentrated in the single state of Maharashtra, though that’s down from one-half just days ago. Maharashtra has been dominating the charts since the beginning of the pandemic with cumulative cases so far of 3.34 million and one-third of the total Covid-19 deaths in the country.

The other states are catching up too. Together with Maharashtra, nine other states (see the graph below) accounted for 76% of daily new infections, and five of these (Maharashtra, Chattisgarh, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh and Kerala) together make up over 70% of the country’s active caseload of 1.3 million.

All that said, apparently strong immunity of the Indian population relative to other countries has saved them from high mortality during this pandemic. Total deaths of 171k so far are much smaller compared to 355k in Brazil or 576k in the US. The number of recoveries from total infections in India stands at 12.3 million (12 million in Brazil and 25 million in the US).

India's daily cases of Covid-19

7-day moving average

Top 10 states by daily infection

How did they get here?

The questions all this begs are: How did they get here, and how well prepared are the authorities to tackle this second pandemic wave? Here are some of the factors contributing to today’s situation and lack of political will towards its build-up.

- The legacy of the first wave: Despite launching one of the strictest lockdowns in the world in March last year, India’s containment efforts during the first wave of the pandemic proved to be insufficient. Nearly three months of strict lockdown was the best shot at breaking the infection chain. Unfortunately, it was an opportunity lost and left the country at the top of the world chart for total infections.

- Reopening frenzy: The reopening of the economy from the long lockdown from March to June 2020 gave rise to a lot of pent-up energy. People living hand-to-mouth on a daily basis in the large, unorganised sectors set out to recover their lost livelihoods. As mass movement gathered pace, the poor testing, tracing, and isolation efforts, inadequate medical infrastructure, and large public gatherings in social and political spheres sowed the seeds of the second wave.

- Democracy vs. pandemic: Like some of its global counterparts, the world’s biggest democracy was tested severely during the Covid-19 outbreak. Incoherent policymaking at the centre and state levels deserve some blame here. The abrupt announcement of lockdown by the central government caught state governments as well as the general population off guard and was followed by mass migration that fuelled the disease to the levels we see today.

- Misguided people: Instead of tackling the spread of the disease through appropriate policy actions, politicians saw an opportunity in the health crisis to pursue their political agenda towards a slew of state elections. The ruling administration strived to dampen all the negativity and pessimism among the people about the pandemic and strengthen its image. False media reports, slurs, anti-slurs – all these left people misguided about the genuine underlying situation.

- Lack of public awareness: The total disregard for safety measures during election rallies and religious and social gatherings as well as several months of nationwide anti-government protests by farmers also contributed to the rapid spread of the virus. We may see more of the same as four states and a union territory are holding elections during April and May this year.

- Misdirected economic stimulus: While macro policies in several other countries were geared towards minimising the financial misery via cash handouts, subsidies, tax incentives, etc., India's Covid-19 fiscal stimulus of over 10% of GDP has comprised mainly big bang structural reforms – leaving people to support themselves. And, instead of mobilising resources to facilitate the growing demands on the healthcare system, the authorities resorted to an otherwise easier policy tool to curb the virus -- lockdowns.

National vaccination progress

Vaccination drive hits a snag

With a much worse second wave putting an exceptional strain on India’s healthcare system, things will likely get worse before they get better. Moreover, as in many other countries around the world, there may well be multiple waves and variants of the virus potentially taking a toll on the healthcare system as well as the economy.

At the current pace, it would take more than two years to complete the inoculation of the entire population.

One of the world’s biggest vaccination programmes kicked off in India in mid-January with healthcare and frontline workers initial recipients of the jab. The programme aims to inoculate 22% of the entire 1.37 billion population by July this year. This target seems optimistic, with only 108 million doses administered so far in the first three months of the drive. At the current 7-day average of about 3.6 million doses administered per day, and two doses required per person, it would take more than two years to complete the inoculation of the entire population.

So although India’s is still the fastest vaccination programme in the world in absolute terms, leaving the US and China way behind, reports of a shortage of vaccines have been making headlines lately. The supply jitters stemming from raw material shortages hindering production bode ill for the future of India’s vaccination programme. This is despite the government’s claims of sufficient stock and moves to hold back all exports of locally manufactured Oxford-AstraZeneca jabs. As a further blow to the programme, the recurrence of the virus in some people, despite completing their course of vaccination, has started to raise questions about the effectiveness of these shots. Such scepticism and possible misunderstanding about vaccinations may have a deterring effect, especially among the largely illiterate populace, many of whom can't even register for the dose.

Top 10 states by vaccinations so far

It all comes down to the economy

The recovery of the Indian economy from a record plunge in 2020 was coming along quite well compared to most of its Asian neighbours. India is the second economy in the region after China to swing back to a slightly positive year-on-year GDP growth of 0.4% in the October-December quarter or 3Q of FY2020 (financial year in India runs from April to March). Part of this turnaround owes to base year effects. However, the underlying recovery continues to be anaemic.

Tighter movement restrictions in the worst affected states will accumulate to be a significant hit to the overall Indian economy.

As the economy started to ride the second wave of the pandemic, real activity growth began to weaken, and inflation started to move higher again. Industrial production posted a 2.2% year-on-year fall in the first two months of 2021. Exports haven’t been a big support for manufacturing, while domestic spending continues to suffer amid weak consumer and business confidence. Meanwhile, supply shocks to food and fuel prices have started to push inflation towards the Reserve Bank of India’s 6% policy limit in recent months (5.5% in March).

These trends have further to run as the gravity of the second wave of the pandemic unfolds via increasing restrictions on economic activity. States like Maharashtra are already going through tight movement restrictions, including night-time curfews and complete lockdowns over the weekends. Many more are likely to follow suit – the state governments of Delhi and Karnataka have just warned of lockdowns. Maharashtra has been the most industrious of all 28 Indian states (and eight union territories), contributing close to 14% to the nation’s GDP. Together with the selective restrictions in the most affected states, this will be a significant hit to the overall Indian economy.

GDP contribution by key states - percent in FY2019

Growth forecast downgrade

We don’t think the Modi government is keen to entirely stifle the economy with a nationwide lockdown. Doing so would not go down well in the run-up to looming state elections. As such, the hit to the economy during the second wave of Covid-19 is expected to be less pronounced than that during the first wave. On the flip side, year-on-year activity growth will also get some lift from the low base effects. And, so will headline GDP growth.

We are scaling back our GDP growth view for FY2021 from 9.2% to 7.8%.

Even so, a downgrade of India’s economic outlook seems utterly inevitable in light of the latest developments. We are scaling back our GDP growth view for FY2021 from 9.2% to 7.8%. This is still a decent bounce from an estimated -7.2% fall in FY2020 but largely reflects base effects. We should see strong year-on-year growth in the high teens in the current quarter, followed by tapering to low single-digit growth in subsequent quarters. This is our base case view. In a worst-case scenario with intensified Covid-19 restrictions across the whole country, annual GDP growth in FY2021 could fall to low single-digits or even negative.

Meanwhile, supply disruptions to food and fuel prices will continue to pressure CPI inflation higher over the course of this year. If not breaching the central bank's 6% policy limit, it should stay close to that limit in our base case forecast. And, with weak domestic demand weighing on imports, the external payments situations should remain comfortable.

Our inflation forecast for FY2021 is 5.8% and we estimate a current account deficit equivalent to -0.8% of GDP. This compares to 6.3% and +0.4%, respectively, in FY2020.

GDP growth forecast

Consumer price inflation

Macro policy paralysis

The prevailing “weak growth-high inflation” dynamic suggests that the Reserve Bank of India's monetary policy status quo should prevail throughout this year, while there is nothing much to expect on fiscal policy.

The RBI has opened its liquidity taps wide, though we doubt this will do any good to the economy while the pandemic hinders business confidence

Instead of cutting policy interest rates or the cash reserve ratio in the latest policy meeting, in early April, the RBI opened its liquidity taps wide. Governor Shaktikanta Das pledged to buy up to INR 1 trillion of bonds in the secondary market in the current quarter through the newly announced G-sec (government security) Acquisition Programme (G-SAP). The move was aimed at capping borrowing costs and softening the Covid-19 blow isn’t going to be a one-off but will be continued until the situation improves. This complements the existing ‘operation twist’ and open market operations to drive down the yields as the government taps the market for a record borrowing of INR14.3 trillion this year to plug the budget gap.

Aggressive RBI easing of 225bp of policy rate cuts and liquidity injections last year failed to stimulate bank lending. We are sceptical of the latest measures going any further as the pandemic hinders business confidence.

Fiscal policy also appears to have maxed out after a record spending surge in the last year. The government aims to cut down the fiscal deficit from an estimated 9.5% of GDP in FY2020 to 6.8% in FY2021, which is largely dependent on the assumption that GDP growth accelerates over 10% this year while the INR 34.8 trillion spending budget for the year is little changed from last year.

Underdog markets? Not anymore

Despite some occasional bouts of weakness, both local currency government bonds and the INR were resilient to market turmoil from January to March. This is In contrast to significant spikes in Southeast Asian government bond yields in response to the US Treasury selloff; India’s 10-year yield didn’t drift much higher from the 6% level it has hovered near since May 2020. And, the INR turned out to be one of Asia’s best FX performers in the first quarter of 2021.

We now see the INR giving back almost all the gains it made against the USD since early 2020 over the next three months.

The RBI’s new liquidity-boosting policy may sustain the resiliency of government bonds in the months ahead but not so much that of the INR. Attesting to this is the INR's 1.5% depreciation against the USD to 74.55 on the day of the RBI’s latest policy announcement on 7 April. And there is no end in sight to this depreciation trend; the USD/INR traded up to a 10-month high of 75.50 as of writing.

We now see the INR possibly giving back all the gains it made against the USD since early 2020, pushing the USD/INR to the then high of 76.80, over the next three months. This is a sharp downgrade from our earlier 3-month view of 74.30. We are hopeful of some consolidation below 75.00 towards the end of 2021 as the Covid-19 situation improves. For now, these are just the hopes.

India: Economic forecast summary

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

14 April 2021

Good MornING Asia - 15 April 2021 This bundle contains 3 Articles