IMF: Weakening fiscal balance sheets biggest concern for emerging markets beyond 2021

The IMF upgraded its global growth projection to 6.0% in 2021 and 4.4% in 2022 in its latest World Economic Outlook (vs 5.5% and 4.2%, respectively, in January). This follows a 3.3% contraction in 2020. We highlight regional growth outlooks and analyse medium-term projections for GDP growth, inflation, current account and fiscal balance sheets

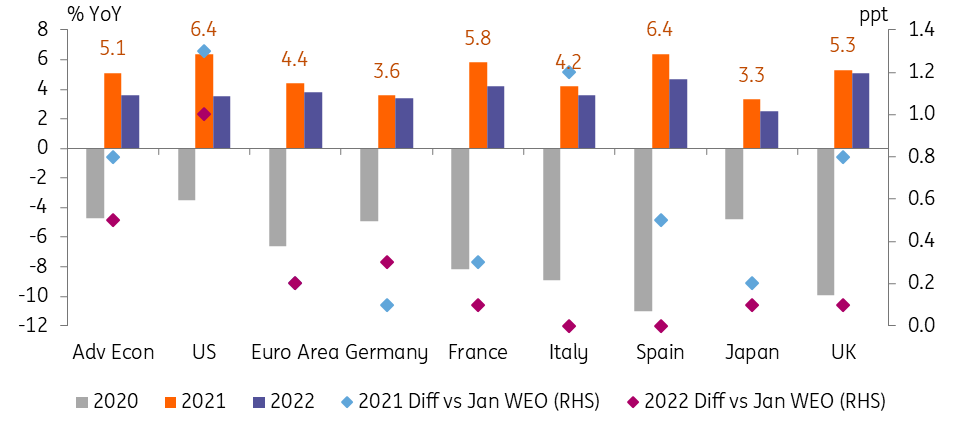

Country groups and selected countries: GDP growth in 2020-22 (% YoY)

The underlying story remains similar to the World Economic Outlook report in January, with the uplift mainly stemming from advanced economies which are expected to grow by 5.1% in 2021 and 3.6% in 2022 (vs 4.3% and 3.1%, expectations respectively, in January), thanks to the vaccine rollout momentum which will gather pace in 2H21 and additional fiscal support in a few larger economies, notably the US where 2021 growth has been revised up by 1.3 percentage points higher to 6.4%.

Advanced Economies: GDP growth in 2020-22 (% YoY)

Emerging market and developing economies

Meanwhile, aggregate growth for emerging market and developing economies (EMDE) is seen at 6.7% and 5.0% (vs 6.3% and 5.0%) although recovery prospects diverge across different regions and countries:

Emerging and Developing Asia (+8.6% in 2021; +6.0% in 2022) remain the growth locomotive of the emerging and developing world. India which had already seen a large upgrade in January (+2.7ppt vs October 2020) was further revised upwards by another 1ppt to 12.5% for the fiscal year ending March 2022. China’s 2021 growth forecast has been revised upwards by 0.3ppt to 8.4%.

In contrast, most larger ASEAN economies are expected to see a delayed recovery due to still high Covid-19 numbers, with further downward revisions for Indonesia (by -0.5ppt to 4.3%) and Malaysia (-0.5ppt to 6.5%).

EMDE Asia: GDP growth in 2020-22 (% YoY)

Latin America and the Caribbean (+4.6%; +3.1%) faced the deepest recession in 2020 across all regions (-7.0% vs -2.2% for EMDE on aggregate) but the IMF has turned more optimistic in the region in 2021. In the April report, the fund revised growth upwards by another 0.5ppt, bringing the cumulative upward revision to 1.0ppt since the October projections. Among the key economies, Argentina’s 2021 GDP growth has been revised upwards by 1.3ppt to 5.8% and that for Mexico by 0.7ppt to 5.0% (vs January). These offset the weak growth prospects for the tourism-dependent Caribbean economies (2.4% in 2021).

In Emerging Europe (+4.4%; +3.9%), Poland and Russia have seen a +0.8ppt upward revision (to 3.5% and 3.8%, respectively) albeit 2022 GDP growth projections have been reduced for both.

EMDE Europe / Latin America and the Caribbean: GDP growth in 2020-22 (% YoY)

The Middle East and Central Asia (+3.7%; +3.8%) and Sub-Saharan Africa (+3.4%; +4.0%) will see a more muted recovery in 2021. That said, both have seen upward revisions for 2021 which we can attribute to the oil price recovery and the quicker vaccine rollout in some places.

Among the larger economies, Nigeria (by +1.0ppt to 2.5%) and Saudi Arabia (+0.3ppt to 2.9%) are the beneficiaries. There’s also good news for South Africa where growth forecasts for 2021 and 2022 have been revised upwards (by +0.3ppt and +0.6ppt, respectively), albeit the absolute levels remain among the lowest among the larger EMDEs and medium-term growth prospects remain subdued at around 1.3% only.

Middle East and Central Asia / Sub-Saharan Africa: GDP growth in 2020-22 (% YoY)

With vaccines being rolled out and thanks to substantial forthcoming fiscal stimulus, the IMF’s growth prospects have gradually firmed up. However, with the above mainly driven by advanced economies and only some emerging and developing economies, this implies a highly uneven recovery. Compared to pre-pandemic projections, the cumulative per capita income loss over 2020-22 is equivalent to 20% of 2019 GDP per capita for EMDEs (excluding China) vs 11% for advanced economies. However, the divide is also visible within the EMDE space (e.g., strong growth in China and India vs muted recovery for ASEAN-5).

When it comes to risks to the outlook, they remain difficult to quantify and largely still relate to the pandemic, related restrictions and vaccine rollout (with both upside and downside risks). Given the recent rise in core rate yields, tighter financial conditions pose a noteworthy risk to the recovery.

The IMF thus dedicates a chapter to the spillover impact of monetary policy in advanced economies on financial conditions in emerging market economies. Higher US interest rates would likely be manageable for most emerging market economies if they are orderly and reflect stronger growth expectations, as in such a scenario, risk premiums on bonds tend to fall. Nonetheless, those with high fiscal and external vulnerabilities would remain at risk. However, a surprise tightening can trigger capital outflows that expose FX and debt financing-related vulnerabilities.

Growth for EM will revert to pre-pandemic average over the medium-term

Following a 2.2% GDP contraction in 2020, emerging market and developing economies (EM) are set to grow by 6.7% in 2021, mainly driven by India (12.5%) and China (8.4%).

Selected EMs: GDP growth in 2021-22 (% YoY)

Sorted highest to lowest in 2021

The growth levels in 2021 will however remain a one-off due to favourable base effects and catch-up growth. In subsequent years, GDP growth in emerging markets is set to fall from a high of 5.0% in 2022 to an average of 4.5% in the medium-term, roughly in line with median growth levels recorded in the five years prior to the pandemic.

However, below the surface, there are divergences. We note the IMF has become more optimistic on MENA/SSA and LATAM, with many countries set to embark on a higher growth path in 2021-25 (Y-axis in the chart below) vs 2015-19 (X-axis). In contrast, many CEE/CIS economies will remain in a lower gear (Azerbaijan, Belarus and Russia) or slow down somewhat (Hungary, Kazakhstan, Poland and Romania). EM Asia is weighed down by China’s structural slowdown (median growth of 5.4% in 2021-25 vs 6.9% in 2015-19) but remains in the lead.

On a country level, Argentina and Angola which faced recessions in the years preceding Covid-19 are seeing the largest improvements. The Dominican Republic and Ghana are set to slow the most but from high levels.

Median GDP growth in 2015-2019 vs 2021-2025 (% YoY)

Inflation pressure remain contained for most EMs

When it comes to inflation, the IMF expects temporary upward pressure and volatility driven by commodity prices but expects a return to its long-term average in its baseline projection, referring to weak labour markets and slack subsiding only gradually.

Higher inflation in 2021 is driven by advanced economies, where it is expected to rise from a low level of 0.7% in 2020 to 1.6% this year. For EMs, inflation is set to decline from 5.1% to 4.9% at the same time.

Selected EMs: Inflation in 2021-22 (% YoY)

In the medium-term, we note that inflation pressure is relatively contained for most emerging markets.

On a country level, Pakistan and the Dominican Republic see the largest upticks in projected median inflation in 2021-25 compared to 2015-19 (by around 2.0-3.0ppt). Double-digit inflation remains a policy constraint for Nigeria and Turkey. Meanwhile, Angola, Ukraine, Egypt and Ghana which have faced high inflation in recent years (and partially continue to do so) stand out for a much more benign inflation path going forward.

Inflation is lowest in more developed economies with strong fundamentals (e.g. Israel and Korea) or in those with pegs to the euro or dollar (e.g. Croatia, Ivory Coast, Morocco, Panama and some MENA countries).

Median CPI in 2015-2019 vs 2021-2025 (% YoY)

Current account balances remain favourable for larger EMs but normalise over the medium-term

The impact on current account balances from the pandemic has been more ambiguous as countries faced a collapse in exports and imports at the same time.

In 2020, current account balances deteriorated notably for countries dependent on commodity exports (e.g., Russia and GCC) and tourism (e.g., Croatia) but improved for many others (e.g., Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Philippines, Poland, South Africa and Ukraine). For the latter group, 2021 current account positions remain largely favourable amid the global recovery, but we should see a normalisation over the medium-term.

Selected EMs: C/A balance in 2021-22 (% YoY)

Sorted highest to lowest in 2021

Comparing median current account balances in 2015-19 vs projections for 2021-25, those in CEE/CIS are mostly expected to deteriorate while LATAM on balance is set for an improvement (albeit most countries will continue to run deficits). Oman, Jordan and Ethiopia see the biggest improvement but from fragile levels over 2015-19, while Tunisia will continue to run near-double digit deficits.

Among the regions, MENA also hosts the countries with the strongest surpluses in EM (Kuwait, Qatar and UAE). Thailand, Azerbaijan and Croatia see the largest deterioration, but the median for the former two will remain in a surplus.

Median C/A balance in 2015-2019 vs 2021-2025 (% of GDP)

Fiscal balance sheet vulnerabilities pose a concern for those with elevated deficits

The pandemic has wrecked fiscal accounts globally, driven by weaker growth and large deficits (lower tax and commodity revenues and higher spending to support the economy), which have led to a substantial jump in debt burden in 2020. Emerging market economies ran an aggregated fiscal deficit of 9.5% of GDP in 2020, with general government gross debt/GDP rising by 9ppt to 63%.

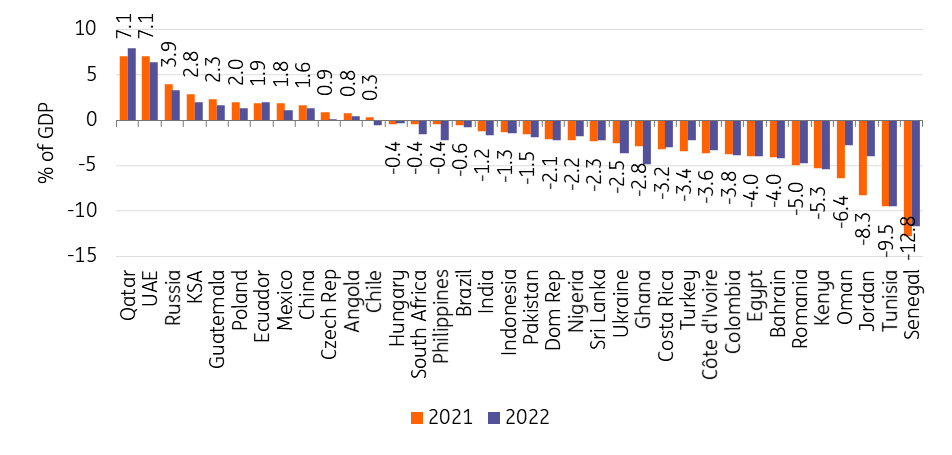

Selected EMs: Fiscal balance in 2021-22 (% YoY)

Sorted highest to lowest in 2021

Deficits will remain high in 2021 at 7.5% of GDP before gradually falling to 5% in the medium term. Thanks to the strong growth rebound, debt/GDP is expected to rise only modestly to 64% this year, but the IMF expects the ratio to surge above 70% by 2025.

Selected EMs: Government gross debt in 2025 vs 2020 (% of GDP)

Sorted highest to lowest in 2025

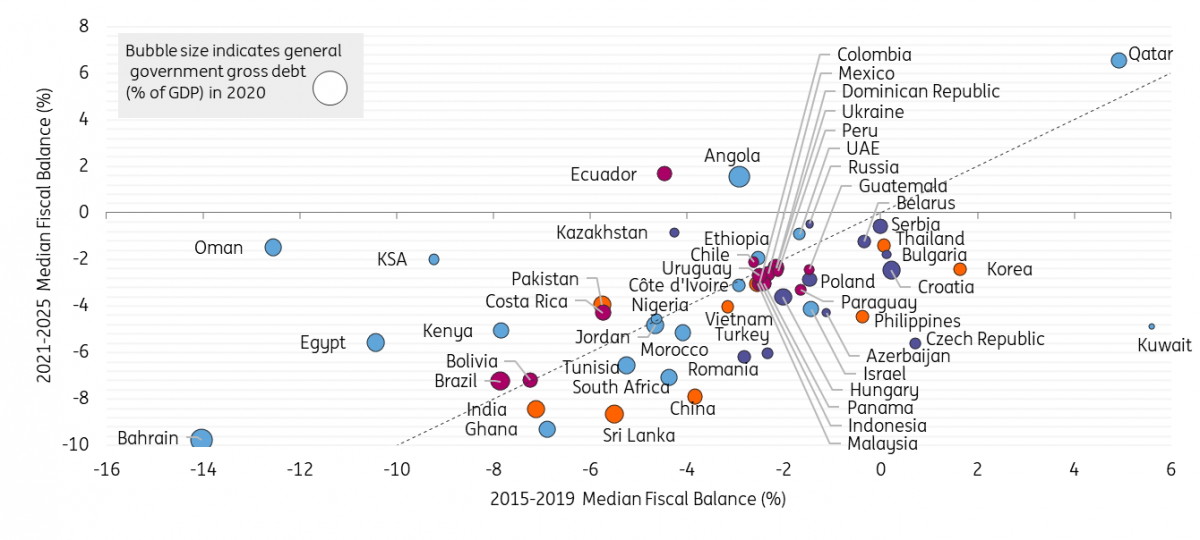

When it comes to the medium-term debt outlook for emerging market sovereigns, there is a large divergence, with extremes found in the MENA region.

Oman, Saudi Arabia and Egypt ran large fiscal deficits in the pre-pandemic years but are expected to see the largest improvements (notably Oman’s median fiscal balance improves by 11ppt in 2021-25 vs 2015-19). However, deficits remain very wide for Bahrain, pushing government gross debt to 148% of GDP in 2025 (vs 133% in 2020). Meanwhile, Kuwait’s fiscal surplus in 2015-19 is set to turn into a large deficit in 2021-25.

We are most concerned about countries that have already elevated government gross debt/GDP ratios to begin with and run large deficits going forward

We are most concerned about countries with already elevated government gross debt/GDP ratios, beginning with and running large deficits in the future. Among the larger economies, South Africa’s fiscal outlook remains most concerning, as wider deficits (median of 7.1% of GDP over 2021-25) will see a continuous rise in debt/GDP by 16ppt to 93% in 2025. In contrast, Brazil’s gross debt/GDP ratio is expected to stabilise at just around 100%. Among the frontier market countries, Bahrain (as highlighted above), Sri Lanka (debt/GDP seen rising from 100% in 2020 to 107% in 2025), Tunisia (88% to 100%) and Ghana (78% to 87%) are the lowlights.

In contrast, Angola is expected to run fiscal surpluses, which will see debt/GDP falling by more than 50ppt to 74% by 2025.

Median fiscal balance in 2015-2019 vs 2021-2025 and government gross debt in 2020 (% of GDP)

With debt levels rising for many governments, so will interest expenditures going forward.

Below, we look at interest expenditure as a percentage of government revenues and note that those are increasing, especially in places where those ratios had been high before the pandemic already. Notably, in Sri Lanka and Ghana, interest expenditure is expected to eat up around 60% of government revenues each year on average over 2021-25 (i.e., 20ppt higher than over 2015-19). They are also on the rise in some GCC countries as those governments have turned to debt capital markets since 2016 but pose less concern (except for Bahrain).

The rise in debt costs is also worrisome as it inhibits governments from providing additional fiscal support despite Covid-19 still posing a substantial challenge in 2021 and beyond. Notably, Angola, Costa Rica, Egypt and Pakistan are among the countries weighed down by elevated interest expenditure and have to compensate with primary surpluses in the medium-term (averaging between 1.0% of GDP in Costa Rica to 6.4% in Angola annually over 2021-25).

Median interest expenditure in 2015-2019 vs 2021-2025 (% of government revenues)

Appendix: List of selected countries included in assessment and charts

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article