How Europe’s housing scarcity varies across countries

The scarcity of affordable housing is a shared problem across Europe, despite fundamental differences between housing systems. This harms the well-being of citizens and could curb economic growth. We find that housing scarcity is expressed in different ways across Europe

Local housing markets across Europe are fundamentally different and difficult to compare. Variations in fiscal policies and the supply of social housing are just some of the many differences. But in this article, we aim to analyse the severity of the housing scarcity across the 10 biggest EU countries.

We use six indicators to compare the housing situation. The first three provide insight into the current housing situation of households: the age at which young adults leave their parental home, living space per person and the relative cost of housing. The next three indicators provide insight into the (future) housing challenge of countries, and how easy it is to achieve this. We look at expected population developments, population density and the historic rate of new-build houses.

Germany, Italy and the Netherlands show higher levels of housing scarcity

Germany, Italy and the Netherlands show higher levels of housing scarcity in many of the criteria we used. For instance, in Italy, young people have enormous difficulty finding their own place to live and Italians have fewer rooms at their disposal in general. However, the affordability of total housing costs in Italy is one of the best relatively speaking. In contrast, in the Netherlands and Germany, the affordability of living is problematic and the population density is high, which makes further expansion of the housing stock more challenging. That said, in the Netherlands and Germany, people are relatively young when they leave their parental house. This means that despite all the housing market issues, one way or another, many of them are still able to find a place of their own.

Sweden and Ireland have lower levels of scarcity

At the other end of the spectrum, we often find Sweden and Ireland. Housing scarcity also exists in these countries but to a lesser extent based on the criteria we used. In Ireland, housing costs are relatively low, the Irish have relatively more rooms at their disposal and population density is relatively low. Yet over the coming decades, Ireland's population growth is expected to be the highest in Europe, which could put extra pressure on the market. Swedes are the youngest when they leave their parental house. This means that, although it is probably not always easy, they are able to find their own place to live. Low population density and a high rate of new-build houses suggest the Swedish housing market could adapt relatively easily to further population growth. Yet, the Swedish housing market also has its issues, as affordability is one of the worst.

Implications of housing scarcity

Most European housing markets have to deal with scarcity. Yet a decent and affordable place to live is one of the most important factors for well-being. What's more, it is important for economic growth as housing scarcity limits (national) labour mobility. If local young people and newcomers have trouble finding a decent and inexpensive place to live in one region, they may choose to look in another, which could cap growth in that area.

Therefore, many countries are trying to boost the supply of new houses. For instance, the German government has set a target of building 400,000 houses a year and the Dutch government aims to build 100,000 new houses every year. However, governments often miss their goals for cyclical reasons (such as increased interest rates and higher building costs) and structural reasons (such as protracted building procedures and/or shortages of suitable building land).

Below we discuss the six indicators in turn:

Age children leave parental house

Young people are most affected by the scarcity of homes. This means they often have to stay at their parents' house for longer than they would like. The age that young people leave their parents' house gives an indication as to how difficult it is for them to enter the housing market though, of course, other factors (for example cultural preferences and unemployment rates) also play a role here.

Italian & Spanish youths leave their parents’ home the latest

Average age of young people leaving the parental household (2018-2022)

Italian and Spanish young people live the longest with their parents

What we see is that in the Southern European countries of Spain and Italy, children are the oldest when leaving their parents' house. In both countries, young people are, on average, (almost) over 30 years old when they find their own place to live for the first time. Of course, it could also be the case that this has to do with economic circumstances (eg high youth unemployment), culture and personal local preferences.

Young Swedes, meanwhile, leave their parents' house more than 10 years earlier, on average. Also, in the Netherlands, France and Germany they are, on average, a lot younger at approximately 23 years of age when they move away from their parents. Although housing scarcity is also seen as high in these countries, young people have less difficulty finding their own place to live.

Living space per person

A second indicator for measuring the scarcity of housing is average living space. Living with many people in a house and not having ample living space might be considered suboptimal for most people. Therefore, the available square meters of living space and the number of rooms available per person are important. In this analysis, we use the measurement of the average number of rooms available per person for two reasons: this data is better registered and we assume people prefer to live in a smaller private room instead of sharing a larger room with a roommate.

Most people per room in Poland, least in Belgium, Ireland and the Netherlands

Average number of rooms per person, 2022

Most cramped housing situation in Poland

We find that the Polish have the fewest rooms at their disposal. They have on average only 1.1 rooms per person. Italians and Austrians follow with 1.4 and 1.6 rooms on average per person. At the other end of the spectrum, we find Belgium, Ireland and the Netherlands. Inhabitants of these countries have, on average, a little more than two rooms per person at their disposal.

Overcrowded rate

The rate of overcrowding also depends on the composition of a household. For instance, a couple could live in a one-room apartment, however, when they are not a couple it’s seen as (and is) overcrowded. Eurostat calculates this overcrowded rate. Here, we find approximately the same picture. Italy and Poland have the most people that live in an overcrowded house and Belgium, Ireland and the Netherlands have the fewest.

Overcrowding rate lowest in the Netherlands, highest in Poland

Overcrowding rate: % of people residing in a house with insufficient number of rooms, 2022

An interesting observation is that in these three less overcrowded countries, the rate has increased slightly in the last decade. However, in Poland, it has decreased significantly by more than 10 percentage points during the same period. As a result, the Dutch, Belgians and Irish may feel that the situation is deteriorating, albeit marginally. Nevertheless, when compared to other countries, they still reside in relatively spacious homes.

House affordability

House and rent prices say a lot about the scarcity of houses. Prices go up when supply is limited and demand is high. However, just comparing house prices among countries doesn’t tell the whole story. There are many local circumstances that influence price levels, as disposable incomes and housing tax regulations differ. This affects what households are able to pay for living costs. To take this into account, we use the share of total housing costs (including utilities) in total disposable household income.

Highest relative housing costs in Germany, lowest in Ireland and Italy

Median of the distribution of the share of total housing costs in the total disposable household income, 2022

Worst affordability in the Netherlands, Sweden and Germany

German and, to a lesser extent, Swedish and Dutch households are the worst off when it comes to housing costs. A median household in these countries pays more than 16% of their disposable income on living costs. This makes the burden of housing relatively high. A further dive into the figures shows that in Germany, the housing cost burden is relatively equally divided among homeowners and tenants. In the Netherlands, there are huge differences. The median Dutch homeowner pays less than 5% of their disposable income on living costs (due to a generous mortgage rate tax deduction) while the median tenant (especially in the liberalised market) pays more than 40% of his disposable income on living.

Expected population developments

So far, we have only discussed the current situation. However, future developments will affect the scarcity of homes as well. An important factor is population growth. A growing population will put more pressure on the housing market.

Highest population growth expected in Ireland and Sweden

Baseline population developments (Index 2022=100)

Highest expected population growth in Ireland and Sweden

Population projections show that Ireland and Sweden have the highest expected population growth. In both countries, the number of inhabitants is expected to increase by more than 10% in the next two decades. High (expected) life expectancy and high fertility rates in these countries are the main drivers. In Ireland and Sweden, live births are the highest in the EU at 1.6 and 1.7, respectively. Only in France is the fertility rate higher at 1.8. However, net expected real migration is lower in France. For Sweden, a relatively high migration figure is also driving up the expected population growth.

At the other end of the spectrum, we find Poland and Italy with an expected decline in the number of residents. The main reason is that they face lower fertility rates. In addition, Poland’s net migration is likely to be negative as the recent influx of Ukrainian refugees is expected to gradually return in the coming years.

Population density

Another important indicator of housing scarcity is how many people live in a country relative to the size of that state. When a nation is densely inhabited, it has less space to build new houses. Nevertheless, it is not always so straightforward as it is not possible to build everywhere. For instance, Austria has many inhospitable mountain areas where development is difficult or even impossible. Sweden, with its dense forests, faces similar issues. For environmental reasons, it is not always desirable to build there and local and EC regulations increasingly discourage this. In addition, not all areas are suitable for new development as they are too far away from economic activity (eg. job opportunities) and important facilities (eg. schools and hospitals). That said, we still think population density can be one of the indicators to measure the scarcity of a housing market.

Belgium and the Netherlands most populous

Population density: Number of inhabitants per km2

Most inhabitants per km2 in Belgium and the Netherlands, least in Sweden and Ireland

When we categorise the 10 largest EU countries, we find that the Low Countries have the highest density per square kilometre. Almost 500 Dutch people and almost 400 Belgians live on one square kilometre, on average. In Sweden, this density is more than 20 times lower, with less than 25 Swedes sharing one square kilometre on average. Additionally, Ireland and Spain rank among the top three most spacious countries. One can imagine that new housing developments are much more difficult in the Low Countries when so many people are already living there.

Rate of new build houses

The final indicator we use is the rate of new-build houses in the last decade as a percentage of the total housing stock. Like all other indicators, it is not perfect, but it could say something about the potential for new developments. When this rate is high, it may be a sign that the country has relatively fewer hurdles (eg. the availability of land for building, dealing with permits, complying with all required notifications and the availability of financing) for new housing projects. The caveat with this gauge is that it focuses on the supply side. When demand is low, this could also result in low supply of new houses. Yet, as most housing markets cope with shortages, supply constraints are therefore dominant and therefore we think this is still a relevant indicator.

Fastest growth of housing stock in Poland

Average yearly new housing completions as a % of total housing stock

High percentage of developments in Poland and Austria, low in Spain and Italy

Poland has added the highest percentage of new residences to its stock in the last decade. In the period 2020-2022, the Polish housing stock increased by almost 1.5% yearly. Austria and Sweden also showed high yearly rates of new houses. These relatively high rates make it possible to deal better with the scarcity of houses as a high rate of new supply can lower shortages. At the other end of the range, we find the Southern European countries of Italy and Spain. The rate of new houses is low (below 0.3% yearly). This could be due to many issues such as long permit procedures or financial shortcomings. Nevertheless, it keeps the local housing markets in Spain and Italy scarce.

Housing scarcity characteristics differ enormously among countries

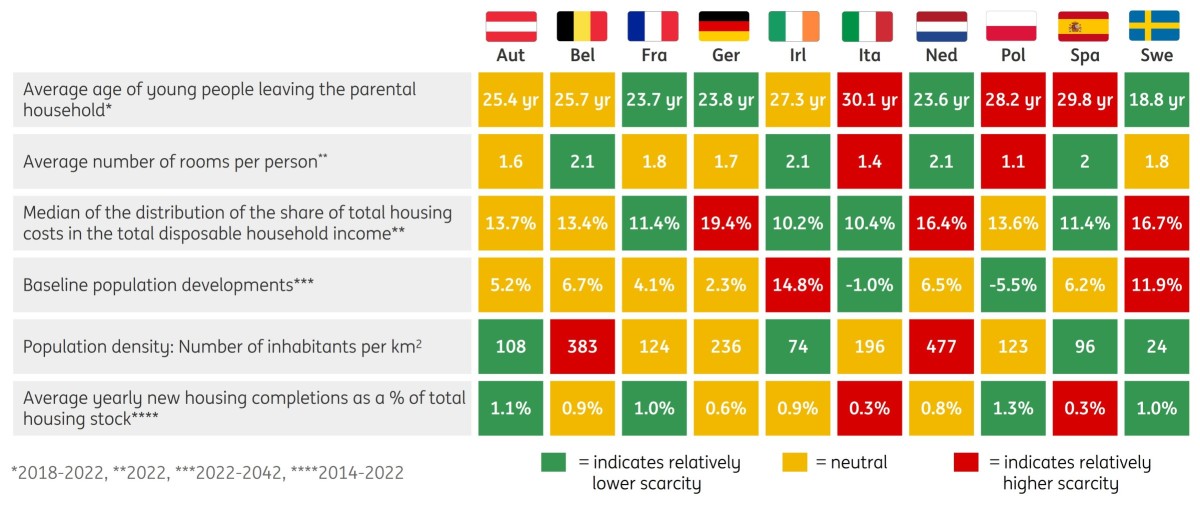

Overview of used housing scarcity indicators

Enormous variations in the type of housing scarcity

All in all, we conclude that almost all EU countries have their unique issues. It is therefore impossible to say which country has the worst or best housing market. In some countries, young people have enormous problems finding a place to live, in others, the affordability of a house is bad. In still others, many households are overcrowded as they don’t have enough rooms at their disposal. Extending the housing stock with new houses could be a good solution to make housing less scarce. However, the rate of new construction varies enormously among countries.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article