How Asia has managed to keep rates low in the face of rising inflation

Central banks in Asia are not hiking interest rates aggressively, whereas their Central and Eastern European peers are. So why aren't we seeing crazy Asian rates?

| 0.065% |

Average change in policy rates for Asia-10*CE3 = 2.5% |

*What is Asia 10?

Asia 10: China, HK, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan, and Thailand

CE3 = Hungary, Czech Republic, Poland

(Simple average of cumulative policy rate changes, calculated from Jan 2021)

Cumulative policy rate changes

Rates sharply up in CE3, but mainly flat in Asia

In Central and Eastern Europe, rising inflation against the backdrop of re-opening economies and supply constraints has led to central banks aggressively hiking policy interest rates. Policy rates in Poland, for example, are up 215bp from their pandemic low of 0.1% to meet an inflation rate of 8.6% Year-on-Year. Hungary’s one-week deposit rate has been raised 310bp to 4.0% in the face of inflation rising to 7.4%, and rates are 225bp higher in the Czech Republic as inflation has surged to 6.6%YoY.

This experience is not on the whole being mirrored in Asia. Where rates have gone up (in New Zealand, South Korea) they have gone up much less rapidly. And where they have not yet increased, central banks are often still hanging on to a stance of "growth support" and taking their time to shift to normalisation. In one important case – China – key policy rates are being cut, not raised.

So what's going on? What explains this divergence in policy between these two regions?

The economy, stupid!

In very general terms, the main reasons why any Asian economy might want to aggressively raise rates are simply not present. Namely:

- Inflation – Asian Inflation is reasonably well behaved. There are some exceptions to this, but generally, inflation is not a big problem.

- Currencies are also fairly well-behaved – there has been some modest weakness vs the US dollar, but not much. In the case of China, the Chinese yuan has actually appeared to decouple from euro/US dollar movements thanks to enhanced capital inflows. There’s consequently no blanket requirement for regional central banks in Asia to support currencies with higher rates.

- And current accounts are more balanced than they were. This is generally a strong current account surplus region anyway with floating exchange rates. But even where the external balance has historically been in deficit, the pandemic has tended to restore balance, and there is little need to squeeze domestic demand any harder on this account through higher rates.

Let's look at these reasons in more detail.

Inflation

The principal difference between Asia and the CE3 is inflation. Inflation rates across the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region are elevated, but that is mostly because they come off a very low base. Where there is inflation, it tends to be imported, or supply-shock-driven – usually food, some energy too right now with crude oil in the mid-to-high $80s.

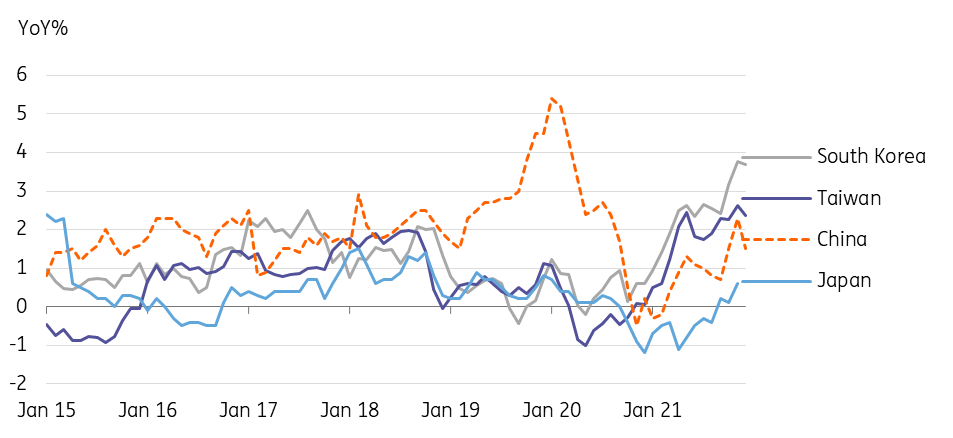

For example, in North Asia, South Korea stands out as having inflation that is higher than the prevailing range of the previous five years, though at 3.7% it already looks as if it may have peaked. China has seen some inflation, particularly in wholesale prices for energy after President Xi Jinping’s push on environmental clean-up led to shortages of electricity as coal-powered plants were shuttered. But a rapid back-pedalling of some of these restrictions has managed to contain these pipeline pressures, and the latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) release for China actually showed a decline of CPI inflation to only 1.5%YoY from 2.35% in November.

Japanese inflation is also higher than normal, but it is still only 0.6%YoY, and even though it will likely rise a little further in the short-term, this is principally a function of food and energy costs – core inflation remains buried deep in negative territory. The Bank Of Japan has just met and left policy on hold – rates remain essentially zero or slightly negative here.

North Asia inflation

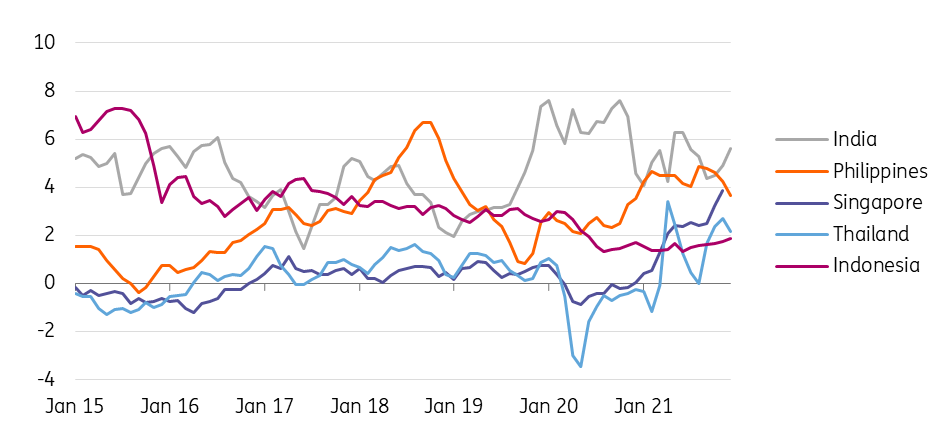

In South and South-East Asia, inflation in both India and the Philippines is a bit on the high side, although neither looks particularly out of place compared to prior trends, and both register inflation that is lower than at other times during this pandemic.

Supply-driven increases such as those exhibited by the Philippines and India come and go. The Philippines has had very damaging Typhoons recently. These will have damaged agriculture and pushed up fresh food prices when data is released in the coming months. But the reduction of tariffs on rice imports means that such negative supply shocks and their effects on price levels are likely to be short-lived, though this will also pressure the trade balance in the short term.

India’s latest 5.6%YoY inflation print for December was mostly due to a very sharp drop in food prices a year ago. Food prices in India had spiked up recently, but have already started to moderate. And after a further month of expected inflation increase in January, they should start falling back towards the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) 4% +/-2% target range over the rest of the year, taking pressure off the central bank to react with higher rates.

Inflation in both Thailand and Indonesia has risen, but from such low starting points that neither poses much threat to current policy rates. Singapore inflation at 3.8%YoY in contrast has risen well above previous trends and will likely trigger a tightening of policy through the Nominal Effective Exchange Rate (NEER) path when the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) holds its next meeting in April. This will probably drag up short-dated market rates for the island state, though, at the moment, the three-month Singapore Interbank Offered Rate (SIBOR) remains very steady at about 0.43%.

Elsewhere in the APAC region, market expectations for rate hikes in Australia have priced in some aggressive tightening this year, but are in stark contrast to the message from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), which is touting a path of near-term stability. Australian inflation dipped from its 3.8% 2Q21 peak to just 3.0%YoY in 3Q21 and looks as if it will remain at about 3% in 4Q21 (plus or minus the odd tenth of a per cent). That could see markets re-evaluate their hawkish positioning in bank bill futures. That said, you might be able to make a case that across the APAC region as a whole, it is the more developed economies that arguably seem to be seeing the largest increases in inflation.

South and South-East Asian inflation (YoY%)

Policy response – not much so far

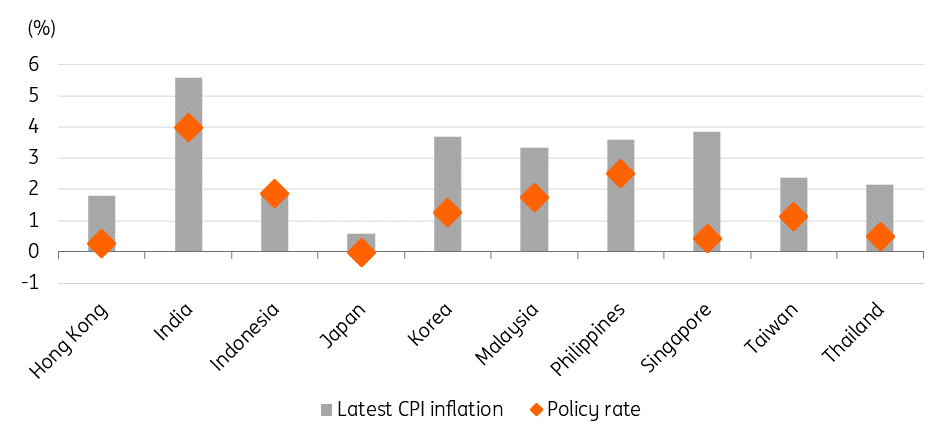

Inflation across the region right now is typically higher than policy rates which is a simple way of saying that there are negative real policy rates right now (though properly calculated, this uses inflation expectations, not the actual current inflation rate). In normal times, this would warrant a policy tightening to bring inflation back under control. But with much of the overshoot reflecting base effects and one-off supply shocks, central banks can afford to be relaxed at the moment.

Even in the developed economies, where we see more of an impact, the inflation picture looks sufficiently benign that central banks will be able to address rising prices through more gradual tightening. Korea is a good case in point. The Bank of Korea (BoK), one of the most hawkish central banks in the APAC region had been steadily pushing the policy repo rate higher since late August 2021. Headline inflation in Korea is 3.7%YoY, but even so, a January 25bp rate hike to 1.25% looked a bit aggressive against the backdrop of a Covid wave (now slowing) and an upward spike in the unemployment rate as movement restrictions slowed the economy. Korea’s heavily indebted household sector means it probably won’t take too much tightening to suck the wind out of the sails of the Korean consumer sector and its frothy residential property market. And Korean rates will probably peak lower relative to prior cycles.

Moreover, BoK Governor, Lee Ju-Yeol, steps down in March, and there may be no replacement of this position until May/June due to the presidential election. So we may not see much more from the BoK until later this year unless they opt to implement another hike before the end of the first quarter. The January hike may itself have been brought forward due to the possibility of a leadership vacuum in 2Q22.

"Real" policy rates in Asia mostly negative

Why is inflation in Asia not higher?

- During the worst of the pandemic, much of Asia did not have to resort to national lockdowns, and as a result, this did not lead to the big switch from services to goods experienced elsewhere that has found capacity insufficient.

- Re-opening has also been more gradual, less binary than it has been in the West, and this has not resulted in the scale of demand shocks on re-opening that have been seen elsewhere.

- Inflation is often dominated by food costs rather than services and these prices while inherently volatile, have been less affected by the pandemic.

- Some supply chain issues may originate in Asia (semiconductors), but the ramifications of shortages are typically downstream and away from Asia – e.g. while chip production is scaled up, the lion’s share of shipments remains in Asia.

- Freight rate spikes are much more pronounced between Asia to US, and Asia to Europe than Asia to Asia or US/Europe to Asia. And where there are supply chain disruptions, there is a greater array of alternative suppliers locally, thanks to diversification away from China in recent years due to its trade war with the US. Ironically, that’s a positive spillover from the trade war that was at the time thought to be inflationary.

- One factor that can't be blamed for the inflation divergence is high natural gas prices, where consumption per capita is not markedly different between Asia and Europe.

Freight rates not such a big deal for Asia

Currencies – its not all about the dollar...

Although there was some generalised weakness of Asian currencies against a resurgent US dollar during the second half of last year, Asian currencies have more recently paid far more attention to the local currency giant, China's yuan, than the more geographically distant US dollar. As the local "centre of gravity” as far as Asian currencies are concerned, the Chinese yuan's stability/strength provides quite a bit of support for the "satellite" currencies of the region. And this is one reason we believe that other Asian exchange rates have been fairly resilient to generalised US dollar strength.

As China embarks on a round of monetary easing, and with its markets struggling with the workout of the property development sector, this strength could come under some pressure. However, while the Chinese yuan is more market-driven than it once was, it is far from a free float, and we believe the authorities in China are reasonably happy to accommodate a firm yuan as it helps choke off imported inflation – something that would not sit well with President Xi's common prosperity drive.

In the emerging market space, Asian currencies that you would normally expect to show weakness in the face of an aggressive US rate hike cycle and weakening global market sentiment, have held up remarkably well. Indonesia’s currency, the rupiah (IDR), for example, has been quite stable. Admittedly, Bank Indonesia (BI), the central bank, has engaged in market smoothing for both the currency and the bond market. But while purists may not like an artificially stabilised currency, that stability has itself been somewhat self-fulfilling in that large gyrations are no longer expected by market participants. Indeed, Indonesia was one of the top picks for the EMTA SE Asia seminar that ING hosted in November, well-liked by panellists and participants.

The Philippine peso has been under a bit more selling pressure. Last year, Fitch highlighted the “scarring” caused by Covid as potentially weighing on Philippine potential growth and as a reason for their negative outlook. This could hamper government revenue-raising efforts and may result in a downgrade this year if growth disappoints. Though from BBB to BBB- this would still leave the Philippines investment grade. S&P and Moody’s both have a stable outlook.

India has had a choppy time with its currency. On the one hand, a buoyant IPO pipeline has led to capital inflows to equity markets. But this has looked a bit speculative. The money flows keep waxing and waning causing the Indian rupee to whip around but has undoubtedly been supportive at times. The trend still looks slightly negative for the rupee, but it could get a big shot in the arm from inclusion into global bond indices this year, and this could take place as early as 2Q22. Broker estimates estimate foreign inflows into Indian markets at $40-50bn if this happens.

But generally, don’t underestimate China’s stabilising influence on currencies and therefore rates in the rest of the region. It’s not all about the US dollar these days.

CNY decoupling from EUR/USD

External balances – generally strong

Most of Asia runs significant current account surpluses. But one of the “benefits” of the pandemic was that the perennial deficit countries of the region (Philippines, Indonesia, India) saw their current account balances shift out of deficit and even register small surpluses. As these economies recover, this is reversing, though with the exception of the Philippines, which has just recorded a large trade deficit. This not looking too alarming yet.

India too is recording a large external trade deficit, though while capital inflows remain strong, this isn’t a substantial problem. The worry will be if these portfolio flows dry up – which they might. But it is very hard to say when (they could be a victim of Fed tightening drying up flows to emerging markets, but then again, maybe not...).

Indonesia continues to run a very healthy-looking trade surplus along with its low inflation success. This will most likely shrink this year, but it looks well-positioned to start the year.

Current accounts still OK

Rates will rise in Asia, but not rapidly and maybe not everywhere

We do expect to see some increase in rates from the Philippine Central Bank (BSP) as its inflation has been hovering just the wrong side of the inflation target’s upper bound. From his recent comments, BSP Governor, Benjamin Diokno, sounds like he’s inclined to keep rates untouched even in the face of the Fed rate hikes. We doubt that he can keep that stance indefinitely, but a possible adjustment from him this year could mean just 50-75bp of tightening. This would be way off what the CE3 has seen and leave Philippine policy rates far from “crazy-increase” territory.

And it is a similar story for Indonesia. Bank Indonesia Governor, Perry Warjiyo, has sounded fairly dovish, though more recently, has hinted at possible modest rate hikes by the end of this year, and begun to remove liquidity support with an increase in bank reserve requirements. So once again, higher, but not “crazy" territory.

India is another likely hiker and is also struggling to keep inflation within its target range, and as a result, we also expect them to hike later this quarter. But the repo rate at 4% now will probably not go much higher than 4.6% by the end of this year. The RBI remains fixated on growth support and a new wave of Covid could delay the start of any normalisation.

Korea was one of the first hikers out of the blocks in APAC. Inflation is on the high side here at about 3.7%, but a long way off US or European levels and this is probably the peak. The BoK will hike again this year, but we don’t think it will take much to subdue borrowing and spending. A peak in rates of 1.75%, perhaps?

In Australia, we doubt the RBA will hold rates steady for as long as they seem to suggest in their various statements and releases. But there is still a chance that they will not start raising rates until 2023. If they do start this year, it will probably be no more than a solitary 25bp towards the end of the year.

Japan hasn't tightened policy rates in any meaningful fashion for longer than we can remember. A short term bounce of inflation above zero is not, in our view, a sufficient reason for any change to their rate policy, though we could envisage a slowing of their asset purchases which haven't looked like a binding policy constraint for years.

And in China, the impact of the zero-covid policy and regulatory blast that has hit sectors from energy to education, and most notably property development in recent months, is weighing on growth to the extent that the People's Bank of China has been cutting rates since mid-December, and cut again in January. We anticipate more rate cuts over the coming weeks and possible months as well as additional reductions of the Reserve Rate Requirement (RRR).

Asian policy rates forecasts

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article