Asia’s lamentable green Covid-19 response

The Covid-19 crisis has offered governments around the world an opportunity for a total rethink on how their economies will operate in the decades to come. Few governments in the Asia-Pacific region appear to have grasped this chance, with most choosing easier, but arguably less effective traditional stimulus approaches. Download the full report here

The environmental impact of Covid-19

With most of our economies likely to look very different when we finally emerge from social distancing, this is being seen by some countries and regions as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to lock in these environmental gains. The fiscal rule books have been ripped up, and cost can no longer be cited as an excuse for inaction. This isn’t quite a clean slate for a total rethink of our economies, but it is probably the closest thing to that we will ever get.

A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity

Regions such as the European Union, are using the pandemic as an opportunity to press the restart button on their economies and to focus hard on the environment. The UK too seems to be reinventing some green credentials and is also increasing its stimulus to measures concerned with energy efficiency. But is the same true for the Asia Pacific region? Is Asia reaching for the environment reset button too?

The short answer to that question, which we shall address in detail shortly, appears, disappointingly, to be a resounding “no”. And this is particularly disappointing when you consider the big role Asia-Pacific plays in greenhouse gas emissions and global warming.

Total CO2 emissions vs Renewables as % of total primary energy consumption (2018)

Asia state of play

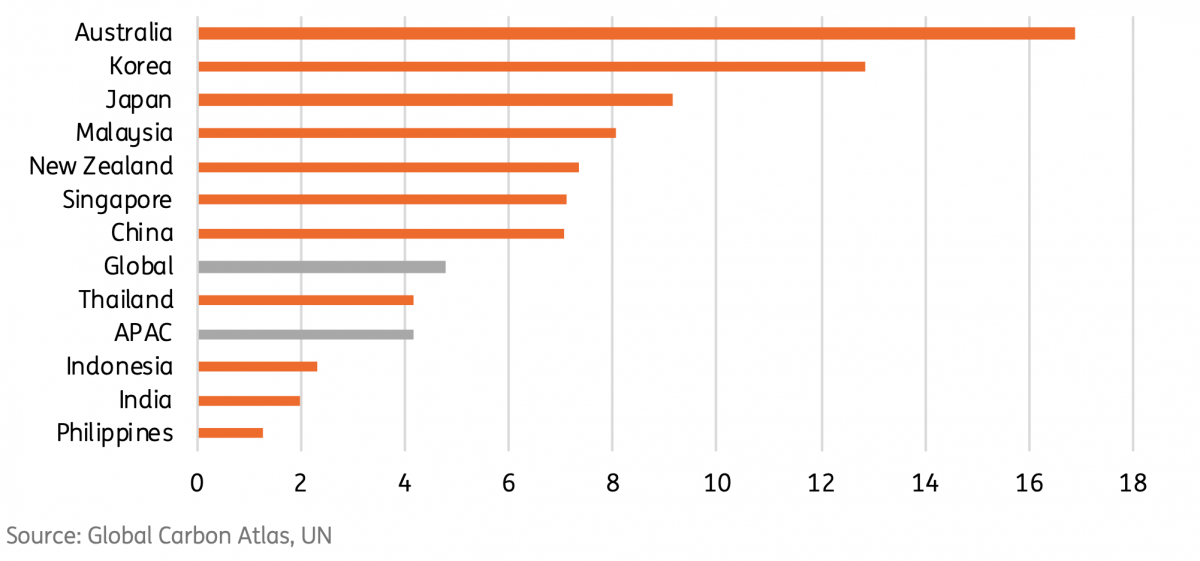

The APAC region is a substantial carbon emitter, making up around 47% of total global emissions. It really is no surprise that China is the main contributor, making up around 58% of the APAC total, or almost 28% of total global emissions. For comparison, the US contributes 15% to total emissions, whilst the EU’s share is a mere 9%. Since 2000, carbon emissions from the APAC region have grown by 125% (China’s emissions over the period have grown by about 200%), while over the same period US and EU emissions have declined by 10% and 18% respectively.

It is always going to be a difficult task for developed countries, which have already passed their peak industrialisation phase to persuade emerging economies to cut their emissions when these economies are focused on growth. On top of which, the low price environment we are currently seeing in fossil fuels will do little to push these emerging economies towards meaningful green policies.

Climate targets reached and missed

However, saying that, a number of countries within APAC have agreed on some target reductions. This includes the Copenhagen Accord, where participating countries agreed to reach certain emission targets by 2020. The results of this have been mixed for the region and for the vast majority of Asian countries participating, their target was more focused on reducing carbon intensity or reducing carbon emissions from “business as usual” (BAU) projections. Therefore, overall emissions from these countries are still clearly trending higher. But the likes of China and India have hit their targets, and have done so ahead of schedule.

China has managed to reduce carbon emission intensity by 40-45% from 2005 levels, whilst India reduced emission intensity by 20-25% from 2005 levels. Australia, New Zealand and Japan all pledged to reduce overall emissions by 2020, and unfortunately with the exception of Japan, it looks as if they will miss these targets. Australia was initially on track, with a carbon tax that was introduced in 2011, however, this was repealed in 2014, which has not helped. As for the Paris Agreement, it is yet to be seen how countries in the region will perform.

Are nationally determined contributions from countries ambitious enough?

Under current policies, the UN expects that of G20 members in the region, only China and India will achieve their 2030 targets, whilst Australia, Japan, South Korea and Indonesia will need additional policies to reach their targets. In addition, there are questions around whether the nationally determined contributions from countries are ambitious enough, with many of them falling short of the share that would be needed so that collectively, global warming limits are achieved. Therefore in the absence of more aggressive targets, we will need to see deeper cuts from other regions in order to meet the 1.5 degree Celsius increase target agreed under the Paris Agreement.

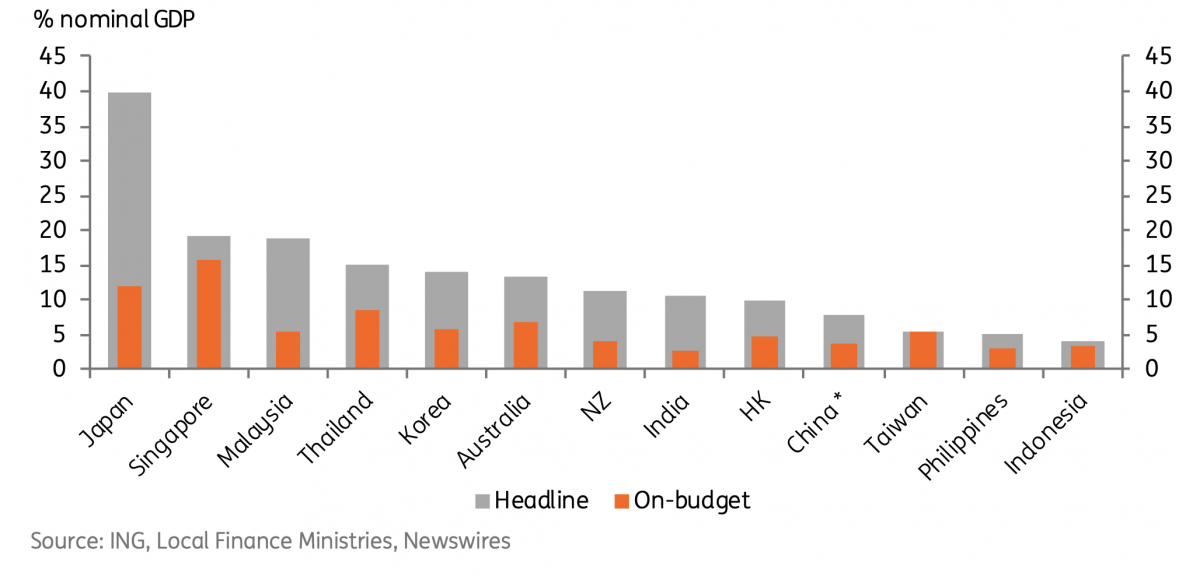

Fiscal packages – claimed and “real” (on-budget)

Fiscal spending has been substantial

Setting the stage for some potential shift of government focus on the environment, fiscal stimulus plans in the APAC region have been huge. The convention in this part of the world is to throw the kitchen sink into official estimates of the scale of stimulus. Exactly why this is done is not clear, as it must be pretty obvious to most people that counting figures already included in previous budgets, soft loans and funds that will never be drawn or grants that will never be disbursed is not likely to provide much in the way of stimulus.

In the chart above, we show the difference between “on-balance sheet” spending figures, which we can reliably assume will make it into the economy and provide some support, and the myriad of other measures, which in all likelihood, largely won’t, but which do boost the headline. Japan takes the gold medal for implausibly large support claims. But even their on-balance sheet figures probably won’t all see the light of day in the 2020/21 period, and we would be extremely surprised if this significantly nudges the needle on Japan’s perennially soft GDP growth.

How much of this spending can be described as green?

Others, notably Australia, New Zealand and Singapore are employing a lot more “real” support. And while this still probably won’t lead to stellar growth, it will provide some insurance that there is at least an economy left to recover when Covid-19 is finally brought under control. But how much, if any, of this spending can be described as green? Has the world’s largest emitting region, Asia-Pacific (50% of total global CO2 emissions), taken a leaf out of the world’s greenest region, Europe (12%) ? Or is it back to business as usual?

Per capita CO2 emissions (2018)

Reasons why Asia has not acted

That the near absence of any green policies in Asia’s Covid-stimulus packages is a missed opportunity is one thing, it is doubly disappointing given how important Asia- Pacific is for global greenhouse gas emissions. This was an opportunity not just to catch up with other regions, but to restore trajectories towards Paris Agreement objectives. Instead, several countries in our region have taken decisions which lock themselves into a trajectory of even higher greenhouse gas emissions from which it will be even harder to back-pedal.

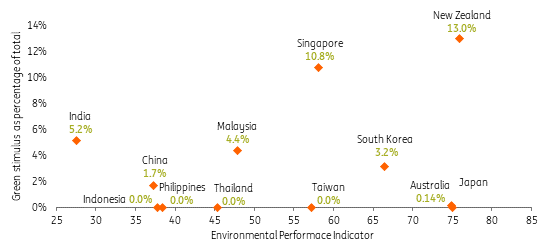

The chart below shows green stimulus as a % of total Covid-19 stimulus measures, plotted against their Environmental Performance Index. For a disappointing number of countries, their marker has not even risen off the X-axis. It looks as if the poorer the EPI, the less effort has been made to improve conditions with Covid-19 stimulus – whereas those with better scores continue to make more efforts. For environmental targets to be achieved globally, we need to see this chart deliver the opposite slope.

Environmental Performance Indicator and green spending as a percentage of total Covid-19 stimulus

The power of green stimuli

One or two countries were already placing more stress on the environment before the pandemic (India, China), and the dearth of specifically green policies in their Covid-19 stimulus packages can be partly explained via a background of general environmental progress. But while there is undoubtedly some truth in this, you could also make this argument for Europe, and they have not shirked from a much bolder environmental push. Indeed, to many, this will sound a fairly hollow excuse. Others may not explicitly be embarking on environmentally harmful stimulus policies themselves, but are continuing to fund these overseas.

This is a particular trait of some of Asia’s richer countries (e.g. Japan) which are continuing to fund coal-fuelled electricity generation capacity in developing nations as they look for a quick, and quite literally dirty boost to the economy. Others have talked up their green credentials while delivering relatively little in terms of actual spending (South Korea falls into this camp). Only New Zealand comes out of this analysis looking like it has enhanced its green credentials to any extent. Singapore may possibly also come out on the positive side of the ledger.

There don’t seem to be any clear reasons why countries in Asia-Pacific have not taken a greener route to Covid-19 stimulus. A lack of imagination enhanced by lower cultural weights placed on environmental sustainability than on economic growth and wealth creation probably explains part of this outcome. That said, research suggests that in many if not most cases, green stimuli can deliver a stronger boost to the economy than other policies, and generate a greater number of jobs. So if this is the reason, it may well be a misguided one.

Download the full report

You can download our full report here.

From China to Japan, India, Thailand, Australia, Malaysia and beyond, we look at where we stand, what 'green' measures have been taken and what more perhaps could have been considered as the world adapts to the new Covid-19 realities.

Download

Download article14 August 2020

Covid-19, Asia’s lamentable green response, and a slow, slow recovery This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more