High energy prices are another test for the resilience of food producers

Surging energy prices create uncertainty for EU food producers, although national energy support measures reduce the impact and shield production. Nonetheless, food producers need to reassess their energy strategies because mandatory cuts in energy use can't be ruled out this winter and concerns about longer-term gas supply continue to linger

A considerable increase in energy costs for food and beverage manufacturers

Back in 2019 when energy markets were still calm, energy had a 2% share in the total costs of food manufacturers in the EU. Given the sharp increase in energy prices, we estimate that the share currently ranges between 7.5-10% (without price caps or compensation). There are also many signals that some food manufacturers have seen their energy bills rise to up to 30% of their total costs. In food processing, activities such as flour milling, baking and fruit/vegetable/potato processing are relatively energy intensive.

At this stage, there are large differences between what companies are paying for energy because some still have longer-term fixed contracts, while others had to renew their contracts at much higher rates. Companies that locked in energy prices before 2021 and companies that use other energy sources than gas for generating heat are certainly in a more favourable position. However, differences will become less pronounced in the months ahead as older, lower-priced contracts and lucrative hedges expire and government support measures level out some variances.

The Netherlands is an example of how energy costs have become a burden for food producers

- Energy costs as a share of total costs in food and beverage manufacturing

Food manufacturers feel the pinch from second-round effects

Besides the direct impact on costs, there is also a pass-through of higher energy prices towards food and beverage makers as they procure many inputs from agriculture and because they need transportation. Agriculture is generally quite energy intensive (see this previous article), and this is especially the case for horticulture under glass and mushroom growing. Energy represented 25% of total costs in Dutch horticulture in 2021 and, based on energy prices in 2022, that share has gone up to more than 60%. When prices of agricultural products go up due to higher energy costs, the food industry has to deal with this as well. This article looks specifically at energy but it’s good to keep in mind that cost increases for packaging materials, agricultural inputs and labour all add to the cost pressure.

Energy support measures also help to sustain food production

Do we see any signs of a reduction in food production in the EU because of high energy prices? Thus far, food manufacturing output has proven to be quite resilient, aided by the ability to pass on (some of) the higher costs to customers and consumers. This pass-through is illustrated by current double-digit levels for food inflation in the EU (read more in this article). Still, food production data up until August show that production volumes in the food and beverage industry in the EU are higher this year compared to 2021. The long-term trend shows that output volumes are generally not very susceptible to external shocks, apart from a considerable drop at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Currently, we see two mechanisms that help to safeguard EU food production. First, international trade and substitution allow food processors to keep facilities running in case European agricultural supplies fall short. High energy prices haven't led to such a situation yet, but earlier this year trade helped to keep up production of spreads and frozen potatoes amid shortages of Ukrainian sunflower oil. Second, food producers also benefit from government support measures aimed at cushioning the impact of high energy prices on companies and consumers. Examples of recent measures that benefit companies include the reduced VAT rate for electricity and gas in Belgium and the Compensation Energy Costs (TEK) in the Netherlands. Meanwhile, measures aimed at consumers are beneficial because they prevent drastic cuts in expenditure on basic needs such as food.

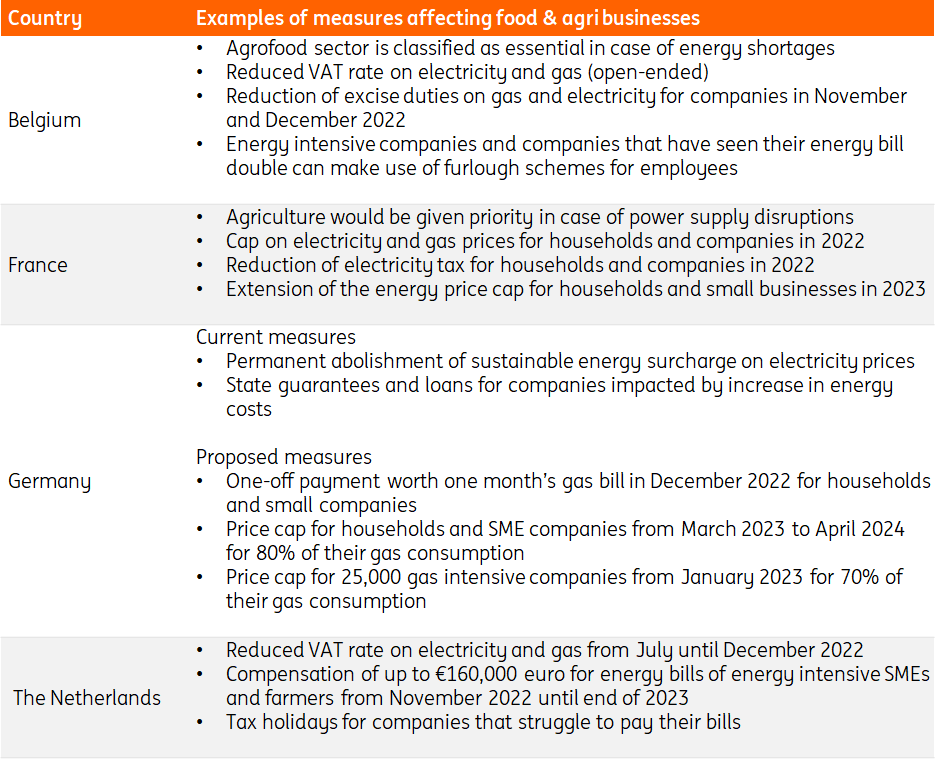

EU countries opt for a range of measures to reduce the burden on companies

Selection of government support measures in several countries

Not all support measures are created equal

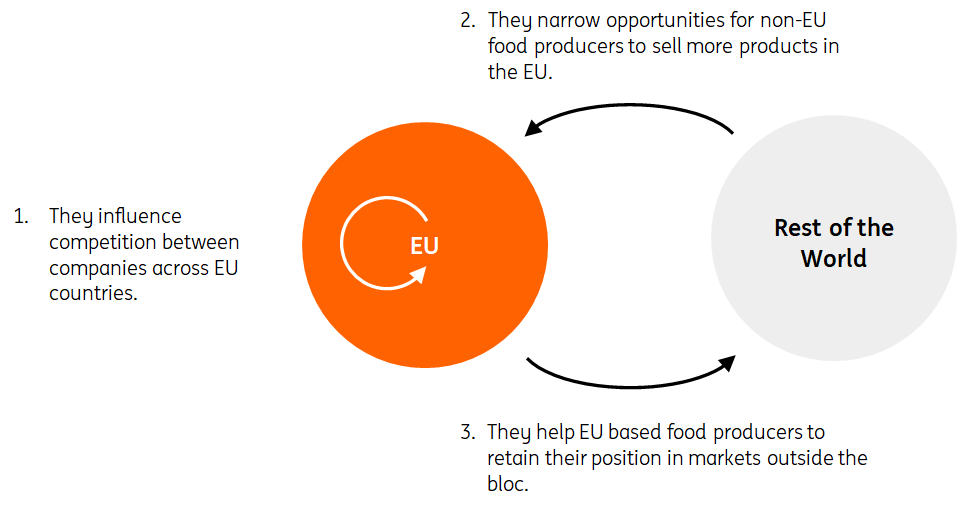

The introduction of all sorts of national energy support measures for companies will temporarily distort competition in multiple ways. This is very relevant as food and beverage is a major export category accounting for almost 270bn euros or 8% of all intra-EU trade. Hence, calls from food industry associations to maintain a level playing field have become louder over the last couple of months. However, differences between countries are likely to grow as some countries have more fiscal room than others. The longer the energy crisis and subsequent support measures last, the greater the chance that they will determine to some extent which companies will weather this storm best.

How support measures distort competition in several ways

Energy costs add additional pressure to EU commodities exports

In our base case scenario, energy prices in Europe will stay at relatively high levels for several years. Assuming energy support measures to be temporary means that the competitiveness of European food products in global markets will deteriorate to some extent. Still, global demand for calories is strong due to population and welfare growth, although affordability is a growing issue. Our expectation is that the general competitiveness of more premium products such as infant formula, beer or frozen fries will be impacted less. But for staple products such as milk powder, olive oil and pig meat, the EU Commission’s Agricultural Outlook has already signalled a decline in 2022 export volumes. This is attributed to a variety of reasons including high energy, feed and fertiliser costs, plus drought and animal diseases. So while higher energy prices are a factor impacting extra EU exports, it’s not the only factor. On the other hand, the strengthening of the dollar is a driver in the opposite direction and is currently supportive of EU exports.

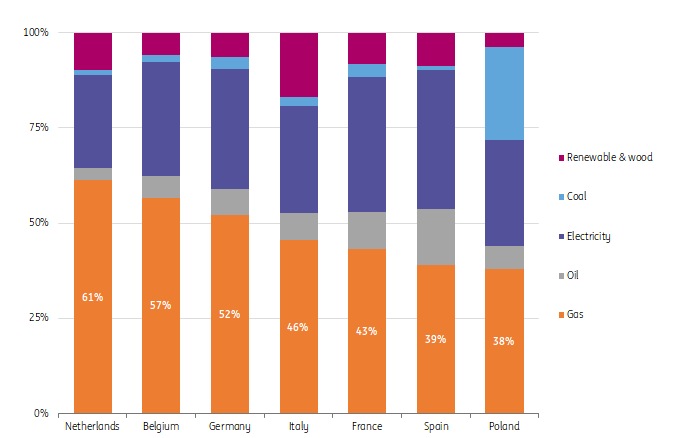

Chance of mandatory gas and electricity rationing poses a major risk

Out of seven major EU food-producing countries, the importance of gas as a source of energy is highest in Benelux (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg) and lowest in Spain and Poland. On top of that, a large part of the electricity supply in the Benelux comes from gas-fired power plants. Although concerns about gas supplies during this winter have eased somewhat, the possibility of gas rationing is a serious downward risk for companies that use gas for generating heat in their production processes, especially if they have limited options for fuel switching. Food processing plants that use other energy sources, such as coal, oil or woodchips, are currently better positioned and often run at full capacity even though their energy inputs are generally less sustainable. Another risk is that EU member states are supposed to reduce electricity demand during peak hours between 1 December 2022 and 31 March 2023. This could force companies to shift more production toward night or weekend shifts or reduce output in case this is not possible.

Food and beverage makers in the Netherlands and Belgium are most dependent on gas

Used energy sources in terajoule in the food, beverage and tobacco industry, 2019

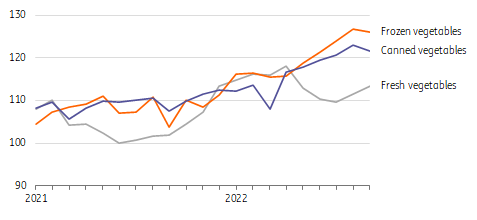

High energy costs will lead to some substitutions on our plate

Elevated energy prices add to food inflation and the current level of food inflation leads to various shifts in food consumption. Such shifts range from an increase in shopping at discounters and higher market shares for private label products to a rebalancing between portion sizes of expensive protein and less expensive carbohydrates in restaurants. The impact of high energy prices might be best visible in the fruit and vegetable section in supermarkets. Here there will be all sorts of substitution effects on display this winter. Due to more energy-intensive processing, conserved and frozen vegetables are becoming less competitive compared to fresh vegetables. On top of that, growing tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers has become a lot less attractive this winter for many horticulture growers in northwestern Europe. If they leave their greenhouses empty, retailers are likely to source more vegetables from growers in Spain, Italy, Morocco and Turkey. These products need less energy to grow, but still require more expensive diesel to transport. In turn that could mean that some consumers will revert to other types of vegetables that provide more value for money.

Prices for processed vegetables have increased more than for fresh vegetables

Dutch consumer price index 2015 = 100, monthly data

The situation creates a need for companies to reassess energy procurement and related investments

Contingency planning is likely to be a major talking point in strategy discussions for 2023 and beyond.

For food manufacturers, reducing their output on short notice is often not easy. This is especially true for companies that have contracted a certain volume of agricultural inputs or for cooperatives that are obliged to purchase milk, animals or crops from members. On top of that, if they reduce output they risk losing contracts and customers which is an even bigger threat to business continuity. While EU farmers are considered to have more flexibility in deciding to reduce production, they generally have high fixed costs meaning that even in unfavourable market conditions they will often decide to ‘plough on’.

Follow-up actions that food manufacturers take to cope with high energy prices:

- Optimise energy use and energy costs: this can be done with additional measures to save energy or by shifting some production to facilities with the lowest energy costs. The latter only works for larger companies with multiple sites that have spare capacity, and only if transport costs allow it.

- Adapt contracts to reduce energy price risks: price escalation clauses can be a way to pass on energy price increases to customers, but often only work when customers are very dependent on a certain supplier or are working with strategic partnerships focused on long-term continuity.

- Fuel switching in production processes to reduce dependency on gas: increase of own energy production. For example, with investments in solar panels or biogas installations.

- Increase electrification efforts: for example, through the installation of electric boilers or heat pumps. In some cases, companies have plans in place but are faced with local capacity constraints on electrical grids.

Why it’s wise to prepare for another difficult winter in 2023/24

This year, the EU has been able to fill gas storage to the current levels partly because there has still been Russian gas available. Futures markets now seem to be concerned about next winter and Europe’s ability to build stocks without the Russian gas supply. In the event of an ongoing supply squeeze, it can be a burden for food manufacturers with many newer or retrofitted food production plants having been catered to run on gas over the past decade. Such concerns provide a clear incentive for food companies to rethink their longer-term energy strategies, including aspects such as contracting energy supply, the optimal energy mix and related investments.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

27 October 2022

Scream if you want to go faster This bundle contains 7 Articles