German housing: Their own fault?

Housing prices in big German cities have been on the rise lately. Is it that supply is just growing too slowly and isn't able to keep up with additional demand – or is there more to it?

All over Europe, consumers are worried about the housing market. In our latest Homes & Mortgages ING International survey, across 13 European countries, 53% of consumers believe their country is on the wrong track when it comes to housing, compared to just 25% who think their country is on the right track.

In terms of housing, Europe's largest economy sets itself apart. In Germany, renting instead of owning dominates the housing market. Rising house prices can take a while to feed through to the renting market, so renters don't immediately feel the impact. But when prices keep rising, those who bought a home profit, while renters just sit and watch as rents catch up.

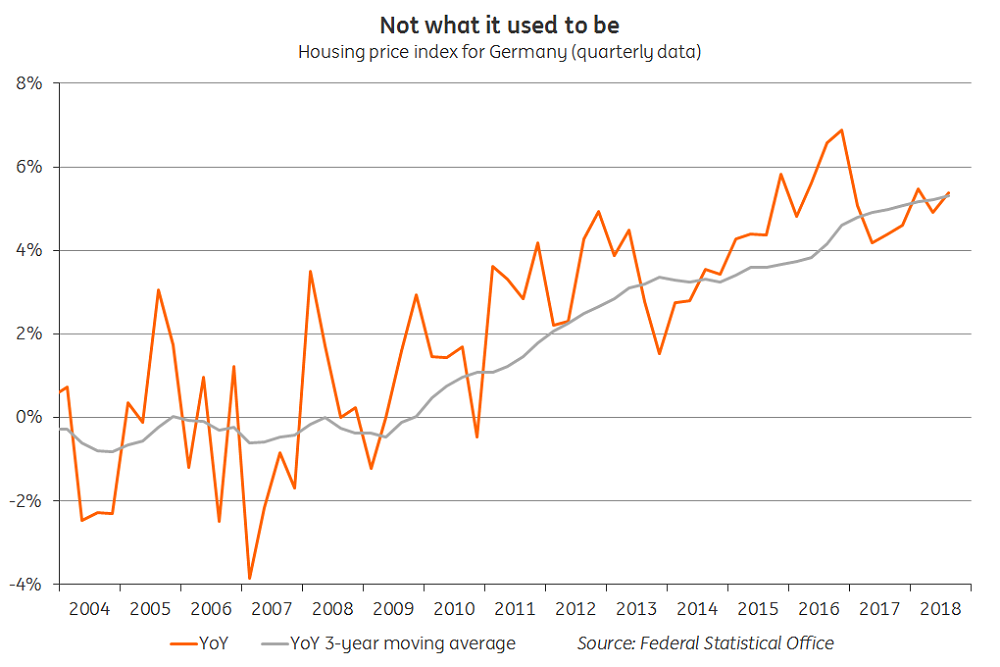

German housing market isn't what it used to be. House price index shows annual growth rates of around 5%, which might not appear dramatic at first but isn't something Germans are used to

In our latest ING international survey on Homes and Mortgages, we found German renters and homeowners look at many aspects of housing similarly. Preferences are usually the same, but might slightly be more pronounced in one group than the other. Renters are less likely to be satisfied with the state of the housing market than homeowners, but even the majority of homeowners think Germany is on the wrong track when it comes to housing. In total, 59% of Germans believe housing in their country isn't on the right track – the third highest number out of 15 countries surveyed and an increase of nine percentage points from 2017.

The German housing market is not what it used to be. The Federal Statistical Office's house price index shows annual growth rates of around 5%, which might not appear dramatic at first but isn't something Germans are used to. For much of the 2000s, the three-year average of this figure had hovered between zero and -1, bearing in mind this is an average that lumps in sparsely populated rural areas with urban hotspots especially the larger cities, such as Berlin, Munich, Hamburg or Cologne, have seen significant leaps in house prices over the last few years that even the Bundesbank finds alarming.

Are people willing to pay to move to the city?

Data from Interhyp, Germany's largest independent mortgage agent, emphasises this too.

Between 2009 and 2017, house prices for the mortgages they arranged have climbed up by almost anything up to 75% in certain larger cities. Land to build on is hard to come by in densely populated areas, which restricts the possible supply of new homes. And property developers have been accused of building expensive luxury apartments instead of affordable flats for more people or foregoing construction work altogether in the hope of cashing in on rising land prices without much hassle. Many Germans are worried their cities might follow in the footsteps of other European metropoles like London or Paris in terms of cost of living.

Germans are worried their cities might follow in the footsteps of other European metropoles like London or Paris in terms of cost of living

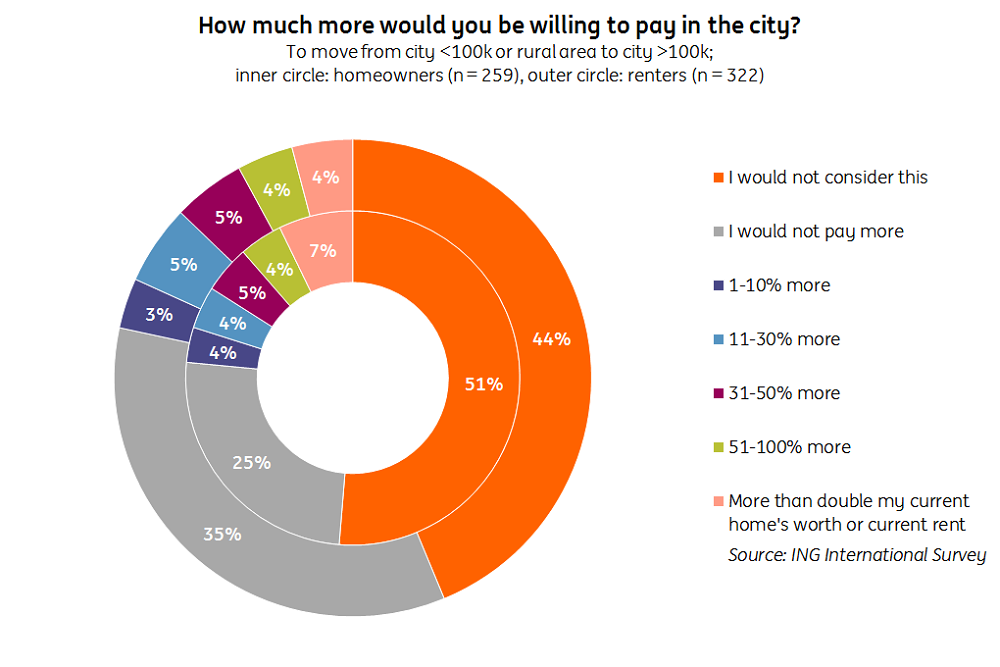

In our survey, we asked German homeowners and renters in rural areas and smaller cities (population under 100,000) if they would be willing to pay more to move to a larger city, i.e. if they would pay more than their current home's worth in a larger city or pay higher rent there than they currently do (assuming everything else about their housing situation would stay the same). Larger cities are perceived to be attractive due to cultural and economic benefits - and we tried to put a price tag on that attraction. Likewise, we asked those already living in larger cities how much lower housing costs would have to be for them to consider a move to a smaller city or rural area.

Saving money in the countryside just isn't an option for many

The attraction that larger cities are perceived to exert on the rural population might be slightly overrated, as our survey finds that more than three quarters of both homeowners and renters in smaller cities and rural areas would either not even consider moving to a larger city and even if they did, wouldn't be willing to pay more than their current home's worth, and the same goes for renters.

Housing isn't just a good like any other - and it seems existing demand lacks price elasticity

Those who would be willing to pay over 30% more only add up to around 15%, which hardly supports the notion that large swathes of the rural population are yearning to become city dwellers and squeeze the urban housing market. But are there other forces at play?

In the traditional view of markets, demand is supposed to react to price changes, which means that with rising prices in the cities, fewer people would want to move there and people would even start to move out of the cities to the suburbs and rural areas to save money. This would keep demand from piling up and prices from rising indefinitely. But if existing demand lacks price elasticity, i.e., doesn't show a significant reaction to changing prices, then a little additional demand can easily spring prices.

Housing isn’t a good like any other

What we find is that more than half of city residents would either never even consider a move to the countryside or would expect the new rent on their suburban home to be at least 50% lower than what they're currently paying. With a threshold of 25%, that number rises to around 80% of city dwellers.

So apparently, people in larger cities are either completely unwilling to move out or would expect a hefty discount as an incentive. They apparently value living in the city so much that demand for housing isn't influenced very much by the money they could save by moving. There is also a first-mover disadvantage: whoever moves out of the city due to the rising prices helps limit further price increases, but obviously won't be around anymore to reap that benefit.

Our survey finds, people in larger cities are either completely unwilling to move out to the suburbs or would expect a hefty discount to incentivise them

So, overwhelming demand from not-yet urbanites would appear not to be the root of the problem. Instead, inelastic demand from current city dwellers seems to be a major cause. This inelasticity might come back to haunt them, as the numbers seem to indicate that among the sub-group which reported to find it difficult or very difficult to pay their rent or mortgage instalment every month, people are even less inclined to move out of the city to save money than the average.

This might seem counterintuitive at first as someone who is already having trouble with housing costs should look for opportunities to save money, one would assume. But then again, it might have been the unwillingness to react to rising prices that got them into trouble in the first place.

This leads us to the truism that housing isn't just a good like any other.

Living in the city (or the countryside, for that matter) doesn't just mean living in some place as opposed to another. People might see it as a part of their identity – that is something no one wants a price tag on.

The German property tax system is currently being redesigned after the Bundesverfassungsgericht (constitutional court) struck down the previous calculation method. This might be an opportunity to incentivise new construction in the cities. Creative policies are needed to deal with the current developments and relying on market forces to settle the issue is unlikely to lead to a widely accepted outcome.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article