Germany: Change would be good

The German economy continues its almost everlasting boom. The next new government should add some minor fiscal stimulus in the coming years, without going for the big economic strike

An impressive growth performance

Germans don’t like change. In this respect, 2017 was an excellent year and 2018 has all the ingredients to be another good one. Growth was and should remain strong; all economic sectors were and should continue to be booming and Angela Merkel was and should remain Chancellor. However, at least a little bit of change is urgently needed.

The economy grew by 2.2% (2.5% when adjusted for working days) in 2017. That's a much stronger performance than expected one year ago.

Germans don't like change. Therefore, 2017 was a good year and 2018 should also be good

Back then, the German recovery already looked rather stretched. Sentiment indicators stagnated and political risks were rising from Brexit and the upcoming Dutch and French elections. Meanwhile, the new US administration was fuelling fears of possible trade wars. One year later, the lesson is clear: “it was not politics, but economics, stupid”. A strong labour market, low-interest rates and low inflation pushed the domestic economy into sixth gear. Also, instead of suffering from protectionism or a Trump trade war, exports surged to new record highs and the long-awaited investment pick-up finally kicked in. The result: the strongest annual growth performance since 2011. Of the last 35 quarters, the economy grew in 32, with an average growth rate of 0.5% QoQ. That's an impressive performance.

That growth performance is even more impressive given that it has been achieved without any significant structural reforms in the last ten years. In this regard, the German economy is actually a good example of how an economy can benefit extensively from earlier reforms, at least if the external circumstances are right.

2018 should bring more of the same

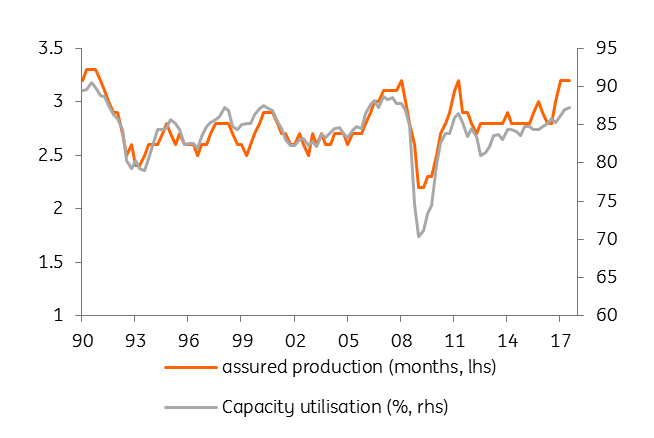

Looking ahead, the same fundamentals which have supported growth in 2016 and 2017 should still be in place in 2018. The only question is how much additional stimulus, low-interest rates, a relatively weak euro, strong domestic momentum and the recent upswing of the entire Eurozone economy can still provide to the mature cycle of the German economy? In our view, quite a lot. Germany still has some upward potential as the output gap is positive but not extraordinary high compared with previous cycles, capacity utilisation is above its historical average but still lower than in 2007 and investments only started to increase last year.

Improving public finances

The strong economic performance has continuously fueled positively into public finances. For the first time since the 1950s, the German government recorded a fiscal surplus in four consecutive years. According to the statistical office, the fiscal surplus came in at 38.4bn euro (1.2% GDP) in 2017, from 0.8% GDP in 2016. While German austerity fetishists will love it, these numbers have been the lubricant for the recent compromise in the coalition talks in Berlin.

The first steps to a new government have been taken

Exactly 110 days after the election, the three parties which have actually governed the country for the past four years agreed to start formal coalition talks. Just to be clear: there is no new German government, yet. But there is a clear determination of the current administration to govern for another four years. The so-called exploratory talks ended with a 28-page-long paper, forming the basis for the coalition talks. According to this compromise paper, which will be the basis for a possible coalition agreement, the next German government will put Europe at the forefront, even though the pro-European stance falls short of clear and concrete measures.

At the same time, the paper remains very vague as to the future of the Eurozone. Phrases such as 'a close partnership with France to reform the Eurozone in order to make it resilient against future global crises' will make Paris happy but keep lots of room for interpretation. The only concrete plan is to transform the European Stability Mechanism into a European Monetary Fund and enshrine it into European law. Some minor changes to the health care system, an increase in child benefits, some minor tax relief and investments in digitalisation and education are in the offing as far as economic policies are concerned.

All of this would currently add up to a total fiscal stimulus of around 45bn euro over the next four years (some 1.2% of GDP).

Is it a breakthrough? Well, it is a breakthrough in the way that it opens the door for Germany to finally get a new government.

No big breakthroughs for the economy

However, it is clearly not a breakthrough for the economy. Judging from the paper, the measures are positive for the economy and there are no real economic blunders or obvious electorate gifts such as, for example, the reduction of the retirement age. As far as economic policies are concerned, the agreement is a continuation of the well-known policies of the last few years: cautious steps forward, rather than any visionary experiments. Pro-growth structural reforms, however, are still hard to find.

The political future depends on the SPD grassroots

The destiny of another grand coalition still dangles on a string, a string in the hands of SPD party members. Dissatisfaction at the party’s grassroots level and fears that the SPD could lose further electorate support in yet another grand coalition make the outcome of the upcoming party votes anything but certain.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

18 January 2018

ING’s Eurozone Quarterly: All systems go This bundle contains 13 Articles