Food companies under pressure to source deforestation-free products under new EU law

The EU's deforestation regulation raises the bar for sustainable sourcing of several commodities and will impact many food companies in some way. Requirements to trace commodities back to their origin can cause practical challenges, push up costs and create a need to find alternate suppliers. Still, any resulting changes in trade flows will be gradual

At a glance: the EU's deforestation regulation

A new EU regulation which aims to ban agricultural products linked to deforestation and forest degradation will come into force this year. This law is another step in the battle against deforestation and comes on top of an increasing number of international agreements and private sector initiatives. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the world has lost 100 million hectares of forest cover over the last decade, which is twice the size of Spain. Net loss was 50 million hectares on a total forested area of four billion hectares. Growing global demand for agricultural products is a major driver for deforestation as it fuels agricultural expansion into (tropical) forests and other ecosystems. More than 50% of deforested land is destined for cropland and almost 40% for pasture.

The regulation obliges companies to ensure that goods that enter or exit the EU market don’t originate from land that has been deforested after 31 December 2020. To comply, they need to be able to trace the commodities and products back to the plot(s) of land where they were produced. Competent authorities in the EU member states will be responsible for the inspection of incoming goods. The level of inspections will be based on a risk classification that determines the obligations of companies and authorities. In the beginning, all exporting countries will be qualified as standard risk. In due time, authorities are supposed to inspect 9% of all shipments from high risk, 3% from standard risk and 1% from low-risk countries.

Regulation is likely to come into force in the second half of 2023

Provisional implementation track

€85bn in agriculture and food trade is in scope

The new EU regulation covers imports of seven commodities including beef and leather, coffee, cocoa, palm oil and soy, plus the trade-in derived products such as chocolate, ground coffee, shoes and tyres. Both imports and exports of these products add up to €85bn in trade. On the import side, it covers about 60% of all of the EU's agricultural imports which total almost €120bn. In the rest of this article, we’ll focus on the five food commodities given that we’re particularly interested in the implications for companies in the food value chain.

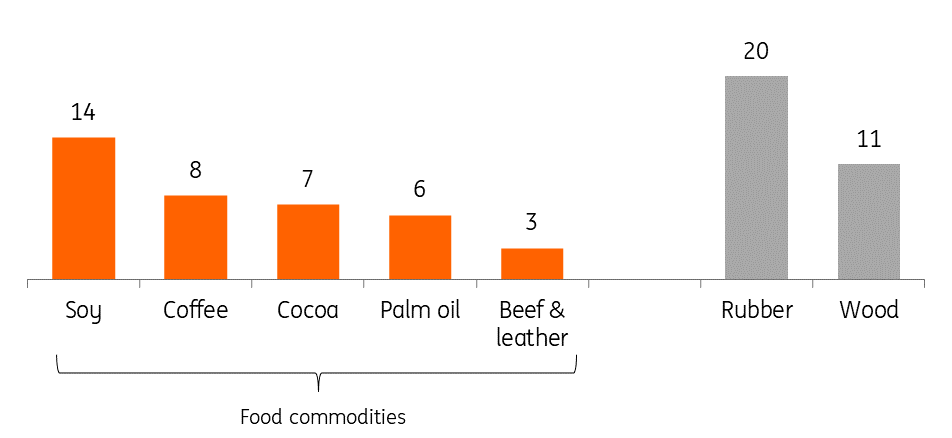

Five food commodities are in scope, with soy the largest based on import value

Value of EU imports, billion euro, 2021

Only a small part carries a recent deforestation risk

One of the major questions is which part of the current trade will be non-compliant under the regulation. To answer that question it’s helpful to distinguish three types of trade flows.

- A large category consists of flows which are already compliant because companies have systems in place to trace commodities back to their origin.

- Probably the largest category is flows which are technically compliant but where companies cannot prove yet that they don’t stem from recently deforested land.

- The smallest group is formed by flows from land that has been deforested after the cut-off date (31 December 2020).

Because of the recent cut-off date, the share of agricultural land in exporting countries that qualifies as ‘recently deforested’ will be quite small in the beginning. For example, we estimate that 1.5-2% of all land used for agricultural production in Brazil and Indonesia can be marked as recently deforested in 2023. This percentage will go up slightly over time as long as deforestation continues. The regulation further increases the likelihood that products from recently deforested lands will be used for domestic consumption or for exports to other countries such as China.

Risks vary between and within countries

Deforestation in large countries such as Brazil and Indonesia often attracts headlines because both countries are major agricultural exporters and have high absolute levels of forest loss. Meanwhile, other countries have much higher relative deforestation rates. As such, the regulation could have a more pronounced impact on European leather imports from Paraguay and coffee imports from Uganda than on soy imports from Brazil or palm oil imports from Indonesia.

It’s good to keep in mind that the rate of deforestation will be one of the criteria used to determine the country's risk classification. Other criteria include the effectiveness of national policies and the participation in international agreements against deforestation. However, deforestation is often very concentrated in so-called ‘deforestation fronts’ within countries (see WWF). So national risk classifications only tell part of the story – even in high-risk countries there will be regions where risks are low or negligible.

Largest net loss of tree cover in Brazil, but Paraguay lost most in relative terms

Countries with highest absolute and relative loss of tree cover between 2000 and 2020

Another trigger for companies to chart their supply chain

Companies across the food and beverage industry will require more information from their suppliers, often large traders, to verify the provenance of products because of the regulation. So traders will need to reach out and identify from which farms they source (in)directly. Meanwhile, European buyers of food commodities will need to draw up specific guidelines in their procurement strategies to be able to exclude deforestation-linked products. Public examples of such frameworks include those companies such as animal feed producer Agrifirm and food manufacturers like Unilever and Upfield.

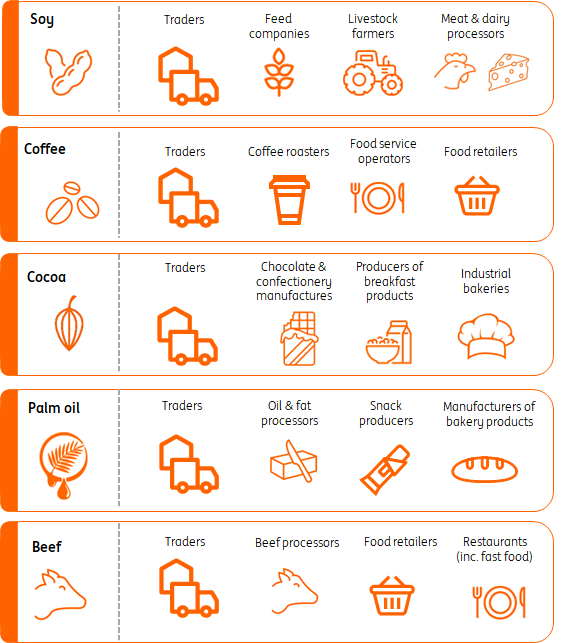

A variety of companies will need to make sure that their inputs are deforestation-free

Examples of types of companies

Many companies won’t have to start from scratch

Many of the traders and food manufacturers involved, particularly the larger ones, won’t have to start from scratch. Often they are already involved in initiatives on sustainable sourcing, like the Roundtable on Responsible Soy and Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. On top of that, there are many public datasets and research articles available, as well as software solutions that help to trace flows (examples include Farm Force and Transparancy One).

As a result, large corporates generally have a good overview of their direct suppliers and first-tier risks. For example, commodities trader Bunge claims to be able to trace all of its soy purchases from direct suppliers back to their origin, and chocolate producer Barry Callebaut claims to know the geographic coordinates of 80% of its direct suppliers of cocoa. But information on indirect suppliers will also be required if companies want to sell that part of their merchandise in the EU. Given that large corporates can easily have tens of thousands of indirect suppliers, it is going to be quite a challenge to ‘know’ every supplier and sometimes it will not be possible to obtain the required information.

Geographic shifts in trade flows; possible but not obvious

We don’t expect major geographical shifts in trade flows towards the EU in the short term. But when retrieving origin information from current suppliers proves too costly, or when deforestation risks are too high, companies will have to adapt their sourcing. Below we have summed up what could happen in that case.

Improving traceability is easier to do in supply chains where traders work with large and direct suppliers and get more difficult when there are lots of smaller indirect suppliers. As such, the regulation is an incentive for companies to have more direct suppliers in their EU supply chains, but it can also be detrimental for farmers that are indirect suppliers. Either way, there will still be buyers in the market for commodities that EU buyers steer clear from unless similar regulation becomes the norm in other countries instead of the exception.

Shifts in sourcing, what might happen?

Possible outcomes of the regulation for trade in the five commodities

Compliance obligations and less suitable supply pushes up costs

It is fair to assume that the costs for sourcing deforestation-free commodities will be higher than without the regulation because of the following reasons:

- There will be both one-off and recurring costs for companies to assess risks and monitor supplies. The European Commission estimates that the one-off costs for companies to set up due diligence would range from between €5,000 and €90,000. Recurring costs will largely depend on the complexity of the supply chain.

- On top of that, the regulation will have an upward effect on the prices of commodities destined for the EU because less supply is able to meet EU criteria in the new situation. When companies need to switch suppliers, it will take time to develop alternative supply chains and sourcing elsewhere is usually more expensive or less compatible with required quantities and quality standards.

Different approaches to sustainable sourcing

Keeping deforestation-free products segregated from other products at each step in the supply chain is not a common practice in the food commodities trade as it greatly increases costs. However, it is common practice in organic supply chains. Companies that currently source more sustainable inputs often buy certificates that guarantee that a certain volume in the market has been produced according to a certain standard (similar to when you buy green electricity). But this model (‘Mass balance’) doesn’t enable physical commodities to be linked to the exact location where they have been produced. Other sourcing methods such as ‘Origin matching’ and ‘Area Mass Balance’ offer a compromise. Ultimately it will depend on the implementation of the regulation which model will become the default option.

Supportive for some food companies, detrimental for others

The regulation changes the operating environment for companies. It is supportive for businesses that have already taken steps to prevent deforestation because their competitors now also have to do more. It is also supportive for EU farmers that produce alternatives for the commodities in scope, such as farmers that grow crops like soy and rapeseed and (grass-fed) cattle farmers. But the regulation is generally detrimental to the competitiveness of pig and poultry farmers as it likely pushes up their feed costs. Meanwhile, European exporters of coffee and cocoa products could face increased competition from processing plants elsewhere, which can put some pressure on their exports to non-EU markets. In general, it can also weaken the position of the EU as a trading hub for food commodities as some flows might go straight from producer countries to end markets without making a stop in the EU.

All in all, one of the major aims of this regulation is to make sure that negative external effects of food production such as carbon emissions and biodiversity loss are better reflected in the price of food. Such steps are inevitable in the context of the ongoing climate crisis. In the years ahead, food companies shouldn’t be surprised to see more policies in this field as countries step up their efforts to curb climate change.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article