Exploring the depth of Asia’s unconventional central bank easing

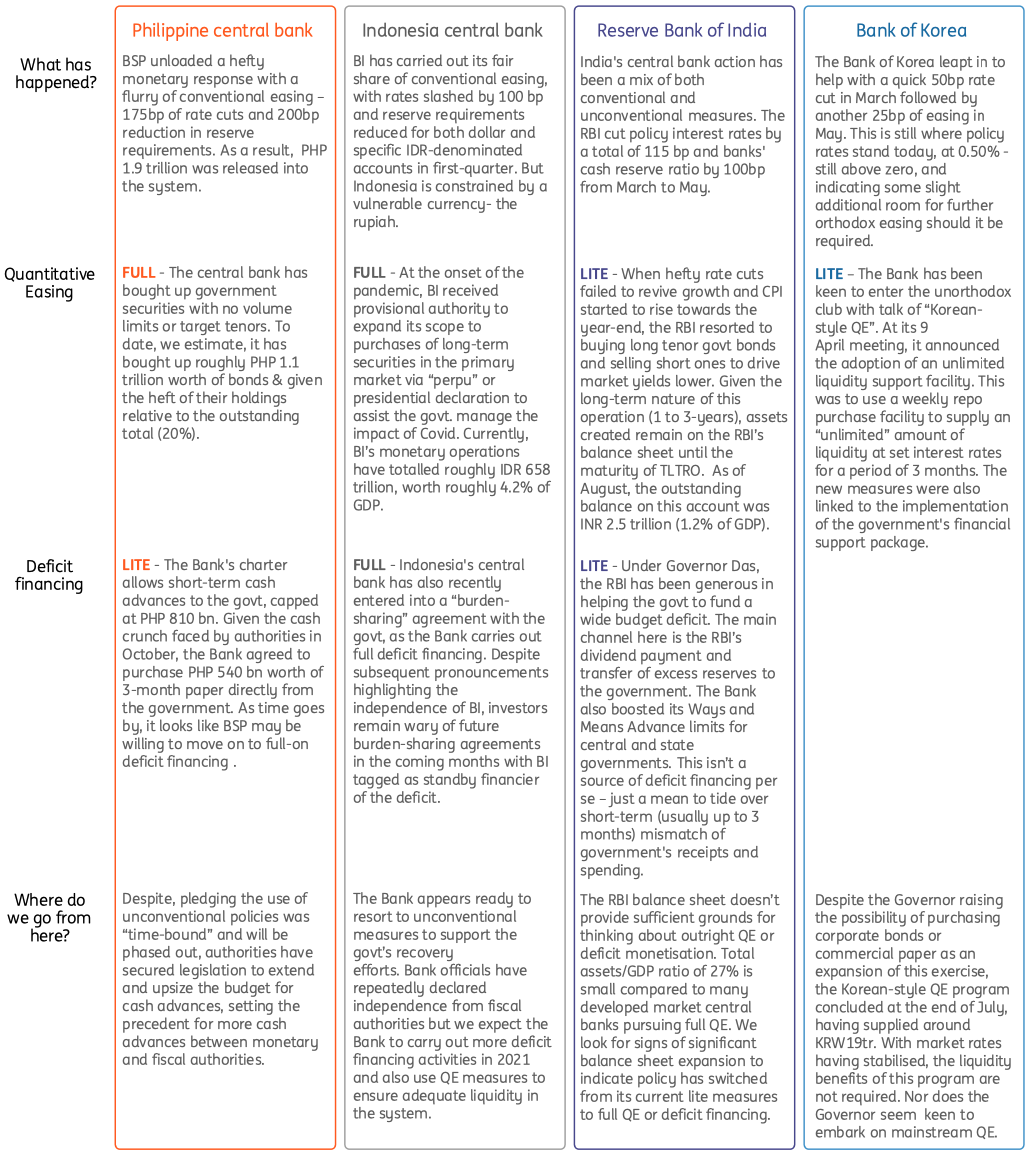

“Unorthodox” monetary policy is becoming so mainstream now, that what was once considered the edgy domain of some developed markets, is now even being dabbled in by some emerging market central banks including the Philippines, Indonesia, India and Korea with some trying to get away with “lite” versions of both QE and even direct monetary financing

Asia Pacific – unorthodox policy by country

Once impassable, now prevalent

Across the world, the Covid-19 pandemic has turned life on its head. Things once considered impossible (majority home working) have proved eminently achievable. Fiscal policymakers have also ripped up the rule books – better to risk a rating downgrade than to let the economy implode – and deficits are ballooning. Again, seemingly without major ramifications.

Monetary policies are beginning to push in directions that less than a year ago would have seemed absolutely unthinkable including in the Asia Pacific region

And on the monetary policy side too, there are changes. Zero real interest rates were once seen as an impassable line in the sand for most emerging market economies. But this, or even negative real rates are now the norm for many. And for others, policy rates are now also nearing the absolute zero lower bound.

Even this doesn’t seem enough for some, and at the margin, policies are beginning to push in directions that less than a year ago would have seemed absolutely unthinkable including in the Asia Pacific region. Some central bank actions are beginning to look a bit like quantitative easing (see also this broader EM note from June), and even in some cases, direct monetary financing.

Markets seem to be paying little attention as previous norms are broken, but as normality resumes, their tolerance for such policies may lessen or even reverse.

Asia: Central bank policy rate and inflation rate (%)

Unorthodox policies – a primer

Given the limitations of rate policy in achieving desirable economic outcomes in terms of either economic growth, full employment or low positive inflation targets, a number of developed market central banks in recent years have tried to squeeze a little more juice from the dried up husks of their policy arrays.

Such policies have typically involved some form of balance sheet expansion, with quantitative easing the main policy of choice. In very simple terms, quantitative easing was an active expansion of the central banks’ balance sheet, using created money balances (central banks directly control the supply of “cash” money) which were exchanged in the secondary market for financial assets – usually longer-term national government bonds.

As time has passed, issues of asset credit quality have been superseded by the needs of market liquidity, and such purchases have expanded to include mortgage-backed securities, corporate paper, exchange-traded funds, and municipal/local government securities and others.

In the end, it turns out that QE has been pretty ineffective at even enabling modest inflation targets to be met. Any inflationary impact of QE is largely confined to financial asset markets.

The aspect of QE that made it a novel policy tool, was the fact that the purchases were done with created money. This was “money printing” in terms of old school attitudes, and had previously been avoided, other than what was necessary to keep pace with the nominal growth of the economy and to prevent money velocity bottlenecks. A little “seignorage” has always been regarded as acceptable, but anything beyond this was viewed as recklessly inflationary policy.

In the end, it turns out that QE has been pretty ineffective at even enabling modest inflation targets to be met, with any inflationary impact being largely confined to financial asset markets, and with only very limited real macroeconomic effects. And perhaps for that reason, central banks have become emboldened to push their policies further and further, tweaking them into new variants such as the recent demand for yield curve control.

Central bank balance sheet expansion via Quantitative easing

How does it work?

Nonetheless, at its heart, the policy simply creates cash on the liability side of the central banks’ ledgers and then exchanges it for assets held by others, boosting the cash balances of those from whom they purchase assets, and in turn the asset side of their own balance sheets. The reduced availability of “low risk” financial assets outside the central bank - the portfolio balance effect – pushes up their price, and by extension, encourages the purchase of riskier assets, equities, high yield credit etc, supporting these markets too.

Not all developed market central banks were initially ready to take the plunge and undertake quantitative easing. For years, the European central bank limited itself to a form of QE-lite, expanding their balance sheet, but only temporarily through long-term refinancing operations (LTROs), which were time-limited. This essentially created a limit to the duration of the stimulus and built-in its reversal, perhaps lessening its impact.

Such LTRO and targeted (T)LTRO approaches could be viewed more as a counter to poor market liquidity than an overt attempt at domestic demand management, which full quantitative easing, it could be argued, tries to be.

QE vs. Deficit financing

And, direct deficit financing

In reality, full QE also has only a finite impact on the central bank balance sheet, except for perpetuals, eventually, outright purchases of fixed income assets mature, and cash will return to the central bank. To overcome this shortcoming, proceeds of maturing assets have often been re-invested, maintaining the balance sheet expansion until such time as it was viewed it was no longer needed, and hence providing an even stronger signal of expansionary intent to market participants.

So far, no developed central bank has embarked on direct monetary deficit financing, though give it time… This is an even more overt form of money printing and simply pays for government borrowing directly in primary markets with printed money. At this point, the central bank abandons any pretence of independence and simply becomes a tool of the government, printing cash to pay for the government’s deficit spending. Monetary policy becomes indistinguishable from fiscal policy.

Currently, this feels like a step too far even for most developed market central banks. But with their fiscal options more limited, even in these unusual times, some emerging market central banks seem to be trying to make up for their limited fiscal leeway by leaning in the direction of such direct monetary financing, in particular, via temporary “advances” to government.

Some emerging market central banks seem to be trying to make up for their more limited fiscal leeway by leaning in the direction of direct deficit financing in particular, via temporary “advances” to government

What looks like a temporary advance today, may end up lingering long past any reasonable concept of short-term cash flow management which is how these measures are currently described. And although such direct financing doesn’t directly lower gross government deficits or their debt pile relative to GDP, it does internalise it, by turning the central bank into the monetary arm of the government, and in turn, lowering the net deficit / net debt to GDP ratios.

In the current market climate, where almost anything seems possible, central banks in Asia seem to be getting away with at least “lite” versions of both QE, and in some cases, direct monetary deficit financing.

Asia Pacific – unorthodox policy by country

We now take a closer look at this and consider whether these policies remain acceptably “lite” or have crossed the threshold posing a risk should we ever return to a situation where markets become more choosy about where they place their funds.

Philippine central bank: Getting rather busy

The Philippine central bank delivered a hefty monetary response to the pandemic, deploying a flurry of conventional easing - 175 basis points of rate cuts and 200 bps reduction in reserve requirements) and has since ventured into unconventional policies.

As a result of its easing measures, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas’ released roughly 1.9 trillion Philippine pesos into the system to calm financial markets with the central bank carrying out both direct deficit financing and quantitative easing.

BSP - Quantitative easing (Full)

The Philippine central bank has engaged in quantitative easing measures, buying up government securities from the secondary market with no volume limits or target tenors. To date, we estimate that BSP has bought up roughly PHP 1.1 trillion (5.6% of GDP) worth of bonds from the market and given the heft of their holdings relative to the outstanding total (20%).

We believe BSP will likely hold on to these bonds until maturity for fear of rattling financial markets.

BSP balance sheet

BSP - Deficit financing (Lite)

Early on in the pandemic, the central bank initially agreed to a government cash advance via a PHP 300 bn six-month repurchase agreement in March, which has since been settled. The Bank's charter allows it to conduct short-term cash advances to the national government, capped at PHP 540 bn or 2.7% of GDP. Given the cash crunch faced by fiscal authorities in October, the Bank agreed to purchase PHP 540 bn worth of three-month paper directly from the national government with central bank Governor Benjamin Diokno indicating he remained open to additional support in the future.

BSP may be willing to move on to full-on deficit financing.

Meanwhile, recent legislation has granted authority for the central bank to upsize cash advances to the government to PHP 810 bn or 4.1% of GDP while also extending the repurchase agreements for up to two years. As time goes by, it looks like BSP may be willing to move on to full-on deficit financing with finance minister Dominguez indicating that BSP will likely be called upon to do more in terms of debt financing in 2021.

BSP - Where do we go from here?

BSP Governor Diokno has pledged that the use of unconventional policies was “time-bound” and that measures would gradually be phased out once economic conditions improve. Despite these pronouncements, we note that the authorities have handily secured legislation to extend and even upsize the budget for cash advances, setting the precedent for additional cash advances between monetary and fiscal authorities in the future.

With the economy in deep recession, BSP has chosen to go almost all-in with full-fledged quantitative easing measures alongside lite-deficit financing agreements.

Indonesia's central bank: Going all in

Indonesia's central bank has carried out its fair share of conventional monetary easing, cutting policy rates by a total of 100 bps while also reducing reserve requirements for both dollar and specific IDR-denominated accounts in 1Q. Growth momentum has understandably fallen sharply with Indonesia recording one of the highest Covid-19 rates of infection in the region with 2Q GDP falling into contraction.

Indonesia's central bank appears to be constrained by a vulnerable currency

Despite the need to help bolster GDP via additional policy easing, the central bank appears to be constrained by a vulnerable currency with Indonesia rupiah down 5.5% for the year, weighed down by substantial foreign selling in the local bond market in 1Q. Being constrained from easing monetary policy via conventional measures, BI has not shied away from enacting unconventional measures to help bolster the economic recovery from the pandemic.

BI - Quantitative easing (Full)

Prior to the pandemic, the central bank had been conducting repurchase agreements to help manage liquidity conditions since 2008 with the central bank limited to taking on short-term securities from the secondary market.

At the onset of the pandemic, BI received provisional authority to expand its scope to purchases of long-term securities in the primary market via “perpu” or presidential declaration “in order to assist the Government manage the impact of Covid-19 ”. BI was granted authority to purchase long-term primary market securities only as a “last resort” should the market be unable to absorb debt sales by the government to cap upward pressure on yields given heightened uncertainty. The perpu also granted the central bank the authority to purchase longer-dated securities in the secondary market also to help preserve financial market stability and to ensure adequate liquidity in the financial system.

Currently, BI’s monetary operations have totalled roughly IDR 658 trillion, worth roughly 4.2% of GDP.

Indonesia's central bank monetary operations

BI - Deficit financing (Full)

Indonesia's central bank has also recently entered into a “burden-sharing” agreement with the national government, as the central bank goes head-long into deficit financing.

Market anxiety spiked as soon as reports on the rumoured deal circulated with concerns about central bank independence weighing on sentiment. BI finalised the IDR 575 trillion (3.6% of GDP) agreement with fiscal authorities in early July with the central bank agreeing to buy up IDR 397.5 trillion at the policy rate to fund Covid-19 relief efforts.

The Bank also agreed to act as the standby buyer for primary market debt worth IDR177 trillion with the central bank shouldering the cost which is pegged at BI 3-month repo rates less 1 percentage point with the proceeds used to recapitalise distressed small and medium-sized enterprises. For the private placement worth IDR 397.5 trillion, BI would return the bond yield to the government in full.

Investors had initially absorbed the “burden-sharing” agreement after authorities justified such manoeuvres as necessary given the crisis while vowing that the agreement was a “one-off” deal. In August, jitters re-emerged during the passage of the 2021 national budget with fiscal authorities citing BI as standby financier for the deficit all the way through to 2022. Despite subsequent pronouncements (even from President Jokowi) highlighting the independence of BI, investors remain wary of future burden-sharing agreements in the coming months with BI tagged as standby financier of the deficit.

BI - Where do we go from here?

With the economy in recession, Indonesia's central bank appears ready and willing to resort to additional unconventional measures to support the government’s recovery efforts.

Bank officials have repeatedly declared independence from fiscal authorities but we do expect the central bank to carry out additional deficit financing activities in 2021 while also employing quantitative easing measures to ensure adequate liquidity in the financial system.

Reserve Bank of India: Nowhere near full QE

Prevailing fiscal policy constraints in helping the economy turn the Covid-19 tide saw the Reserve Bank of India taking the lead in providing stimulus during this pandemic. Indeed, a significant portion of the 10.5% of GDP “total stimulus package” announced by the government on May 2020 comprised monetary measures.

RBI's unconventional policy falls on the lite side of both quantitative easing and deficit financing, though it’s more of the former than latter.

Like many other Asian central banks, India's central bank action has been a mix of both conventional and unconventional measures. The RBI cut policy interest rates by a total of 115 basis points and banks' cash reserve ratio by 100bp from March to May. This came on top of the 135bp of rate cuts in 2019, more than most Asian central bank eased in 2020. The more unconventional measures have taken the form of liquidity support via LTRO, TLTRO, variable repo operations, enhanced marginal standing facilities, financing window for non-bank finance companies, and increases in the “Ways and Means Advances” to the government.

We think RBI unconventional policy falls on the lite side of both QE and deficit financing, though it’s more of the former than latter.

RBI - Quantitative easing (Lite )

Unconventional policy came into play well before the pandemic hit. The economy was already on a downward path in 2019. As hefty policy rate cuts of last year failed to revive growth and inflation started to accelerate towards the year-end, the RBI resorted to ‘Operation Twist’ – buying long tenor government bonds and selling short ones to drive market yields lower, a form of yield curve control that the US Fed pioneered in the 1960s and re-used following the global financial crisis. The move helped to curb upward pressure on longer-term yields, making it one of the preferred policies this year – the RBI has had four rounds of this Operation since April, swapping a total of INR 100 billion or 0.05% of FY19-20 GDP from short-term to long-term bonds each time, without any net impact on its balance sheet.

In its first policy meeting of 2020 held in February, the RBI injected about INR 1 trillion (0.5% of GDP) of liquidity through 1 to 3-years repo operations (LTROs) and also eased bad loan norms for small borrowers and reserve requirements for select lending. As the nation-wide lockdown forced the economy to a grinding halt by late March, the RBI delivered 75bp of repo and 90bp of reverse repo rate cuts and also lowered the cash reserve ratio by 100bp. That was not all. It launched INR 1 trillion of TLTRO for tenors from 1 to 3-years at a floating rate linked to the policy repo rate (4.40% at the time) and INR 1 trillion of variable repo operations. In mid-April came another TLTRO 2.0 for INR 500 billion and a financing window for NBFCs for INR 500 billion.

While the RBI continued to pile up liquidity support via unconventional measures, including another INR 1 trillion of on-tap TLTRO announced in the latest policy meeting earlier this month, the market response to the TLTRO operations has been rather tepid. So is their balance sheet impact. Given the long-term nature of this operation (1 to 3-years), the assets created remain on the RBI’s balance sheet (classified as loans and advances to banks) until the maturity of TLTRO. As of August, the outstanding balance on this account was INR 2.5 trillion (1.2% of GDP).

Lower policy rate failed to stimulate lending

RBI - Deficit financing (Lite)

As the RBI embarked on an aggressive easing and the government launched a record INR 12 trillion borrowing programme for the year, noise grew about outright QE or even buying government bonds directly from the primary market. While former RBI policymakers warned against such policies on the grounds of their potentially inflationary consequences, Governor Shaktikanta Das hasn’t shown any particular inclination towards them either.

However, under Governor Das, the RBI has been generous in helping the government to fund a wide budget deficit. The main channel here is the RBI’s dividend payment and transfer of excess reserves to the government. The government’s increased demand on the RBI for these funds was a controversial topic just recently, raising questions about the central bank’s independence under the current regime. Indeed, this payment jumped to a record INR 1.76 trillion in FY2018-19 (July-June, the RBI’s accounting year), 64% higher than what the government had budgeted for the year and over a three-fold increase from the INR 500 billion paid in the previous year. The transfer for FY2019-20 has slowed sharply though to INR 571 billion, and it is projected to be around that level too in the current year.

The central bank also boosted its Ways and Means Advance limits for central and state governments. This isn’t a source of deficit financing per se – just a mean to tide over short-term (usually up to three months) mismatch of government's receipts and spending. The RBI lifted its WMA limit to INR 2 trillion for the first half of current financial year and to INR 1.25 trillion for the second half from INR 75 billion and INR 35 billion corresponding periods of the last year. Being for short-term use, WMA’s are generally underutilised and aren’t a source of RBI balance sheet expansion.

Both the dividend transfer and WMAs may be viewed as creeping monetisation of the deficit, as the RBI’s former deputy governor, Viral Acharya, pointed out recently. He also questioned the RBI’s independence under the current regime before he quit in early 2019.

RBI - Where do we go from here?

The RBI balance sheet doesn’t provide sufficient grounds for thinking about outright QE or deficit monetisation.

The balance sheet expanded by 30% over the last financial year ended in June 2020. While this may align with the aggressive monetary expansion over this period, the expansion is mainly explained by the revaluation of gold and reserves, foreign investment, and loans and advances on the assets side, and currency and deposits on the liabilities side. A surge in demand for cash during the Covid-19 lockdown underlines increased currency circulation. As excess liquidity from monetary expansion countered by weak demand, funds flew back to the RBI as deposits via reverse repos. About a 50% jump in the foreign investment assets reflects the reinvestment of swelling FX reserves. Lastly, a 42% rise in domestic investment and loans and advances results from huge liquidity operations.

Moreover, the total assets/GDP ratio of 27% is very small compared to many developed market central banks pursuing full QE. We would look for signs of significant balance sheet expansion from here as indicating that policy has switched from its current lite measures to full QE or deficit financing. The RBI seems to be a long way from that at present. And with stagflation risk is lingering on horizon, we don’t believe this is likely either. Indeed, monetary policy has probably reached about as far as it can go, and more of the same is our baseline view until the economy recovers the entire loss of output caused by Covid-19.

Bank of Korea : Temporarily dabbles with QE-Lite

As one of the more developed markets in the Asia Pacific region, it is arguable that adoption of unorthodox monetary policies by the Bank of Korea would represent a smaller departure from normality than it would for some of the less developed markets considered earlier.

Yet despite this, the Bank of Korea’s journey into these uncharted zones has been timid, and “talked up” rather than delivering any genuine move into unorthodox policy. Such moves have also been very short-lived, with policy currently looking distinctly orthodox.

Bank of Korea - Quantitative Easing (Lite)

The Bank of Korea was a reluctant easer during 2019, beginning to cut its 7-day reverse repo rate target from 1.75% in July, reversing some of the tightening that it had resumed towards the end of 2018. The July 25bp rate cut was followed by a further 25bp of easing in October, taking the policy rate to 1.25%, which was where most analysts anticipated the rate cycle would end.

Covid-19 spurred the Korean government into action early in 2020, with Korea one of the first countries in Asia to record substantial numbers of cases after the outbreak in China. The BoK leapt in to help with a quick 50bp rate cut in March and followed up with a further 25bp of easing in May.

Korea's central bank has been keen to claim entry to the unorthodox club with talk of Korean-style QE.

This is still where policy rates stand today, at 0.50% - still above zero, and indicating some slight additional room for further orthodox easing should it be required. But despite apparently having more room for additional orthodox policy, the central bank has been keen to claim entry to the unorthodox club with talk of “Korean-style QE”.

This Korean-style QE has taken the following form. At its April 9 meeting, the Bank announced the adoption of an unlimited liquidity support facility. This was to use a weekly repo purchase facility to supply an “unlimited” amount of liquidity at set interest rates for a period of three months. The new measures were also linked to the implementation of the government's financial support package.

To make this work, the BoK expanded the range of institutions that could take part in these liquidity exercises, and also broadened the range of eligible securities.

Describing their measures at the time as “Korean-style” QE, the policy does look to have allayed concerns about market liquidity, which had seen 10-year government bond yields spiking higher during March. But importantly, the measures were temporary, limited to three-month repos, and rather than balance sheet expansion through money printing, look like little more than liquidity management. The fact that they were “unlimited” hints that there may have been some willingness to print to ensure sufficient liquidity was extended. But this would, in any case, have been a temporary phenomenon, and seems a very long way from QE as we understand it.

Monetary base and Bank of Korea liabilities to financial institutions

Bank of Korea - Where do we go from here?

Despite Bank of Korea Governor Lee Ju-Yeol raising the possibility of purchasing corporate bonds or commercial paper as an expansion of this exercise, the Korean-style QE program concluded at the end of July, having supplied around KRW19tr. Though it has been kept on ice and could be resumed if needed.

With market rates having stabilised, the liquidity benefits of this program are not currently needed. Nor does it appear that Governor Lee is keen to embark on more mainstream QE directions, describing these in a recent speech as “premature”. All told, this experience seems like a departure from the BoK’s usually conservative approach to policy, and one that it did not feel entirely comfortable with. We doubt that they will return to similar measures any time soon.

Why markets don't seem in a hurry to penalise

Across the Asia Pacific region, as the Covid-19 pandemic has raged, the stresses and strains on governments' abilities to fight the economic damage caused by the virus with traditional monetary and fiscal policy has been strained. And this strain has been more evident for emerging market governments, always keeping one eye on the rating agencies and market support, than it has for the richer, more developed economies.

We see more evidence for a creeping support for government fiscal policies from central banks in the Asia Pacific region.

It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that we see more evidence for creeping support for government fiscal policies from central banks in the less developed markets of the Asia Pacific region than we do from the richer, more developed economies. With the exception of some big talk from Korea, the action has been largely at the other end of the spectrum, India, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Recovery in these latter economies is likely to remain slow, and pressure on governments fiscal balances to remain substantial. So we don't rule out a further creep over time in the direction of both full QE, as well as towards more direct monetary support measures for fiscal policy. And at some point in the future, maybe when markets are no longer being accommodated to such a large extent globally as is currently the case, this could prove very troubling to these markets.

For now, however, so long as these countries can use such policies to keep economic growth from outright collapse, markets seem to be in no hurry to penalise them.

Download

Download article30 October 2020

From the ECB to yours: the outlook for banks This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more