Europe’s booming labour market needs to brace for change

The luxury of labour hoarding is coming to an end in the eurozone as corporate profits dwindle. And that’s going to mean wage growth will ease, unemployment will tick up and we’ll see more bankruptcies too. A terrible prediction? We’re actually just getting back to normality

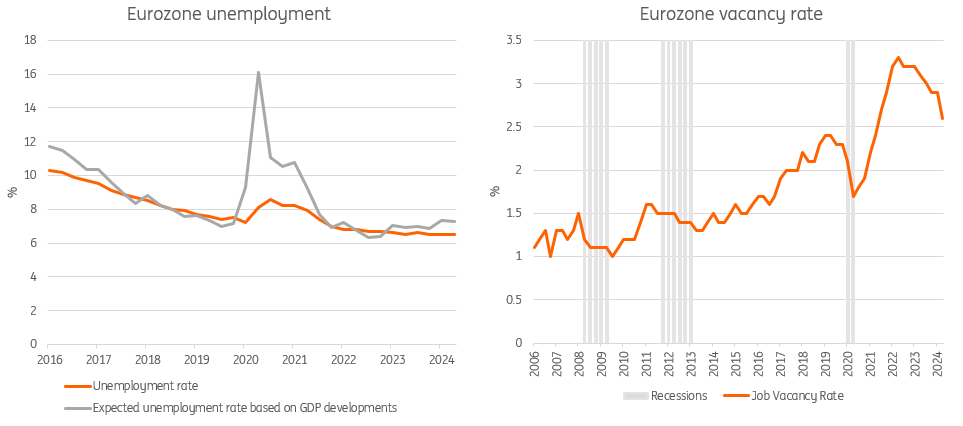

The eurozone economy has been struggling since late 2022, but its labour market has continually been overheating. It's been something of a conundrum that the unemployment rate is at historic lows of 6.4%, given the economy's hardly grown for two years. In 'ordinary' times, that labour pressure would never have been so intense. But we are now getting back to some sort of normality. The days of stagnation without rising unemployment are set to come to an end.

Look at vacancy rates. They've been coming down from historical highs, but they're still above pre-pandemic levels. Coming down, too, is the number of businesses reporting that labour shortages are limiting their growth. Those two things normally coincide with recession. But, despite the weak economic data we're getting month after month, that's not where the eurozone is right now.

So, we're arguing that we're starting to transition into something far more normal, and it will have a more noticeable effect next year, with unemployment creeping up and wage growth trending markedly lower. Here's why...

Okun’s law suggests a higher unemployment rate, but vacancies are dropping

An extraordinary buildup of labour pressures

The labour market has seen two clear breaks after the initial pandemic shock in 2020: a drop in hours worked and a decrease in productivity. Average hours worked by Europeans dropped markedly due to short-time work schemes and lockdowns, and they've never fully recovered. Similarly, the productivity of Europeans per hour worked has also not been able to match the pre-pandemic trend of already lacklustre labour productivity growth.

The combination of those two breaks has resulted in extra demand for workers to match the gap of fewer hours worked per person and less output produced per hour worked. Assuming total economic output remains constant over time (despite the limitations of this assumption) and that labour productivity and average hours worked continue their pre-pandemic trends, there would be a need for 4.3 million fewer workers than are currently employed.

Productivity and work hours have seen a trend break since the pandemic, favouring extra workers

While the reasons for the slow productivity and average hours worked are not clear-cut, it does look like this has happened in a time of significant labour hoarding. Businesses afraid of losing good workers have held on to them at lower output or lower hours worked to make sure that they don’t have to replace them in a labour market that is so overheated. In the US, there was anecdotal evidence about retention bonuses being given to keep people on board. For Europe, you could argue that fewer hours and lower output are like a retention bonus-in-kind at the moment.

Besides that, the public sector has increased expenditure significantly since the pandemic, which has resulted in rapid growth of employment in the (semi-) public sector. Employment in the sector is now about 7% larger than before the pandemic, while private employment is just 3% above the level of the fourth quarter of 2019. This adds to the labour shortages experienced in the private sector, and given that the (semi-) public sector, on average, works fewer hours and has lower productivity, it seems to have contributed to the breaks in trend mentioned before through a compositional effect.

(Semi-) public employment has far outpaced private employment growth since late 2019

Strong profit growth has been key to recent labour market developments

The extraordinary increase in labour shortages has happened at a time when profit growth soared thanks to the high inflation environment. This has allowed businesses to absorb the extra costs of hoarded labour in their margins as margin growth was very strong anyway. In that light, labour hoarding looks like a sign of luxury that companies could “afford” due to the inflation shock.

With inflation normalising and the economy slowing, profit growth has again come under pressure. At this point, growth in companies’ gross operating surpluses has fallen from over 10% in early 2023 to less than 1% now. This has already coincided with a lower vacancy rate in the same period, but employment has remained high. Worries about labour availability, also related to ongoing and accelerating demographic change, remain, but with profit growth close to zero, the affordability of labour hoarding looks very different to that in 2022 or 2023.

Profit growth has faltered as inflation normalised making further wage bill increases much more painful

What's going to give?

Even though profit growth has dropped to levels close to zero, wage demands continue to come in high. When looking at different countries, Germany and the Netherlands still stand out with high wage demands, while others seem to moderate more quickly. From a union perspective, this difference is understandable as the Netherlands and Germany have not yet seen their real wage growth catch up with pre-inflation shock levels.

Still, with profit growth already falling quickly and a series of negative headlines from industrial companies, particularly in Germany, the question is what is going to give. Will corporates take this in their margins? Will they lay off workers? Or will they negotiate wage growth down?

Real wage growth is still returning to pre-inflation shock levels

Our expectation? All of the above. Unions will likely start to worry more about possible unemployment now that real wage growth is approaching or has exceeded levels seen before the inflation shock. The rise of China as an industrial competitor and the broader debate about Europe’s weakening competitiveness will also enter the equation of both unions and employers. As a result, wage growth should clearly slow down over the course of next year. The alternative is an increase in redundancies and bankruptcies, although we don’t expect this to be dramatic.

At the same time, governments are starting to tighten their belts. While this is happening at different speeds and with differing effects on employment, we do think that the pace of employment growth in the (semi-) public sector will be under pressure because of it.

All of this means that the current labour market situation is not a new normal. We expect a period of normalisation to start with the end of high inflation and profit growth as the trigger. In fact, we already see some of this happening right now. But, we do expect the impact on unemployment and bankruptcies to become more visible in 2025, with a modestly increasing unemployment rate as a result. Similarly, with real wage growth recovering to pre-crisis levels, we expect a drop in wage growth also to occur in 2025.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article