Eurozone: Don’t mention the ‘r-word’ just yet

A reversal of some one-offs could bring slightly higher growth to the Eurozone in the second quarter, but the risks of US tariffs on European cars, as well as Brexit could yet be another brake on activity. With inflation unlikely to pick up much, there’s little need for monetary tightening from the ECB

The recession-word is back in vogue

With Italy having seen two consecutive quarters of negative growth and Germany just narrowly escaping it, the recession-word is coming back into vogue. While some temporary factors have held growth back, it is fair to say that the underlying trend points to a further growth slowdown with the risks tilted to the downside. However, it remains too soon to pencil in a recession in the Eurozone.

With 0.2% quarter on quarter growth in the fourth quarter, the same growth rate as in the third, the Eurozone seems stuck in a lower gear. While the Italian economy has probably been hit by tighter financing conditions on the back of the spreads widening on the bond market, the weak German growth in the second half of 2018 was probably a one-off, related to productions delays in the car manufacturing sector. When things get back to normal in Germany, we should see some growth acceleration.

The big question is whether things will really get back to normal. Some (temporary) improvement in the growth figures is still likely, but at the same time, a number of downside risks remain. The Brexit saga will continue to create uncertainty (with a potential hard Brexit likely to be a big drag on growth for a quarter or two). On top of that, the trade negotiations between the US and the EU seem to be going nowhere, raising the likelihood of higher import tariffs on European cars (see page 2). Also taking into account the negative sentiment effect, this could shave off 0.2 percentage points of Eurozone growth.

Eurozone growth slows further in January

Forward-looking indicators don’t bode well for first quarter growth

Meanwhile, Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann had to admit that Germany’s economic weakness carried into 2019. The first economic indicators for January also saw little improvement for the rest of the Eurozone. The European Commission’s sentiment indicator fell back further in January.

Forward-looking indicators like order books and production expectations in the more cyclical manufacturing sector don’t bode well for first quarter growth, while export order books took another hit. Industry mentioned a significant drop in the competitive position on foreign markets outside the EU, which is probably related to the relatively strong euro exchange rates in effective terms.

It is also telling that the share of managers who see their current production capacity as more than sufficient, increased considerably in January - a warning sign that business investment might start to cool down. On a more positive note, consumers have become slightly less worried about unemployment, which could support consumption in the months ahead.

Little evidence of rising inflation trend

There is no need for the ECB to start thinking about monetary tightening

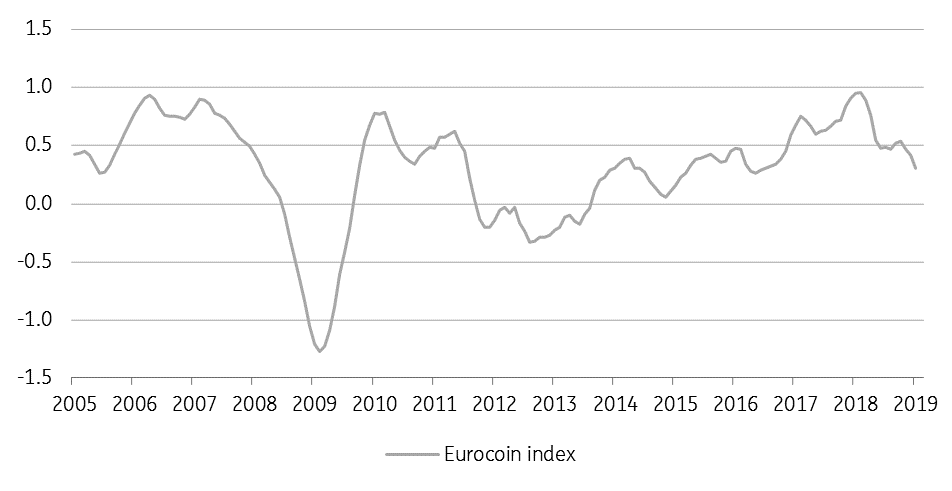

In January the €-coin indicator, a gauge of the underlying growth momentum, decreased to 0.31, from 0.42 in December, falling to the lowest level recorded since July 2016. While the first quarter is therefore unlikely to see much growth acceleration, we expect a minor growth pick-up in the second quarter. That should result in 1.2% GDP growth for 2019, revised downward from 1.4%. For 2020, we also expect 1.2% growth, so no recession yet, but definitely a slowdown from the growth rhythm we saw in 2018.

Despite the lower growth profile, the ECB is still convinced that labour cost pressures are continuing to strengthen and broaden amid high levels of capacity utilisation and tightening labour markets, which will generate an upward path in underlying inflation. A recent study from the ECB finds positive demand shocks foster this transmission, not exactly what we expect. On top of that, in an environment of low inflation the transmission tends to be slower. So, yes, underlying inflation could increase somewhat over the next 12 months, but we are probably not going to see 1.5% this year.

In that light, there is no need for the ECB to start thinking of monetary tightening. However, the ECB is not entirely insensitive to the fact that the long period of negative rates and a flat yield curve is having a negative impact on bank profitability, which could eventually result in tighter credit conditions (A study on the effect of negative interest rates on credit in Sweden). In those circumstances, a ‘technical’ 0.15 basis points deposit rate hike in the fourth quarter might still make sense, although the bank could also find other means to alleviate the banks’ burden, such as remunerating a part of the excess liquidity at the refi rate. Apart from that, we are increasingly convinced the ECB will come up with a new longer-term funding operation by June to avoid an increase in the banks’ funding cost. So, in sum, we think the ECB will take measures to avoid monetary policy tightening than to embark on a tightening cycle.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

8 February 2019

February Economic Update: Stick or twist? This bundle contains 9 Articles