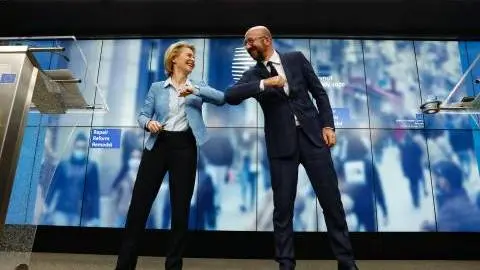

EU summit: A historic deal reached

A marathon negotiation has resulted in an agreement on the EU budget and recovery fund. It is a significant step of solidarity and integration, but the hard-fought negotiations show that this provides no guarantee of unity moving forward and it is unclear how much political porcelain has been smashed for good

They got it done at last. The agreement on the Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF) and the Next Generation EU recovery effort, including the Recovery and Resilience Fund (RRF) is a milestone for the EU as it tries to battle the economic impact of the corona crisis. This crisis has already seen quite a few sacred European cows toppled and this latest agreement marks the most significant one. The EU has already allowed countries to overrun the maximum allowed budget deficit, and borrowing can be done for short-time work schemes (SURE) and from the European Stability Mechanism without conditionality for coronavirus-related spending. The European Central Bank pulled out all the stops, allowing full flexibility in asset purchases, but that was all just a lead-up to the real game changer: the EU will now borrow in the market for grants to individual member states.

What’s been agreed?

A deal worth €1.824 trillion in total, including €1.074 trillion for the multi-annual budget for 2021-2027, including sizable increases in rebates for the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark and Sweden and an upheld rebate for Germany. The total size of the Next Generation EU recovery effort has been upheld at €750 billion (in 2018 prices) and the EU will borrow up to that amount on capital markets until 2026. The specific recovery and resilience fund receives €672.5bn, more than in the initial proposal, as a mix of €312.5bn in grants and €360bn in loans. The other programmes under Next Generation EU, including spending on innovation and greening, have all seen cuts compared to the initial proposal.

The allocation of the Recovery and Resilience Facility grants is upheld from last week’s Council proposal. That means that 70% gets disbursed in the first two years (2021-2022) according to a set key. Some 30% will be disbursed in 2023, depending on the depth of the recession in 2020 and cumulative GDP performance in 2020 and 2021. That amount will therefore only be calculated in 2022. Payment of grants will be conditional on progress made on national recovery and resilience plans that the countries have to submit, focusing mainly on the Commission’s country specific recommendations for reform and a jobs and growth agenda. The Commission will monitor progress and member states can escalate issues with other countries’ progress to the Council.

Is this the most effective recovery fund and budget possible? No, it isn’t. In terms of size, the fund is still relatively small given the severity of the economic crisis. Also, the fund will only become effective on 1 January, with the first money probably reaching the real economy not much before mid-2021. On top of that, there have been cuts to the original proposal on long-term investment funding such as research and development, digitization, greening and health. Still, given that more than a year ago a meagre eurozone budget was almost impossible and given how far apart member states had been at the start of the discussion, this morning's outcome is still remarkable. Even if it is what a soccer player might call a "dirty victory". It is not the result of unity and solidarity but rather a hard-fought compromise, and only time will tell how much of the drama has been for the voters at home and how much political porcelain has been smashed.

What does it mean for the economy and markets?

According to our preliminary calculations for the first two years, the maximum amount of grants disbursed from the RRF will be 1.6% of EU GDP at €218.75bn with large differences among countries. More vulnerable countries like Italy and Spain can receive grants for around 2.5% and 3.5% of GDP, while France, Germany and the Netherlands have maximum allotments of 0.9%, 0.4% and 0.5% of GDP over those two years, respectively. Especially for the countries that were more vulnerable going into the coronavirus crisis, this will provide a decent amount of stimulus to their economies. Many of those are also the ones with sharper economic downturns due to stricter lockdowns to curb the virus. However, don’t forget that the fund will only become effective next year and that 30% of it won't be disbursed until 2023. To tackle the economic impact of the virus now, the countries in need will and should lean on the options offered by the ESM, looser fiscal rules and the SURE (Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency) programme.

With hindsight, it might have been a better idea to actually separate the negotiations on the RRF and the MFF. The link was made in order to construct the issuance of a temporary common bond, without having to give it this name. Maybe the RRF should have been a eurozone project, rather than a EU-wide project.

The negotiations on the RRF have always had a pure economic dimension and a symbolic dimension. The fact that there will now be grants is an enormous step towards solidarity in Europe. The fact that there will be something like a common bond is an important step towards further integration, even if the impact should not be overestimated. It is still a one-time fund exceptionally created for the coronavirus crisis and the bitter fights at the Council show that it is not a given that future crises will receive a similar response.

Whether these significant steps, however, will have the maximum symbolic impact remains to be seen. From a positive perspective, the fact that government leaders negotiated to the bitter end to find a deal and did not simply decide to postpone the decision shows that all of them saw the sense of urgency. Also, the fact that Germany and France have been working closely together on all of this should have strengthened the markets’ belief in more integration. From a more negative perspective, the hard-fought compromise has not sent a signal of strong unity. Only time will tell which of these two perspectives will become the dominant narrative in financial markets.

One thing is for sure, while the ECB was the only game in town for quite some time now, it looks like a second team has entered the game. That should take some of the pressure off of the central bank in the aftermath of this historic crisis. And probably even more if the second team improves its team play.

Download

Download article

21 July 2020

Covid-19: The world’s slow, uneven recovery This bundle contains 8 ArticlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more