Dutch rent controls barely dent institutional investors’ returns

Recently introduced maximum rent increases in the private housing sector in the Netherlands has had a limited effect on the expected returns of institutional investors in the mid-market rental segment. The risk of future rent controls, however, may well be impacting negatively on returns

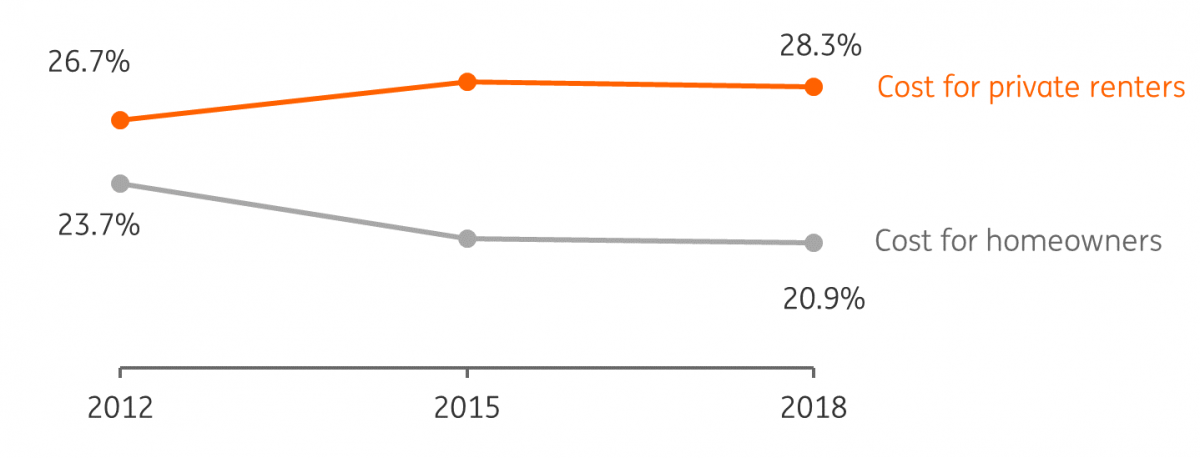

Further divergence in housing costs for private sector renters and homeowners

Housing costs for private sector renters in the Netherlands have increasingly exceeded those of homeowners since 2012. Nationwide, private sector renters (1) spent an average of 28.3% of their disposable income on rental costs in 2018. At 20.9%, the mortgage costs for homeowners were on average 7.4 percentage points lower. In 2012, the difference between the two groups was much lower, at an average of 3 percentage points. The share of homeowners’ money spent on mortgage payments has been declining since 2012, partly due to a further decrease in mortgage interest rates.

Increase in housing costs for private renters compared with homeowners

Net rental costs for private renters and net mortgage costs for homeowners, as a percentage of disposable income

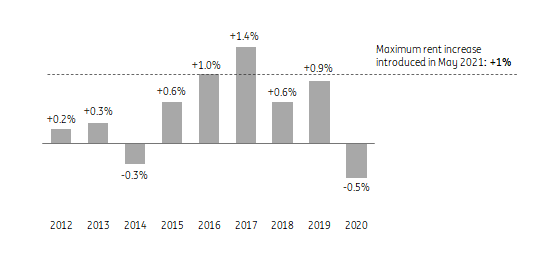

Maximum rent increase has limited effect on housing costs for sitting tenants in private sector

Since 1 May 2021, sitting tenants in the private sector have benefited from a nationwide maximum rent increase limited to inflation plus 1% per year (2). Although this limit is intended to decelerate the increases in rental costs for sitting tenants, it appears to have had only a negligible effect on rent affordability for these people. Apart from the fact that the limit is not aimed at the current rent levels but rather the annual rent increase for sitting tenants, the annual average rent increase for sitting private sector tenants in the Netherlands has almost always been below inflation plus 1% since 2012, even without the current limit (the real increase was only higher in 2017 at 1.4%). The maximum rent increase, therefore, does not help to reduce costs for private sector renters who are paying relatively high rents in relation to their income.

Increase in private rental sector rents mostly below 1%

Nominal rent increase adjusted for inflation in the previous year. Average year-on-year real rental price evolution in the private rental sector for sitting tenants.

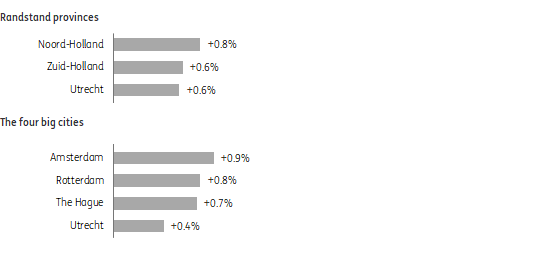

Maximum rent increase puts more of a brake on rent increases in private sector in Randstad

The majority – about 64% of all private sector rental properties in the Netherlands – are located in the Randstad conurbation, an area characterised by relatively high rental costs in the private rental sector. We will therefore also look at the expected impact of the limit on rent increases for sitting tenants in this region.

The introduced maximum in Randstad may go some way in slowing down the annual rent increase for sitting tenants in the private sector, as the average annual rent increase in this area in recent years has tended to exceed the introduced maximum. Nevertheless, the expected effect remains limited here as well. The average annual rent increase (CBS Statline data at a provincial level is only available for the social housing and private rental segments combined) was twice as much as 1% above inflation in Noord-Holland and Utrecht from 2015, but was below the maximum each year in Zuid-Holland.

In Amsterdam, the rent increase in four years was just above the maximum. However, the average annual real rent increase between 2015 and 2020 was well below 1% in all provinces. Amsterdam may be the exception, with an average real rent increase of almost 0.9% between 2015 and 2020 in the private sector and social housing lets. This is because the real rent increase in the private rental sector is generally slightly higher than the increase in social housing lets.

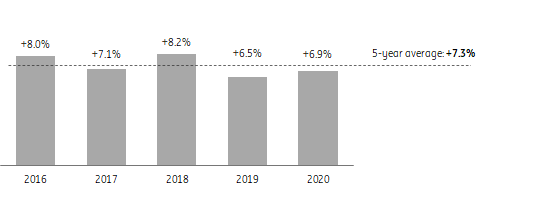

Rents rise by an average of more than 7% upon change of tenancy

Average real rent increase upon change of tenancy*

Rent increases concentrated among new tenants

The maximum rent increase only applies to tenants with an ongoing rental agreement, not to new tenants. There are currently no national regulations limiting initial rents for new tenants in the private sector, even though this group in particular has relatively high rental costs. This is because a change of tenancy often triggers rental increases that are on average far above the annual rent increase for sitting tenants.

For example, the real rent increase upon a change in tenancy (3) in 2020 was 7.3% on average. The large rent increases when there is a change of tenancy are the result of the increased shortage of properties in the private rental sector in recent years. For example, initial rents in the private sector increased by over 30% between 2015 and now (4).

Annually, approximately 15% of the rental properties in the mid-market segment (about 65,000 properties) and 23% of the properties in the high-end rental segment (about 25,000 properties) become vacant (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, 2021). In total, this amounts to more than 90,000 properties annually becoming available for new private renters. In particular, those who are looking to rent and only have the pick of properties in the private rental sector are increasingly struggling to find affordable housing due to the large rent increases.

Rents rise by an average of more than 7% upon change of tenancy

Average real rent increase upon change of tenancy*

Current maximum rent increase has limited effect on returns for institutional landlords

The recently introduced maximum rent increase focuses on the rental costs of sitting tenants and may also affect the return that institutional investors achieve on mid-market rental properties. If the maximum rent increase reduces their return, it may diminish their willingness to invest in the construction of mid-market rental properties. However, the current maximum rent increase for sitting tenants in the private rental sector appears to have a limited effect on returns. There are three reasons for this:

- The annual rent increase for sitting tenants was on average already below or only slightly above the current maximum and therefore does not usually trigger a significant rent increase. Various institutional investors confirmed this picture when surveyed. Prior to the limit being introduced, they had already been factoring in an annual rent increase at or below the set maximum for their business case for mid-market rental properties.

- However, institutional investors can continue to correct for inflation even with the limit in place. This is what largely determines their interest in the mid-market rental segment, as it contributes to the stability of their future rental income.

- As the current limit does not apply to initial rents for new tenants, large increases in rent are still possible upon a change of tenancy.

All in all, the above gives no reason to assume that the current maximum rent increase will significantly harm the returns of institutional investors in the mid-market segment.

Risk of future rent control may possibly harm returns

Uncertainties about additional rent control in the future may already be diminishing institutional investors’ willingness to invest in the mid-market rental segment. As institutional investors invest in residential property for the long term, regulatory risks play an important role when making investment decisions. The increased political awareness of the worsening shortage of affordable properties for middle-income households in the private rental sector has increased the risk of additional rent controls in the private rental sector.

The Dutch government, for example, is currently investigating the possibility of nationwide controls on initial rents for new tenants in the private rental sector, and various political parties advocated an expansion of the ‘Woningwaarderingsstelsel’ (housing evaluation system) points system in their latest election manifesto. In addition, municipalities (especially of the big cities) have for some time now been increasingly imposing requirements on initial rents and rent increases for new-build projects. Depending on their design, controls on initial rents can have a significant effect on institutional investors’ expected return on the construction of mid-market rental properties. Investors will be considering these risks of future controls in their current investment decisions.

References

- Private and institutional landlords with 44% of owned property rented as ‘private rental’ in 2018 (PBL, 2019).

- The maximum applies for a period of three years. For 2021, the maximum nominal rent increase is set at +2.4%.

- Average increase upon change of tenancy in the social housing and private rental sectors.

- Development from 2015 up to and including the first quarter of 2021, based on average rents per m2 as listed on Pararius (Dutch online property directory).

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article