CEE Sovereigns: Where we stand on EU funds

CEE sovereigns Poland, Romania, Hungary, and the Czech Republic have been reliant on inflows of funding from the European Union in recent years, but political disputes have brought into question the eventual timing and size of future disbursements

EU Funds: CEE-4 Cheatsheet

EU funds are of huge benefit to CEE sovereigns

EU funds have been vital for sovereigns in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) in recent years in terms of funding public investment, boosting growth and providing stable inflows of foreign currency to finance current account deficits. CEE countries have, in general, seen around 1-3% of GDP annually in inflows of EU funds over the past decade from the structural and cohesion funds of the bloc's multiannual budget framework.

This can to some extent be shown by the capital account in the balance of payments (that shows capital transfers to governments) for these countries, and these funds have tended to be somewhat cyclical, rising in their absorption towards the end of the EU budget cycle (for example, in 2014-15, when the 2007-13 funds could still be accessed due to the so-called ‘T+2’ rule) before some dropoff in the transition period from ‘old’ to ‘new’ EU budgets, as seen in 2016. With 2023 the last year when the previous round of funds can be used (2014-2020 budget, T+3 deadline), 2024 should be another important ‘transition’ year for countries such as Poland and Hungary that are yet to unlock funds from the new budget.

CEE annual capital account balances

% of GDP

Across CEE, there are differing extents to which governments are reliant on EU funds, while the recent shocks from Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine have naturally increased their overall importance, given tougher conditions for market-based financing. Within the CEE economies, Romania’s persistent twin deficits (current account and fiscal) would leave it in a somewhat vulnerable position absent EU funds, given the combination of EU transfers and FDI inflows can be seen as stable sources of financing for the nation’s current account deficit.

At the same time, from a fiscal perspective, EU money is used to fund vital public sector investment. This situation appears to be generally reflected in the government’s attitude towards EU funds and broader EU relations, with the EU framework seen as a key economic policy anchor. In Hungary, last year’s energy shock caused a sharp widening in the current account deficit and brought the need to unlock EU funds into focus. For Poland and the Czech Republic, the focus is more on the impact on public investment and GDP growth prospects, with less external sector vulnerability.

CEE select balance of payments measures

% of GDP, 5-year average

EU funds: The current situation

Alongside the latest round of structural and cohesion funds under the EU’s 2021-27 multi-year budget, more funds have been made available for European sovereigns in the form of grants and loans from the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) in response to the Covid crisis, along with more recently the REPowerEU plan to reduce dependence on Russian energy. The wide-ranging ‘Rule-of-Law’ disputes for Poland and Hungary, in particular, have increased investor uncertainty over the potential timing of new disbursals of EU money, while the backdrop of the EU’s plans for the green transition will likely mean increased investment needs for the region as a whole. In this context, the topic of EU funds is likely to remain at the forefront of CEE investors’ minds in the coming months and even years.

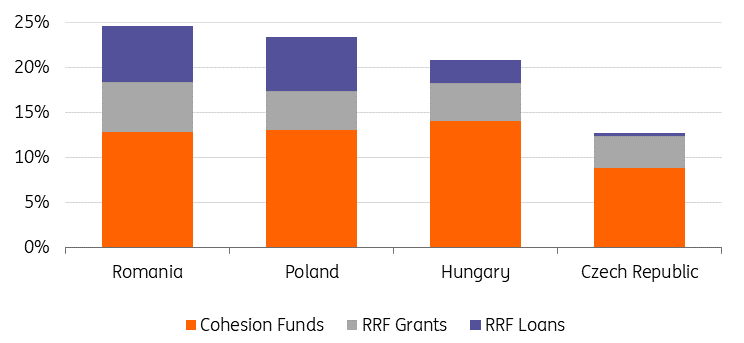

The sums of money at stake for CEE sovereigns are significant, with around 20-25% of 2021 GDP expected to be transferred or lent to Poland, Hungary, and Romania in the coming years across the Cohesion Funds, RRF, and REPowerEU. This figure is smaller for the Czech Republic.

Planned EU funds for CEE countries by programme

% of 2021 GDP

Country level expectations

Poland

We warned about a possible drop in EU fund inflows to Poland in 2024 in a Think article a year ago. While following the T+3 rule, Poland has continued to disburse EU funds from the ‘old’ EU budget (2014-20 financial perspective) this year, there is a significant risk that disbursements will drop significantly from early 2024.

This is because the money from the ‘old’ budget will be almost exhausted (some final settlements are still possible early next year), while the money from the ‘new’ EU budget (recovery fund and 2021-27 cohesion funds) will remain untapped due to no progress on the Rule-of-Law regulations. If this issue is unsolved in the coming months, it will negatively affect PLN and Polish bonds.

According to Year-to-Date Ministry of Finance data up to the end of August this year, Poland got €5.9bn from the EU’s cohesion and structural funds, of which €5.2bn is from the ‘old’ budget and €0.7bn comes from the ‘new’ budget. The latter constituted some advance payments for project preparations and technical assistance rather than proper project funding.

Because Poland signed contracts fully made up of the available EU allocations from the ‘old’ budget (data as of late September) but disbursed 87% of funds, the remaining funds will continue flowing through to the end of this year. We estimate the remaining amount to be disbursed is almost €10bn.

But if Poland makes no progress on the Rule-of-Law, the country will not be able to disburse EU funds from the ‘new’ budget from early 2024. The judiciary reforms constitute so-called super (or horizontal) milestones in RRF, and no payments can be based on the sectoral milestones. These judiciary provisions are also relevant for disbursements of cohesion funds from the ‘new’ budget as one of the enabling conditions requires compliance with the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, which includes independence of the judiciary.

Elisa Ferreira, the EU commissioner for Cohesion and Reforms, made it clear in a press interview last week that the European Commission will not disburse any invoices from Poland’s new cohesion funds if the enabling conditions are not in place.

There is a risk of a sudden halt to the inflow of EU cohesion funds

In our view, there is a risk of a sudden halt to inflows of EU cohesion funds from the 2021-27 budget, which is a different case than the already-expected significant drop in EU funds in a transition year in disbursements from 2013-2020 and 2021-27 EU budgets. A significant slowdown occurred in the previous transition year, 2016. Grants from RRF could fill the gap to some extent (if unlocked). However, no progress on judiciary regulations creates a risk of a sudden stop for inflows of cohesion funds in early 2024. The payments related to the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP) of nearly €5bn annually are not at risk as they are part of EU-wide programmes.

In our optimistic scenario, with RRF and ‘new’ cohesion funds in place, Poland would see a small drop in overall EU funds in net terms (inflows of all EU funds less Poland’s contribution to the EU) from about 1.5% of GDP (average in the recent three years) to about 1.0% of GDP in 2024. However, in the pessimistic sudden 'stop' scenario, with the Poland-EC agreement delayed to mid-2024, the net inflow of EU funds to Poland in 2024 may decline to around zero.

Hungary

At the moment, 100% of EU funds are at risk amid the ongoing Rule-of-Law debates. The report related to horizontal enablers (four judicial reforms) was sent to Brussels on 18 July. With this, a net 90-day window opened for the European Commission to challenge or accept the changes. This time window works like a chess clock; thus, it is set at the start of the game (when Brussels got the report) to count down from the agreed time (90 days) and paused after an action by the EC.

The European Commission stopped the net 90-day review period for the Hungarian government's implementation of legislation on 25 September, when it asked nine questions on the implementation of judicial reforms. This means that until the government provides further evidence of the implementation of the reforms, the 90-day clock remains on pause. According to our calculations, there are still three weeks left on the clock, and that clock will start ticking again as soon as the reply arrives in Brussels.

The likelihood of a deal diminishes with each passing day

As a practical matter, even in the most ultra-optimistic scenario, this means the earliest the green light could be given is the end of October. However, bearing in mind that even after the government provides further evidence, the EC has the power to stop the clock again if it asks for even more evidence. In general, the likelihood of a deal this year diminishes with each passing day. Overall, however, we remain optimistic that a partial agreement will be completed before the end of the year.

In 2023, the budget risk from EU funds is 1% of GDP (revenue stream planned from RRF in this year’s budget). Once Hungary solves RRF conditions (the so-called 27 ‘super milestones’), everything will be released, but this is the hardest part. If the latest judicial reforms (which form part of the RRF requirements) are accepted by the EC, it can potentially open up access to up to EUR 13bn of Cohesion Funds.

Discussions on a technical level work with Hungary, but politics is the problem; news reports have highlighted potential Hungarian support for increasing the EU budget and further aid for Ukraine as related topics of negotiation. These latest reports also suggest the EU could unlock this part of the Cohesion Funds by the end of November, which would support our view of a slight delay to the initial mid-October deadline. This first step would be crucial to remove some risk premium from Hungarian assets, although the remaining €9bn of Cohesion Funds, along with the grants and loans from the RRF and RePower EU, would remain blocked until the full implementation of the RRF 'super milestones'.

Romania

Romania is in a better position theoretically than Hungary and Poland in the sense that there are no funds at risk. Not achieving some milestones from RRF could diminish the tranches, but that does not seem likely right now.

In the latest update, Romania had to update the NRRP and cut 2.1bn of investments because of better-than-expected economic performance in 2021. However, a new chapter has been added – Repower EU, worth €1.4bn. So, the total amount of the plan diminishes by only €700m.

The new plan is currently with the EC and should be approved soon. The payment of the 2nd tranche (€2.8bn) of the RRF was paid at the end of September. The third tranche worth €1.8bn was initially due on 31 December 2023, but given this intermediate step in updating the NRRP, will probably be delayed by some three months.

The special pensions issue is a hot topic

The “special pensions” issue is a hot topic for the third tranche, with the EC requesting pension reform. A planned bill was rejected by the Constitutional Court and is now back in Parliament. It is worth mentioning that the form of the law is currently exceeding EC’s requests. Cutting it down somewhat (by excluding magistrates from its applicability, as per the Court’s request) is likely to still comply with EC requests. The Commission hopes to have the conditions met by the end of the year, with money disbursed in the first quarter of 2024.

Czech Republic

In terms of GDP, the allocation of EU money and the RRF is the smallest in the CEE region, so it is not as big a topic as its peers. The country has had no problems so far with the Rule-of-Law and we don't expect any such problems in the near future. The original RRF plan envisaged €7.7bn in grants only without using loans. The government asked for an update on the RRF plan in June, and the EC confirmed it in September. The total size was increased to €9.2bn (€8.4 in grants and €818 million in loans).

The original amendment proposal included more loans, but MinFin later decided not to use this facility due to limited EUR needs, expensive hedging and a lack of projects on paper. The first RRF payment request was made in November last year, and around €900m was paid in March this year.

The market implications

The CEE region has seen a volatile few years for its hard currency bonds. From previously being a relatively safe haven in the EM space, the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine saw a more significant geopolitical risk premium priced into the region, which was added to by concerns over the European energy crisis and its impact on fiscal and external accounts.

This means the average spread on sovereign dollar bonds across the CEE (here using Poland, Hungary and Romania) widened from 50-75bp tighter than the average for Investment Grade EM sovereigns pre-2022 to now between 25-50bp wider.

CEE USD bond spreads vs EM IG average

Basis points

With headline geopolitical risks somewhat reduced for the region, along with an easing in the energy crisis for Europe, it’s clear an additional catalyst is needed for CEE Eurobonds to return to their longer-term, pre-2022 average spread levels (in particular on a relative basis compared to other IG sovereigns). Progress towards fully unlocking EU Cohesion Funds and the RRF could be supportive for a further recovery in the Eurobonds of the region as a whole, along with on a country-specific basis, given the likely reduced uncertainty over sovereign credit ratings and macro stability in general.

EM sovereign net issuance of international bonds by region

On a related issue, the state of EU funding could have significant implications for the outlook for Eurobond supply from the region. For much of the past decade, the Middle East and Africa (MEA) have been the dominant forces behind net international bond issuance for Emerging Market sovereigns, while net issuance has even been negative for Hungary and Poland for several years. Since 2020, however, we have seen a slight pickup in net issuance from CEE in USD markets, given high local rates and energy financing needs.

This trend is likely to continue in the coming years, given increased spending needs (whether related to energy and the green transition, military expenditure or social needs), as evidenced explicitly in Poland's latest plans for borrowing. Further delays to EU funds could add to the need for structurally higher net Eurobond issuance, a further technical factor that could weigh on the secondary market performance of outstanding bonds.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article