Brexit: Seven big questions looming in 2018

The announcement of 'sufficient progress' removes a big layer of uncertainty for markets and the UK economy, but there are still a number of big questions looming in 2018

Progress at last

After months of deadlock, the EU and UK have finally reached a deal which allows the European Council to declare 'sufficient progress' to move onto trade talks. The UK has reportedly agreed to meet all of the financial commitments set out by the EU earlier this year. They have also accepted that the European Court of Justice will have a role to play in policing citizens rights, formally a big red line for the UK government.

But the big sticking point was the Irish border. The wording agreed earlier in the week, which committed to "no regulatory divergence" on the island of Ireland, raised fears within the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) that this could weaken Northern Ireland's access to the UK internal market. But a series of additional commitments - including one that guarantees "unfettered access" for Northern Ireland to the overall UK market - appears to have reassured the DUP.

Now these 'divorce issues' are resolved, here are the seven things we'll be focusing on in 2018.

Is a transition deal now a given?

Almost. Now that the European Council has agreed 'sufficient progress' has been made, this should allow for a fairly swift agreement of a two or three year transition period after March 2019. There is increasing consensus that businesses need confirmation of this by March 2018 if they are to avoid enacting contingency plans for a 'cliff edge'. That should be possible, mainly because the more controversial elements of the transition - abiding by EU law and allowing free movement - have already been accepted by the UK. Equally, several legal matters also need to be resolved, so it may not be until later in the first quarter when the transition is agreed on paper.

Either way, the agreement of a transition would be a positive for the UK economy as it should help unlock at least some short/medium-term investment.

Will a two or three year transition period be long enough?

A big fear of Brexit-supporting ministers is that the transition period could lead to an indefinite period where the UK is neither in nor out of the EU. This is partly because the next election is scheduled for 2022, and an extended transition could leave the government vulnerable to suggestions it hasn’t brought the UK entirely out of the EU.

But does this give firms enough time to adjust? The complexity of modern supply chains means many goods often travel multiple times between the UK and EU before being sold in the single market. The BMW Mini and pints of Guinness are good examples. These processes will take time (and money) to re-orchestrate.

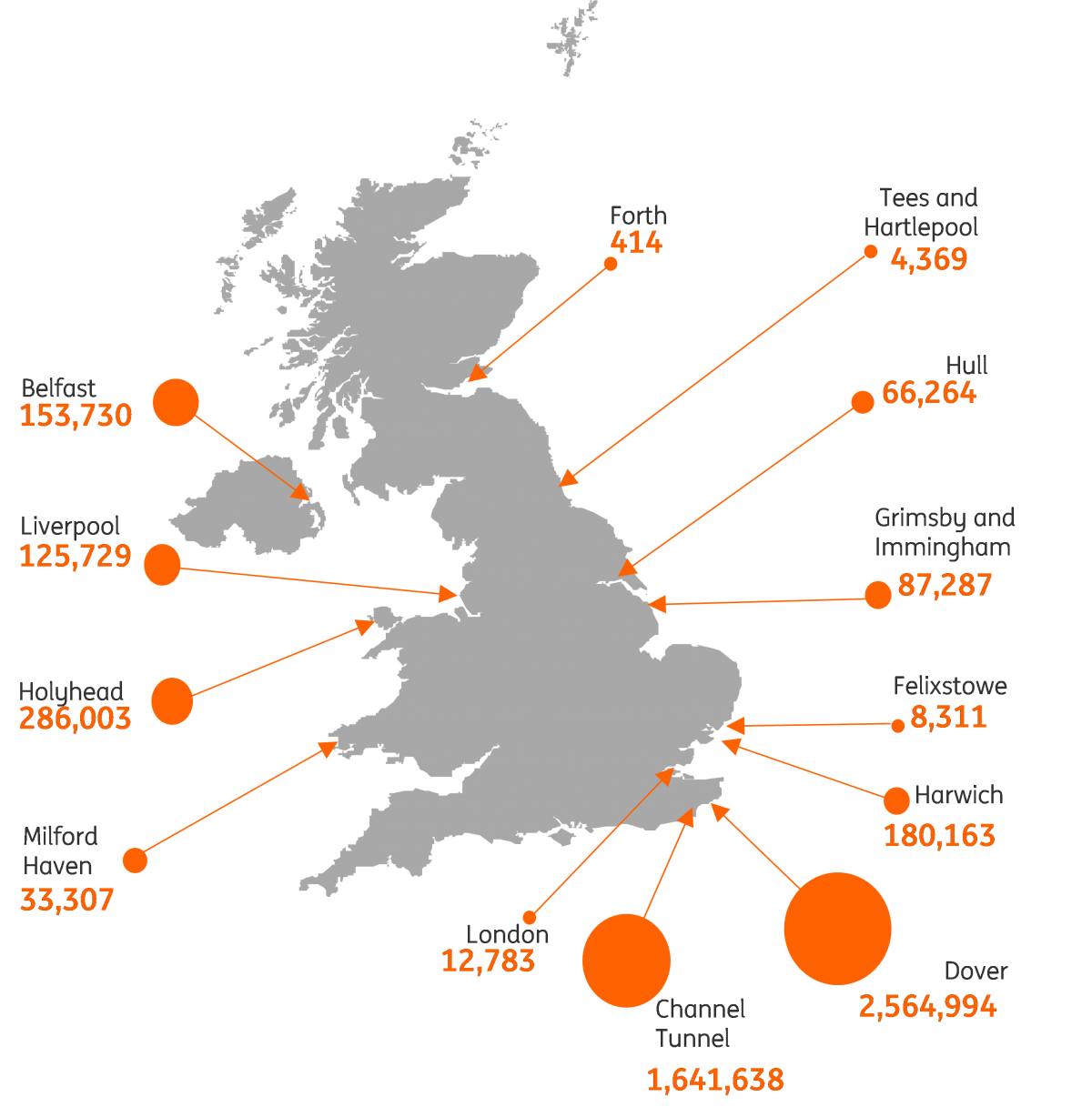

Logistics are also a big consideration. At Dover, less than 1% of lorries arriving and departing require checks[1]. Given the sheer number of lorries that pass through, maintaining a frictionless border will be key. The British Freight Transport Association has said that adding even two minutes to the process could generate queues of up to 17-mile queues on the M20 motorway. Part of creating a fluid customs process will require new staff, but this too takes time. For instance, it takes three years to train a new customs official in Germany, and two years in France.

[1] Implementing Brexit: Customs (Institute for Government report)

Of course, there is the potential for the transition period to be extended. If negotiations take longer than expected, it is unlikely that the UK government would walk away and trigger "cliff edge" Brexit having worked so hard to avoid it this time around.

While this may upset the most hardline of Brexiteers, the government compromises made so far suggest they are increasingly acknowledging the need to minimise the threats to the economy and jobs.

Lorry traffic at selected UK ports (no. of lorries)

Will there eventually be a deal?

Given the volume of trade done between the UK and the EU, the impacted supply chains, the millions of jobs and tax revenues, a deal makes sense for both sides.

The UK position has already softened on the divorce bill and the role of the European Courts of Justice and it seems as though they are also edging back from the "no deal is better than a bad deal" scenario. The EU is also recognising the importance of getting a positive agreement for both sides by acknowledging the need for a transitional period. Nonetheless, the actual trade discussions will be tough and protracted, but two factors cargue in favour of a mutually beneficial deal.

Firstly, the worst case scenario of no deal and the adoption of World Trade Organisation Rules would introduce tariffs on trade. On average they amount to 2-3%, but a wide range of food products will be hit particularly hard. This could see upward pressure on prices and a further squeeze on spending power. But the key issue is the wide criteria. For example, the full US trade schedule contains 192,275 different lines of tariffs, which means companies can face tough choices on optimising their production processes if they have to import multiple different types of components. Dispute settlement also takes a long time - typically a year and up to 15 months if there is an appeal - a period during which trade can be heavily impacted.

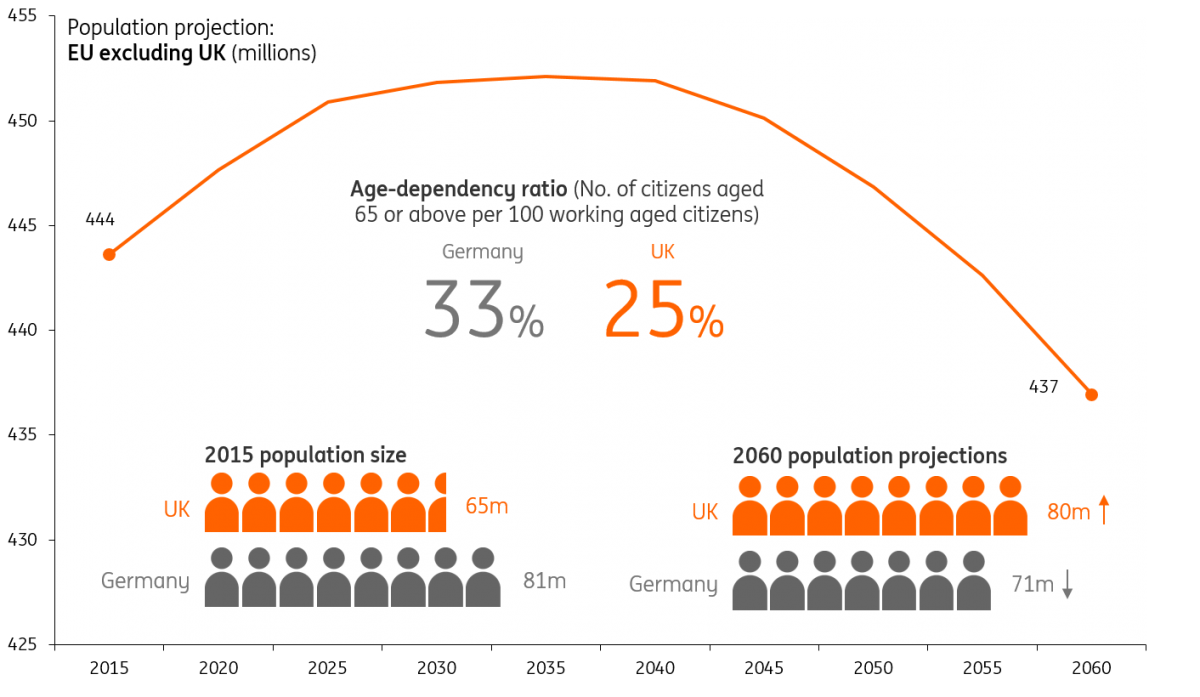

The second reason that argues for a positive deal is demographics. The fact that birth rates have declined across the EU, means that Europe's population is set to fall over coming decades. However, in the UK the birth rate has increased in recent years, fuelled by immigration. Consequently, the EU predicts that the UK is set to overtake Germany as Western Europe's most population nation within the next 20 years. From the EU's perspective, having access to a growing market that is on its doorstep and is cheap to export to clearly makes sense, particularly when the domestic market is being squeezed.

Demographics give an extra incentive for a deal

When will the UK and EU agree a trade deal?

Now that some of the more thorny issues of the Brexit process are resolved, PM May will reportedly sit down with her cabinet over the coming weeks to try to agree on a "model" for the trading relationship by the spring to give businesses a better understanding of the direction of travel. After that, the UK government’s official position is that it expects to strike a trade agreement before exiting in March 2019.

But taking off three to four months for ratification leaves less than a year to agree on a deal, which is a very short timeframe. So it’s possible that at least some elements of the talks will continue into the transition period. One consequence of this is that, without a concrete idea of what trading environment the UK will actually be transitioning into in 2021 or 2022, companies are likely to remain cautious when it comes to longer-term investment even after a transition is announced. Until details emerge, this effectively means the 'cliff edge' risk is still present, albeit two or three years later. It's worth remembering too that, in the EU's words, "nothing is agreed until everything is agreed".

What will the trading arrangement look like?

'Imaginative', 'creative' and not 'off the shelf' were all phrases used by Prime Minister May in September to describe the bespoke trading arrangement she'd like to agree with the EU. The European Economic Area (EEA) option would require free movement (a big red line). The free-trade option, like the Canada-EU deal, would get around this by allowing the UK to control migration, and enable it to strike separate trade deals with other countries. But crucially, access to services (including finance) is notoriously difficult to negotiate as part of free-trade deals. This is why David Davis is now talking about the need for a "Canada plus-plus-plus" arrangement that includes services, which accounts for more than 70% of the UK economy.

So can the UK agree on a half-way house? Well, clauses embedded in existing free-trade deals mean that whatever the EU offers the UK on services, it would also have to offer to other countries that it already has agreements with (Canada and South Korea for example). This means there is a reduced incentive for the EU to offer the UK a bespoke deal, which makes it more likely the UK will ultimately have to choose between the Canada-style free-trade agreement or the EEA.

Will Prime Minister Theresa May stay?

Since the general election in June, PM Theresa May’s position is perceived to have weakened. This has led to questions over how long she can remain in office, particularly as opinion polls were suggesting the public is dissatisfied with the government’s handling of Brexit.

The fact that the Prime Minister has been able to reach an agreement with the EU on 'sufficient progress', having navigated a delicate path within her own party and with the DUP, could help to repair this image. By and large, the government has also successfully avoided a large fallout over the politically-sensitive 'divorce bill', and the first opinion poll after the announcement of the deal has seen the Conservative's popularity bounce. They now have a narrow lead of one percentage point over Labour.

Nonetheless, PM May remains vulnerable, and a fresh leadership challenge in 2018 can’t be fully ruled out should negotiations falter. We also have to recognise that there is always the potential for a by-election to be called as there are typically four to five a year. So given PM May's wafer-thin majority the government could still fall, paving the way for new elections.

Will the Bank of England hike again in 2018?

While the announcement of a transition deal should unlock some short-term business spending, there are still some Brexit ‘ifs’. The jobs market is also showing early signs of faltering, which could limit the potential for a takeoff in wage growth next year. This will keep a lid on consumer spending, and in turn, overall 2018 growth.

Another rate increase is therefore not guaranteed, although policymakers have signalled they would be comfortable with a hike next year. A move in February or May certainly can’t be ruled out, particularly if a transition is swiftly agreed.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

13 December 2017

ING’s outlook for 2018 This bundle contains 7 Articles