Brexit: non-event or knockout blow to EU recovery?

The economic impact of a no-deal Brexit on the EU economy will be significant, with tariffs introduced and disruption for some sectors likely. The automotive industry, agriculture and chemical sectors stand to be the most affected

Negotiations on a post-Brexit trade deal have proven tough over the course of this year. While both sides have been inching closer to an agreement over recent weeks, last week’s EU summit reaffirmed that there's still a lot left to be resolved. Despite Boris Johnson's signal that he is prepared to walk away from talks completely, negotiations are expected to resume in one form or another over coming days.

Our house view is that there will be a deal agreed, but time is running out and both sides realistically have until the middle of November. That means there is still time for things to go wrong, and the risk of there being no deal, or only a wafer-thin agreement, are uncomfortably high.

Border checks concerns are about to become reality

The main issue that has spooked people over the past few years has been chaos at the borders as border checks would suddenly come into effect. The British Freight Transport Association has estimated that every extra minute a lorry spends at the border for customs checks, will result in an additional 30km of queues along the major roads to Dover. Current expectations are delays of up to two days for outbound shipments to the EU, according to Michael Gove, the UK minister responsible for Brexit.

These queues drive up transport costs as transit times will be longer. Businesses reliant on just in time (JIT) supply networks will also see inventory costs go up as they will need to hold larger buffers of spare parts. And trade of fresh agricultural goods could be badly affected if long delays emerge as the time that perishable goods can be sold is limited.

For EU exporters to the UK, the immediate effects of a no-deal Brexit would be less severe. This is because the UK would phase in checks over a period of three to six months in a no deal scenario. EU exporters will initially only need to prepare for basic customs requirements on most goods going into the UK, and this should help minimise some of the disruption at key roll-on-roll-off ports for goods entering the UK.

Fig 1: Most exposed EU sectors to trade with the UK

Share of EU sector output destined for the UK as either intermediate or final products /service.

We computed the share of EU sector output that depends on trade with the UK. This is output in intermediate and final products destined for the UK. This exposure may be through indirect exports as well. For example, output of the chemicals and plastics industry in car exports to the UK. Taking all of that together shows the share of output of a sector at risk of possible disruption. The automotive, chemicals and electronics sectors are the most exposed to trade with the UK. These sectors are also characterised by more complex supply chain networks that potentially include multiple border crossings between the EU and the UK due to imported intermediate inputs. This means that these sectors will see the largest increase in costs as the rise in trade costs will accumulate with every border crossing.

For example, more than 80% of UK cars are made for export. However, these cars include a lot of imported parts on which the EU and the UK will also impose tariffs in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

Due to the current economic contraction related to the COVID19 pandemic, there is already slightly less trade than usual. This may offer some relief at the border, and potentially may see slightly reduced disruption than otherwise would have been the case.

At a country level, the risk of possible disruption differs significantly between countries[1]. Looking at the larger EU economies, then Belgium and Netherlands are high on the list of countries that depend on trade with the UK and are therefore at risk of experiencing larger fallouts from the increased barriers to trade that will happen as of 1 January.

Fig 2: For most EU countries, dependence on trade with the UK is less than 4%

Share of EU country output destined for the UK as either intermediate or final products /service.

The country level exposure shown in Figure 2 may also come from indirect trade with the UK. For example, the exposure of Germany may be in part through German car parts in Slovakian car exports to the UK.

Agricultural products and cars will be most heavily taxed

Another key issue if trade negotiations fail is that tariffs will come into effect on 1 January. Currently there are no tariffs on trade between the EU and the UK. In a no deal scenario, EU imports from the UK would be taxed at the EU’s WTO tariffs. In such a scenario, the UK will also impose tariffs on imports from the EU. The UK government has already published the tariff schedule which it will apply in case of a no-deal situation. The UK will not simply mirror the EU tariffs and has announced that for a lot of products, tariffs will be kept at zero. Still, there would be significant tariffs on a large number of goods (See Figure 3).

This is especially true for (processed) agricultural products, with tariffs as high as 150% on some dairy products. This means that exporting to the UK will become a lot more expensive for the EU agricultural sector, if no trade deal is reached. Other product categories with high tariffs are textiles and cars (included in transport equipment) adding to worries for an already volatile sector.

Fig 3: UK tariffs by product group (weighted by imports from the EU)

The countries facing the highest trade-weighted tariffs are Ireland, Greece and Slovakia. The high trade-weighted tariff of Slovakia is mostly associated with a high share of cars in Slovakian exports to the UK. For Ireland, this is a double whammy. Not only is the UK its largest trade partner, it also exports goods on which the UK asks particularly high tariffs.

One caveat, however, is that Irish-UK trade is unsurprisingly linked to Northern Ireland. As part of the Withdrawal Agreement, Northern Ireland will remain a de-facto member of the EU customs union. That therefore means that for trade confined to the island of Ireland, tariffs will not apply.

Larger EU countries such as France, Germany and Italy have a more diverse export basket and are therefore facing lower tariffs on average (for more detail see Figure 4).

Fig 4: UK’s trade weighted tariff by EU country

For outbound trade from the UK to the EU, the EU’s WTO tariff schedule will apply. The EU’s tariffs are a bit higher than those proposed by the UK. Although these tariffs will still be fairly low, importing goods from the UK will become more expensive for EU businesses. The EU's tariffs are highest for agricultural products and the automotive industry. This raises input costs for firms with UK based suppliers.

Invalid product certifications may complicate supply networks

When the transition period ends, the UK will leave the single market and, in principle, that means British product rules could change. Without a deal, that potentially means products that require certification, such as safety equipment, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals will need to be tested/certified on both sides of the channel.

To some extent, the immediate disruption for EU exporters has been mitigated by the UK’s decision to recognise the CE mark for all of 2021, and has signalled no immediate plans to change most product regulations. But ultimately, EU firms will need to have dual conformity assessments in place to meet both European (CE) and UK (UKCA) rules.

However, the challenges are more immediate for sectors where the conformity requirements are stricter. The FT has recently highlighted the example of the chemicals industry, which faces the imminent and expensive task of re-registering individual products, with-or-without a deal (although an agreement would potentially remove some of the barriers to re-registration).

In short, all of this is time-consuming and expensive for businesses and will complicate trade for many more EU exporters.

Contingency measures needed for services in case of no deal

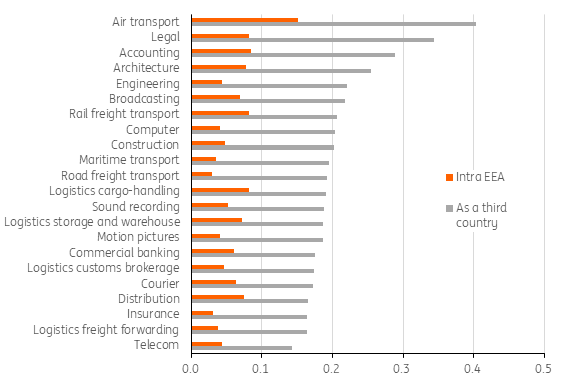

Deal or no deal, Brexit will have a significant effect on services. Free-trade agreements typically do very little for services – and Brexit is set to herald a range of changes covering issues from licensing to data-sharing and freedom of movement restrictions. Figure 5 shows the difference in barriers for trade in services within the European Economic Area and with third (non-EU member countries). Without any deal, the UK will face the same restrictions as other third countries.

Fig 5: Intra EEA and extra EEA barriers to services trade

Due to the intangible nature of services, there are various ways for businesses to deal with these restrictions. For example, contracts can be adjusted to include new terms for data sharing with non-EU countries and businesses can register overseas subsidiaries to operate across border.

That said, a deal would have some benefits. Firstly, it would likely trigger a deal on financial services equivalence (a much narrower version of passporting), as well as a data adequacy agreement. It would also presumably involve a deal on aviation, while it could also resolve the potential issue stemming from a shortage of truck licenses for UK hauliers that travel to Europe.

On the issue of transport, back in 2019 both sides announced contingency measures to allow basic air travel and trade to keep moving in the event of ‘no deal’. Similar arrangements have so far not been formally replicated for the start of 2021, keeping businesses and passengers in an uncertain position for now.

The immediate impact will be significant for the EU, though less noticeable due to Covid-19

It is hard to argue that a no-deal Brexit, and all the changes that would bring on 1 January, are a non-event for the EU economy. Disruptions to supply chains, thanks to border checks, will be small initially but could become an issue after a few months. Tariffs will be raised on numerous EU goods and disruption to trade in both services and goods requiring new certifications is a risk if no contingency measures can be put in place. This will mainly affect agriculture, automotive and the chemical industry, with countries like Ireland, Belgium and the Netherlands likely to experience the most disruption due to the relatively sizable amount of trade between them and the UK.

As a result of the large economic volatility caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the economic impact will not be as noticeable as it would have been if a 'cliff-edge' Brexit had occurred last year at growth rates closer to zero. Make no mistake: the introduction of tariffs, disruptions to supply chains and the risk of other non-tariff related disruption will have a negative impact. In a recent literature review by the European Central Bank, the longer term impact on EU GDP growth is estimated at -0.2 to -0.3%% in a WTO scenario, which will be higher at the beginning due to initial disruptions mentioned before. Together with large downside risks related to the second wave of the coronavirus, a no-deal Brexit will make for a very volatile start to 2021 for the EU economy.

Download

Download article23 October 2020

Second wave, second chance? This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articles"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).