Brexit: The risk for trade in services

A victory for Prime Minister Boris Johnson at next month's election would mean his Brexit deal is likely to be ratified. But there's still a chance that the UK could see an abrupt end to the transition period in December 2020. That wouldn't just be bad for trade in goods. There's a risk that barriers to trade in services could more than double

The UK could still abruptly exit the single market and customs union, even if a deal is ratified

UK PM Boris Johnson is hoping that a comfortable lead in the polls will help him to secure an outright majority in December’s general election. If he succeeds, we think that will give him the numbers to get his deal ratified by Parliament early in the new year, potentially enabling the UK to leave the EU at the end of January.

But while that would avoid a damaging ‘no deal’ exit early in 2020, there are big question marks over the length of the transition period. This standstill period lasts until the end of 2020, unless the UK commits to paying into the next multi-year EU budget.

Brussels wants this tied up by the end of June, and a failure to do so would raise the risk of an abrupt end to the transition period, which would see the UK (with the exception of Northern Ireland) leave the single market and customs union. Ultimately, we think an extension is probably inevitable, but if we’re wrong, the effect on trade in goods and services between the EU and the UK would be similar to that of a ‘no deal’ Brexit.

Trade in services at risk

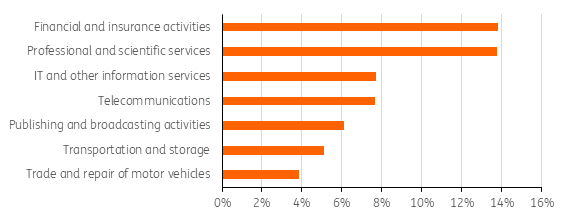

The consequences of a no-deal Brexit for goods often draws the most attention. But, for trade in services, an abrupt exit from the EU's single market would have major implications as well. Many UK services depend significantly on cross-border demand from the European Economic Area[1] (EEA) (figure 1). The top three industries that are most dependent on cross border trade in services with the EEA account for 22% of UK GDP. Total UK GDP dependent on cross border trade in services with the EEA is 4.2%.

[1] Barriers for trade in services are the same for all EEA countries, which are the EU, Norway, Switzerland, and Iceland.

Figure 1: Seven most dependent services sectors on cross-border EEA business (UK)

What are the consequences of a 'no deal' exit for these industries? First of all, restrictions in the movement of people make cross border services trade more difficult. However, much more is at play. Unlike with merchandise trade, there are no such things as tariffs levied for the imports of services. But non-tariff barriers for services trade can be detrimental as well. Different standards, permit and labelling requirements, non-recognition of foreign qualifications, and migration restrictions can be major barriers for trade in services.

Passporting for trade in financial services

A particularly important aspect of the European single market for the financial services sector is ‘passporting’. ‘Passporting’ means that a bank or other financial firm that has obtained authorisation to conduct business in one EU country, is free to do business in any other EU country as well. Financial firms can apply for different passports for different types of services. These range from insurance and corporate banking (fourth capital requirements directive) to facilitating financial market transactions (MiFID).

Passporting has helped London to become the biggest financial centre of Europe. Currently, demand by the EU for financial services accounts for 14% of the UK banking and insurance business. A 'no deal' Brexit or failure to achieve a free trade agreement after Brexit would end (apart from some temporary exemptions) these passporting rules and restrict the type of services that can be provided by UK firms to EU clients.

The UK has introduced a 'temporary permissions regime' to allow EEA firms to continue operating if no deal is agreed. However, depending on the rules that the UK imposes in the longer-term, there could ultimately be some restrictions on the services that European financial firms can provide in Britain.

Economic pain inflicted by new barriers in the financial services sector is not limited to the sector itself. A dismantling of economic ties between London and European financial markets could also reduce access to foreign capital and invalidate financial arrangements that some firms rely on.

Trade barriers will also hit beyond financial services

In addition to finance, ‘professional and scientific services’ significantly depend on cross border trade (see figure 1). This includes legal services, accounting services, R&D and Architecture. To a lesser extent, Telecommunications, IT and publishing and broadcasting services significantly dependent on final demand from the EEA. Trade in all of these industries rely on the mutual recognition of standards, licenses and qualifications.

Some of the major professional qualifications that are affected are accounting, chemistry, engineering and architecture.

Mutual recognition of professional qualifications is laid out in two EU directives. If the UK leaves the EU without a deal, or leaves the single market after the transition period, these directives become invalid. This means that UK professionals have to apply for recognition in individual EU countries. If a UK professional is recognised in one EEA country, this recognition will not be automatically valid in others. Some of the major professional qualifications that are affected are accounting, chemistry, engineering and architecture. These barriers would also affect EEA firms that would like to do business in the UK.

A lot of restrictions implied by a no-deal Brexit or similar scenario are sector or service specific. Law experts will be needed to advise service providers on how to deal with the new rule book. This means the cost burden for service exporters will rise, making them less competitive. One way that UK firms could deal with these restrictions is by establishing a subsidiary within the EEA. The subsidiary would then fall within EU jurisdiction.

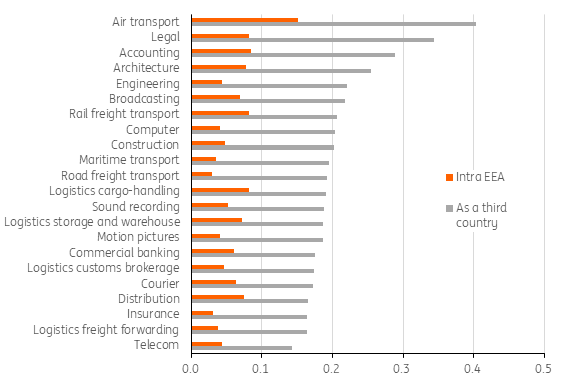

The OECD quantifies barriers to trade in services, distinguishing between countries within the EEA and non-EEA countries. Using the relative importance of the individual EEA countries to UK services trade we computed a weighted average for each sector. Figure 2 shows the difference in barriers faced by UK service sectors when part of the EEA (orange) or as a third country (grey).

Figure 2: Intra EEA and extra EEA barriers to services trade (export weighted)

All sectors in figure 2 face a doubling or more in trade barriers for services in the case of a no deal Brexit or failure to establish an FTA before the transition period is over.

These barriers won't only hurt the sectors they concern. Spillover effects (also non-services) are a danger to the overall economy. To mitigate some of the worst chaos, the EU and UK governments have already started to amend certain agreements such that they remain valid (for some time) after the UK has left the EU (without a deal). Some of the major steps taken are:

- Aviation: legislation has been put in place such that for an interim period (until 4 October 2020) air traffic between the EU and th UK can continue until a final deal is arranged. (Regulation (EU) 2019/502).

- Road freight and passenger connectivity: the EU extended current legislation facilitating basic road freight and road passenger connectivity to 31 July 2020 (Regulation (EU) 2019/501).

- Clearing houses and UK security depositories: Various measures for the UK to retain access for some time to the EU markets in case of a no deal Brexit.

- Derivatives: Implementation of rules that allow, for some time, the transfer of certain financial contracts to the EU.

Firms will have to look for ways to deal with the new rule book that follows a no deal Brexit. One way of dealing with some of these barriers could be to establish subsidiaries in EU countries or to have employees obtain qualifications in EEA member countries. The uncertainty surrounding the post-Brexit rule book will weigh on investment in the UK and Europe.

"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).