Brexit’s back

There's growing talk of the EU suspending its trade deal with the UK, should the British government make unilateral wholesale changes to the Northern Ireland protocol. That would revive the risk of a 'no deal' scenario, but fresh Brexit uncertainty may actually not have as big a market impact as perhaps presumed. Expect EUR/GBP near 0.8500 at year-end

Nothing says that we’re in the run-up to Christmas more than Brexit negotiations - and this year seems to be no exception. The UK is threatening to escalate the tensions with Brussels that have been simmering away for months. The risk is that we head back to square one where the threat of ‘no deal’ looms large once again.

So far, financial markets have largely shrugged this off. After all, for all the negative headlines this year, the UK has mostly avoided upping the ante over recent months, while the EU has been careful to keep the door open to negotiations. And given the trade deal agreed last year was only one notch up from not having a deal at all, the economic impact of further escalation is probably seen as more limited.

But this calculation could soon be put to the test. The UK government is poised to usher in wholesale changes to the Northern Ireland (NI) protocol – that’s the part of the 2019 deal that guarantees no hard border on the island of Ireland. The Article 16 safeguard clause allows either side to unilaterally suspend parts of that agreement in the event of major economic disruption – a threshold the UK argues has been met.

What happens next depends how much of the NI agreement the UK suspends

That Article 16 will be triggered is viewed as increasingly inevitable, but what happens then is far less clear. What ultimately matters is how far the EU decides to retaliate against any UK action. And that initially depends on exactly how much of the Northern Ireland protocol the UK government seeks to suspend.

A narrow move by the UK to rectify a specific issue – perhaps aimed at making life easier for supermarkets bringing products from the British mainland into NI – need not provoke a nuclear response from Brussels. That’s particularly true if London follows the correct procedure laid out in the original deal, and continues to carry out other checks on goods entering NI. The clause says that the EU could take retaliatory measures, but only that are ‘proportionate’ and ‘strictly necessary’, and linked directly to the Northern Ireland agreement itself.

Recent comments from Brexit minister Lord Frost suggest that might be wishful thinking. The government wants fundamental changes to the way the protocol works, and it seems more likely, therefore, that Article 16 is used to suspend large parts of the agreement. Trying to unilaterally tinker with the role of the European Courts of Justice – which can weigh in on disputes surrounding the protocol – would be viewed as particularly incendiary in Brussels.

The EU has various options at its disposal, some of which we’ve detailed in the infographic below. But to cut a long story short, many of the legal options offered by the different agreements signed with the UK are either very long-winded, potentially taking years, or could constrain how far Brussels can respond. A rapid imposition of tariffs, through these routes at least, may be difficult.

The EU's options for retaliation if the UK triggers Article 16

The EU could decide to suspend the trade deal in a worst case scenario

That’s why there's an increasing number of reports suggesting the EU could look beyond the traditional arbitration systems on offer.

For instance, the part of last year’s trade deal that covers fishing allows for access to French waters to be suspended or tariffs to be introduced on UK goods with seven days' notice, should the EU believe the UK is breaking the rules there (though it’s not clear that this test has been formally met).

Member states could also make life more difficult for UK firms, perhaps by stopping the free flow of data between Britain, or just by simply checking a higher proportion of goods heading through EU ports.

But as we’re increasingly hearing in news reports, the EU can also suspend the whole agreement with 12 months – or nine if only the trade aspects of last year’s deal are scrapped. Needless to say, if this were to happen, we’re back into the realms of ‘no deal’ and so-called ‘WTO terms’.

None of this necessary spells disaster for the pound

On paper then, an increased layer of uncertainty and the reintroduction of a negative economic tail risk is bad news for UK markets. But there are a few reasons why the return of Brexit may not be dramatic for sterling.

Firstly, even if the EU does decide to serve notice on last year’s trade deal, clearly there’s an intermediate window where most likely there would simply be more negotiations. Prime Minister Boris Johnson has twice now swerved away from ‘no deal’, both in 2019 and 2020, and markets may well assume he will eventually do a last-minute deal this time too. Rightly or wrongly, the UK may be gambling that it can use the 9-12 month period to demonstrate that its version of the NI protocol is operable and therefore unlock greater concessions.

Secondly, the economic hit if there were to be an abrupt end to the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) may not be gigantic. That may sound naïve, and it would undoubtedly deal a sharp blow to a few key sectors – most notably agriculture where tariffs tend to be extreme, but also for the likes of the car industry.

The return of Brexit may not be dramatic for sterling

But remember that much of the cost burden associated with Brexit comes from form-filling and customs processes, which are already in place. To qualify for zero tariffs under the current deal, companies need to prove that their products have sufficient EU or UK content to qualify, which can be very expensive in itself. In some instances where tariffs are low, it may already simply be easier to pay a tariff than document a supply chain.

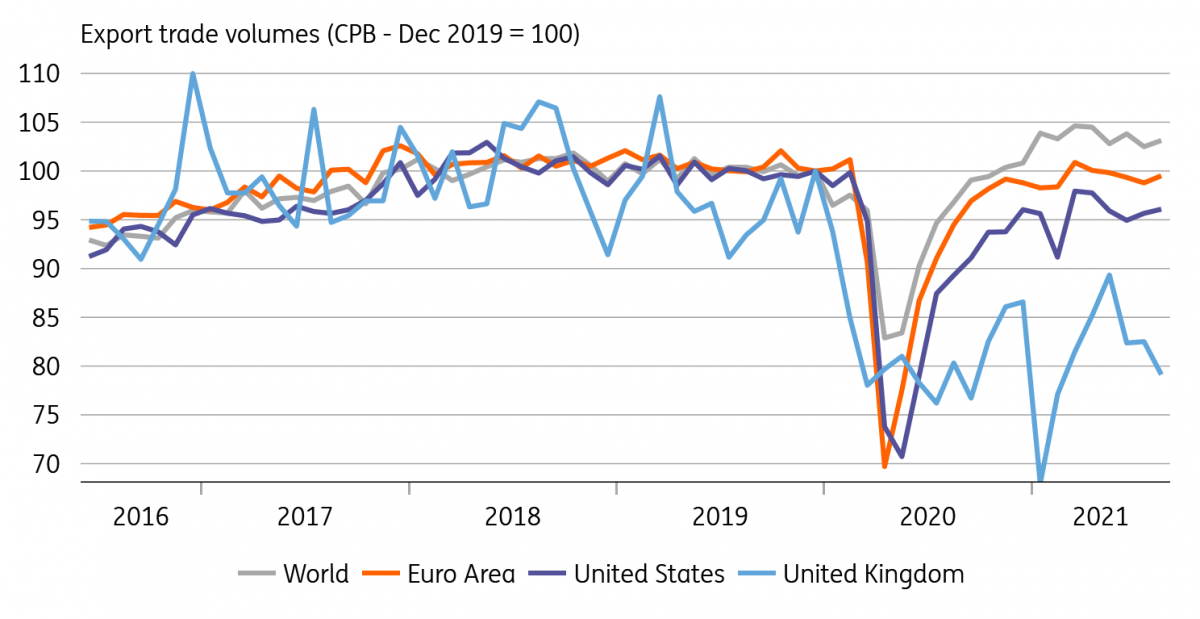

These frictions are undoubtedly showing through, even if exports have recovered a lot of ground since the start of this year. Data from the Dutch CPB suggests Britain is still lagging the overall recovery in world trade. And long-term uncertainty surrounding the UK-EU relationship is probably largely ‘priced in’ to corporate investment decision-making already.

UK exports are lagging the recovery in world trade

Many of the costs of Brexit have already been accrued

In short, the effect of leaving the single market and customs union at the end of 2020 was the major sea change in trade terms. The additional economic effect of reverting to ‘no deal’ on top of that may not be as considerable as perhaps supposed.

The final question for markets is whether any of this will change the calculus at the Bank of England – and the answer is probably not much. It is another reason to think that policymakers will hike rates more gradually than markets have recently been expecting. But the situation in the jobs market, and establishing how widespread labour shortages are, will be far the biggest determinants of what the Bank does.

Governor Andrew Bailey has recently reiterated that the Bank 'will have to act' if inflation expectations rise, and we therefore suspect policymakers will go for a hike in December, or at the latest, February.

GBP: Holding its own

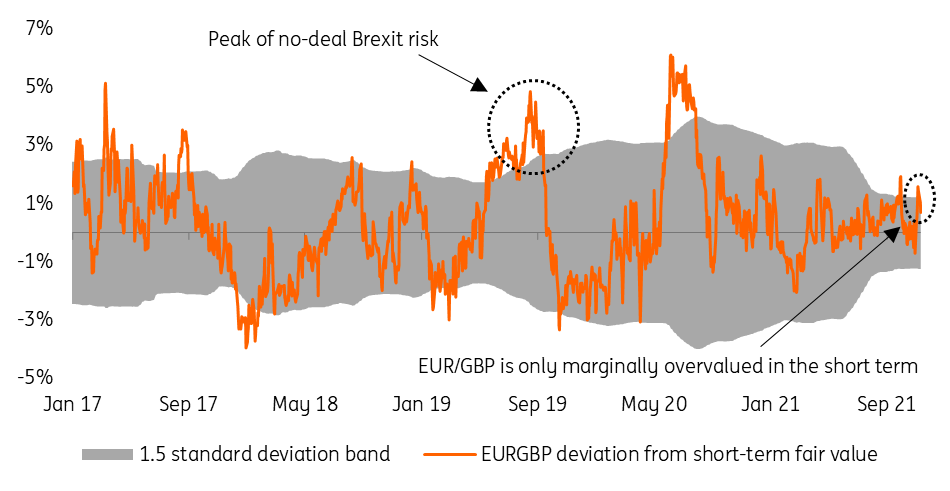

Reports of sterling's demise feel a little exaggerated to us. Before the autumn energy price shock/|BoE response episode, we had noted that GBP had withstood low-level Brexit noise well recently. Over the years, we have tried to gauge risk premium in the pound by using a Financial Fair Value (FFV) model - i.e. where EUR/GBP should be trading based on short-term financial variables. This year, that risk premium in the GBP has seemed quite contained - at about 1%. See the chart above.

Could another round of Brexit headlines demand the kind of 5% 'no deal' risk premium seen in 2019? We suspect the impact on GBP is more muted this time around. And with UK CPI heading to the 5% area into April, keeping BoE tightening prospects on the front-burner, we are happy with an end-year EUR/GBP target near 0.8500, and lower levels as 2022 progresses.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article