Brazil: Post-strike pre-election blues

Higher inflation, lower growth and new evidence of fiscal profligacy have damaged investor sentiment towards Brazil. Political uncertainties suggest those concerns could intensify ahead of the October elections. Market intervention should help offset, but not eliminate, downside risks to local assets

More inflation, less growth

Recently released data helped provide a clearer assessment of the economic impact of the truckers’ strike, which took place at the end of May. Following the strike, the most notable side-effects included the 1.3% surge in inflation in June, and the broad-based contraction in economic activity in May, during the strike.

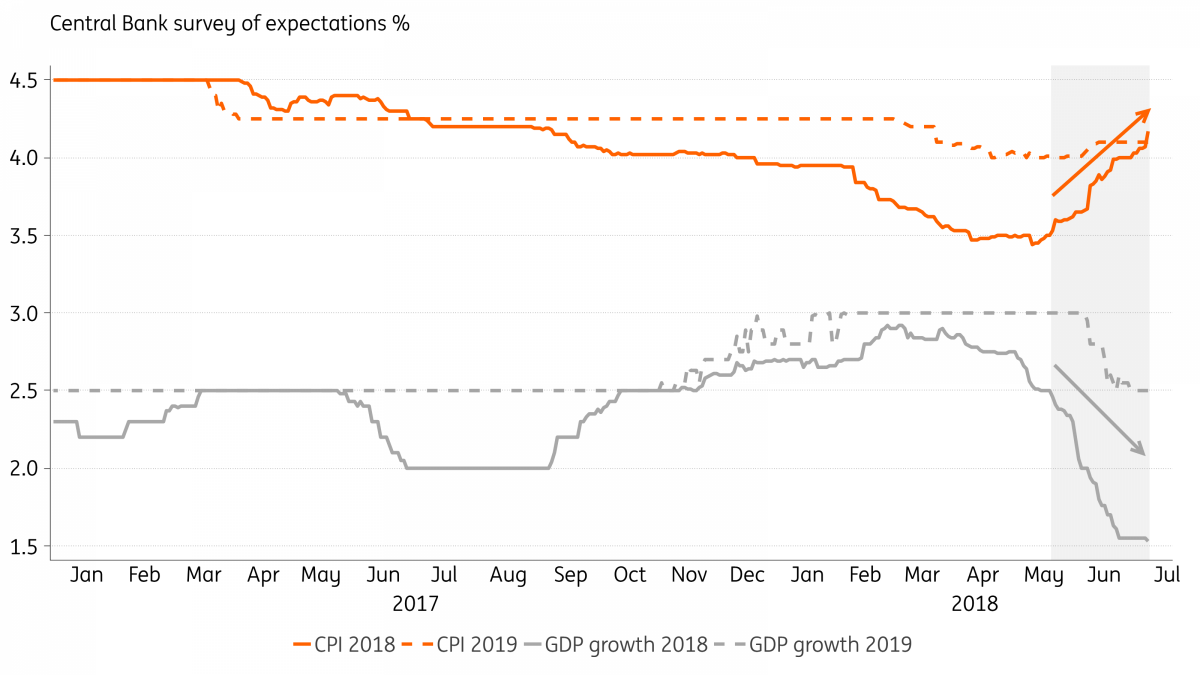

Much of the shock should be temporary, with upcoming releases for inflation and activity indicators likely normalising, as already evidenced by some leading indicators. But the swift deterioration in expectations for both GDP growth and inflation, as seen in the chart below, suggest sizable and more persistent after-effects.

Strike was a catalyst for major correction in Brazil's macro outlook

Our GDP growth forecasts (1.5% in 2018 and 2.5% in 2019) are fairly aligned with consensus, but we suspect there’s more deterioration to come on the inflation front. Consensus estimates for inflation in 2018 (4.15%) and 2019 (4.10%), as seen in the chart, remain materially lower than our forecast of 4.5% for both years.

This reflects our less constructive FX outlook, among other concerns such as: 1) the increase in transportation costs triggered by the decision to set a minimum price for truck freight, 2) the larger increase in the minimum wage, which is set to rise 4.6% in January 2019 vs 1.8% in January 2018, and 3) the consolidation of a higher range for inflation, up from a 2.8% YoY average in the past 12 months to 4.7% over the next 12 months, which threatens the favourable inertial impact seen so far this year and risk further deterioration in expectations.

Regulated prices have also surged, now tracking 12% year on year in June, in large part due to the sharp rise in fuel, cooking gas and electricity prices. And relief is unlikely in the nearer term, given the high oil prices, FX weakness and the typical seasonality for electricity prices.

Overall, this suggests that the truckers’ strike was a catalyst for a more persistent deterioration in Brazil’s macro outlook, beyond its immediate impact on prices and activity. It was a catalyst for higher risk aversion, with long-lasting consequences than initially thought, amid rising fiscal and political concerns, tighter credit conditions and greater caution on the part of borrowers and lenders.

A temporary reprieve for the Real

The recent stability in the dollar helped stabilise the real and allowed the central bank to temporarily halt its ad-hoc FX intervention program, after record-levels of intervention seen in June. But we remain bearish about the BRL, and still, consider the currency to be among the most vulnerable emerging market currencies.

As we discussed in Brazil: Buying time with intervention, a weaker BRL is fully justified by Brazil’s precarious fiscal accounts and the challenges any new administration would face reversing its explosive debt trajectory. As such, we expect the BRL to preserve a weakening bias amid prospects for continued demand for FX hedge. And so long as prospects for electing a market-friendly candidate in the October Presidential election remain dim, we consider the equilibrium level for the USD/BRL to be closer to 4-4.2, ahead of the October 7 race.

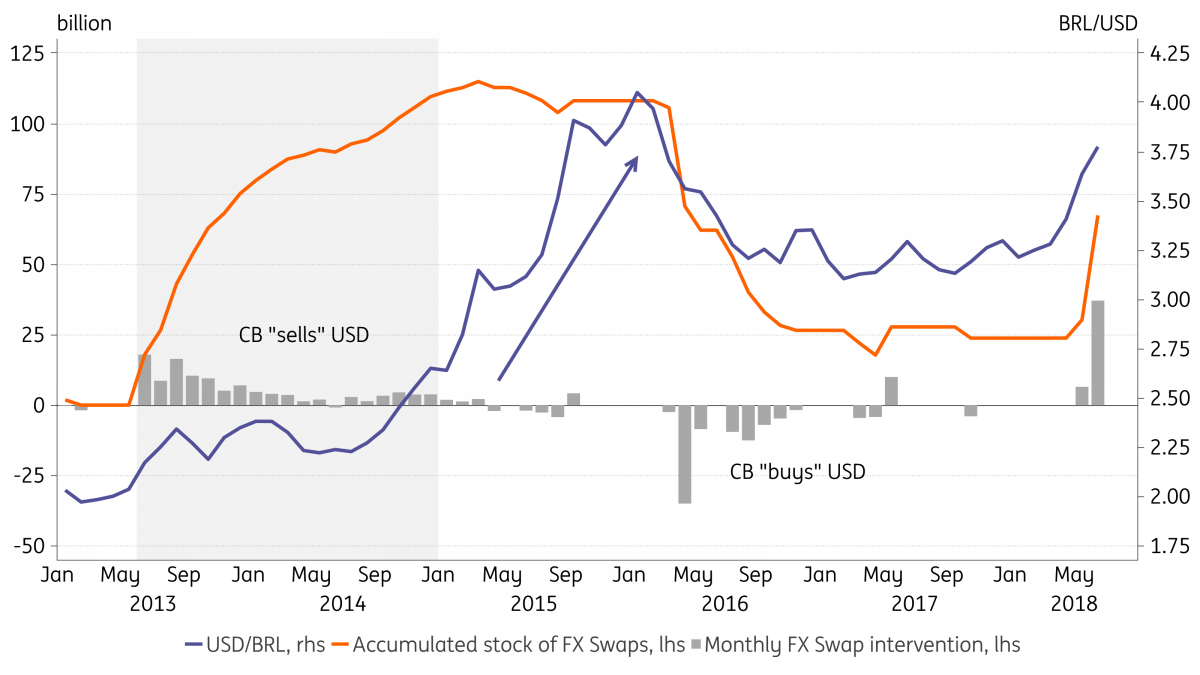

Brazilian officials continue to vow to fight any “excessive” depreciation in the real with FX intervention. But, in our view, intervention does not eliminate the downside risks to the BRL. As the recent underperformance of the BRL suggests, the heavy intervention in June (totalling US$37bn) served mostly to delay the currency’s adjustment

Ammunition for intervention through FX swaps may not last until the elections

Gauging the precise timing for the FX correction remains difficult, as it should depend on a catalyst (domestic or external). But if external conditions remain relatively benign, a new round of BRL weakness may take place only by late-August or September, with polls continuing to show that non-establishment candidates are more likely to win the Presidency.

BACEN still has substantial ammunition to provide FX liquidity, notably an additional US$50bn in FX swaps to reach the previous high seen in early 2015 (see chart above). But, in our view, intervention is more effective in its initial stages, and given its limited nature, may be depleted (or become ineffective) sooner than the three months until we know who Brazil’s next president will be.

A hawkish monetary policy shift is likely in September

If we are right in our FX assessment, the inflation outlook is also bound to suffer, with material upside risk for inflation expectations and for the central bank’s inflation forecasts.

In particular, a USD/BRL above 4, coupled with additional rises in inflation expectations, would place the central bank’s 2019 inflation forecasts materially above the 4.25% target for that year in all scenarios that consider this more depreciated level for the BRL. As a result, we now expect a shift in the monetary policy guidance, from neutral to hawkish, as early as September.

This is a scenario that policymakers are not yet prepared to consider in their upcoming monetary policy meeting, on August 1. For now, disappointing activity indicators, the considerable slack in labour markets and well-behaved core inflation indicators, such as the new core estimates recently highlighted by monetary authorities, should reinforce prospects for a stable policy rate (at 6.5%) in the foreseeable future.

Ultimately, however, we suspect this policy guidance underestimates the risk of a sooner-than-expected rate hike. Policymakers would frame any hike as an effort to anchor inflation expectations, which has become a critical indicator to monitor. Any suggestion that a hike was a direct reaction to FX weakness would be firmly refuted.

The biggest risk to our more hawkish monetary policy call would be a surge in voter support for an establishment candidate (such as Geraldo Alckmin). A market-friendly electoral result would trigger a BRL rally and provide substantial scope for the policy rate to remain in expansionary territory for a prolonged period.

Political update: All eyes on party-level negotiations

With the candidacy of some centre-leaning candidates gradually being abandoned, electoral dynamics are taking clearer shape. Flávio Rocha (PRB) left the race over the weekend while Rodrigo Maia (DEM) has effectively, albeit not officially, abandoned his candidacy. Maia seems to be focused on negotiating support for his permanence as Lower House President and on state elections.

The low voter support received by Henrique Meirelles (MDB), João Amoedo (NOVO), or even Álvaro Dias (PODE), raises questions about their viability, possibly resulting in alliances with other candidates. For instance, Dias and Meirelles have been mentioned as possible VP picks for Geraldo Alckmin (PSDB).

Leading candidates have the fewest campaign resources suggesting material room for volatility in voter preference in the coming months, but if what we’ve seen recently in Mexico and Colombia is any indication, anti-establishment sentiment may continue to prevail over campaign resource advantages

It is also increasingly evident that former President Lula da Silva is unlikely to be allowed to participate in the race. The PT seems likely to insist on having a presidential candidate, however, with Fernando Haddad likely running as Lula’s substitute. Supporting Ciro Gomes in a united leftist front seems to be off-the-table for now. Alckmin appears meanwhile to be firmly in command of the PSDB party, despite the preference of some within the party for João Dória, who is hoping instead to become São Paulo governor.

A key source of uncertainty lies now on party decisions regarding alliances. Alliances are critical because they help determine the campaign resources a presidential candidate will have at his/her disposal, including direct financial resources through the “party” and “electoral” state funds and the allotment of free TV/radio advertising, that begin airing on August 31. Coalitions are also key to determining the candidate’s exposure in local election events (rallies) and through the use of local party machinery.

Each party has until August 5 to hold their conventions and determine their candidates/coalitions. Alckmin’s inability to rise in the polls (so far) has prevented some ideologically-aligned parties in the centre to fully embrace his candidacy, creating additional uncertainty about the final composition of party alliances.

Investor focus is particularly concentrated on crucial negotiations with the centre-leaning parties, led by DEM and PP, in addition to the PRB, SD and the PR. These parties tend to be grouped under the “broad centre”/”big bloc” umbrella that controls almost 20% of the TV/radio ad time. The group met again over the weekend, but it appears that a final decision was not yet reached.

Despite the deep ideological divide that separates them, Ciro Gomes (PDT), who is vying for the title of leader of the left, and Geraldo Alckmin seem to be the two most competitive contenders for the support of these parties. A united front in support of either candidate could alter the race in a material way.

In particular, if they choose to support Gomes, local assets would likely sell-off, given the candidate’s perceived lack of commitment to fiscal austerity. Support for Alckmin, which we see as more likely and, to some extent, already incorporated into asset prices, would meanwhile be seen as mildly supportive for local assets.

Marina Silva (REDE), who typically ranks second in voter preference, appears to favour going it alone, instead of risking association with other parties. This effectively means that Marina will run with a skeletal campaign infrastructure, including minimal TV/radio exposure.

The frontrunner in the polls, Jair Bolsonaro (PSL), and the PT party, also appear, for different reasons, to be competing for a much more limited party support network. Bolsonaro is focused on securing the (still uncertain) support of the centrist PR party, while the PT is negotiating with small leftist parties.

The first presidential debate has been scheduled for August 9 (Band) but the campaign officially kicks-in in mid-August. The impact of campaign resource advantages is more likely to be felt during September however when the establishment hopes to close the gap with the anti-establishment amid the flurry of TV advertising that starts airing on August 31, up until the October 7 vote.

Alckmin remains the best-positioned “establishment” candidate to try to close that gap. Marina Silva could, meanwhile, see her support dwindle amid meagre exposure relative to the other candidates. Bolsonaro’s unusually effective use of social media and committed base suggests however that, despite his limited resources, he should remain a formidable force during the campaign.

Leading candidates have the fewest campaign resources suggesting material room for volatility in voter preference in the coming months, complicating assessment over the election's outcome. But if what we’ve seen recently in Mexico and Colombia is any indication, anti-establishment sentiment may continue to prevail over campaign resource advantages.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article