Australia: From saviour to victim

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Australia was viewed as a possible solution for energy shortages in the Asia Pacific region – instead, it has suffered its own energy crisis

Where does Australia want to be?

Australia has given a weak, non-legislated pledge to achieve net-zero carbon by 2050.

What it's been doing to get there: New 2030 goal announced

In October 2021, just prior to the COP26 climate round, Australia set out an intention to achieve net carbon zero by 2050. This was a weak commitment, however, not backed up by legislation and instead reliant upon AUD$80bn of technological expenditure by the government with the aim of creating a cost environment conducive to the adoption of clean energy. There was no change to the target for CO2 reduction by 2030 – making Australia one of only four economies making no reduction at COP26. The Australian government at the time said it would exceed existing targets (though by less than the 45% scientists believe is necessary to hit COP targets). Australia also said that it will continue to provide the rest of the world with the energy it demands, so there are no plans to phase out coal or gas extraction. Since then, the incoming Australian Labour government has pledged to reduce Australia's emissions by 43% by 2030 (almost 45%), which would become its new target under the Paris agreement.

What’s happened since the Ukraine war

The first point to note is the change in government at the Australian General Election on 21 May. The former Liberal / National coalition was beaten at the polls by Australia’s Labour Party, with the Green Party also picking up four total seats (three more than it had) on a 10.4% share of the vote.

With an overall majority, Labour will not need to lean on the Greens to pass policy changes, but as the position paper “Powering Australia” indicates, renewables have been pushed up the political agenda with this change in leadership and there is a new, more ambitious target for emissions reduction by 2030.

The key points of the new policy are:

- Upgrade the electricity grid to fix energy transmission and drive down power prices.

- Make electric vehicles cheaper with an electric car discount and Australia’s first National Electric Vehicle Strategy.

- Adopt the Business Council of Australia’s recommendation for facilities already covered by the Government’s Safeguard Mechanism that emissions be reduced gradually and predictably over time, to support international competitiveness and economic growth – consistent with industry’s own commitment to net-zero by 2050.

- Protect the competitiveness of Emissions Intensive Trade Exposed industries by ensuring they will not face a greater constraint than their competitors.

- Allocate up to $3bn from Labour’s National Reconstruction Fund to invest in green metals (steel, alumina and aluminium), clean energy component manufacturing, hydrogen electrolysers and fuel switching, agricultural methane reduction, and waste reduction.

- Provide direct financial support for measures that improve energy efficiency within existing industries and develop new industries in regional Australia through a new Powering the Regions Fund.

- Roll out 85 solar banks around Australia to ensure more households can benefit from rooftop solar.

- Install 400 community batteries across the country.

- Demonstrate Commonwealth leadership by reducing the Australian Public Service’s own emissions to net-zero by 2030.

- Invest in 10,000 New Energy Apprentices and a New Energy Skills Program.

- Establish a real-world vehicle fuel testing programme to inform consumer choice.

- Work with large businesses to provide greater transparency on their climate-related risks and opportunities.

- Re-establish leadership by restoring the role of the Climate Change Authority, while keeping decision-making and accountability with the government and introducing new annual parliamentary reporting by the minister.

Australia is one of the few clear net energy surplus economies in the Asia-Pacific region. And it has benefited from a positive terms-of-trade shock to its energy exports, in particular natural gas, but also coal following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Australia is also a major net exporter of agricultural products, including those directly disrupted by the war in Ukraine (wheat, corn), and also of metals.

There has been some talk of Australia providing more natural gas to Asia, thus freeing up other suppliers, such as Qatar, the US, and Algeria, to supply Europe with gas, displacing their reliance on Russian gas.

The reality is that the Australian gas export market was already operating virtually at capacity. New trains required for liquefaction of gas to enable LNG transport are not on the table. New gas fields, the Beetaloo Basin in the Northern Territory, the Barossa gas field off the coast of the NT, and the Scarborough field, north-west of Exmouth, will not start to deliver gas until 2025/26.

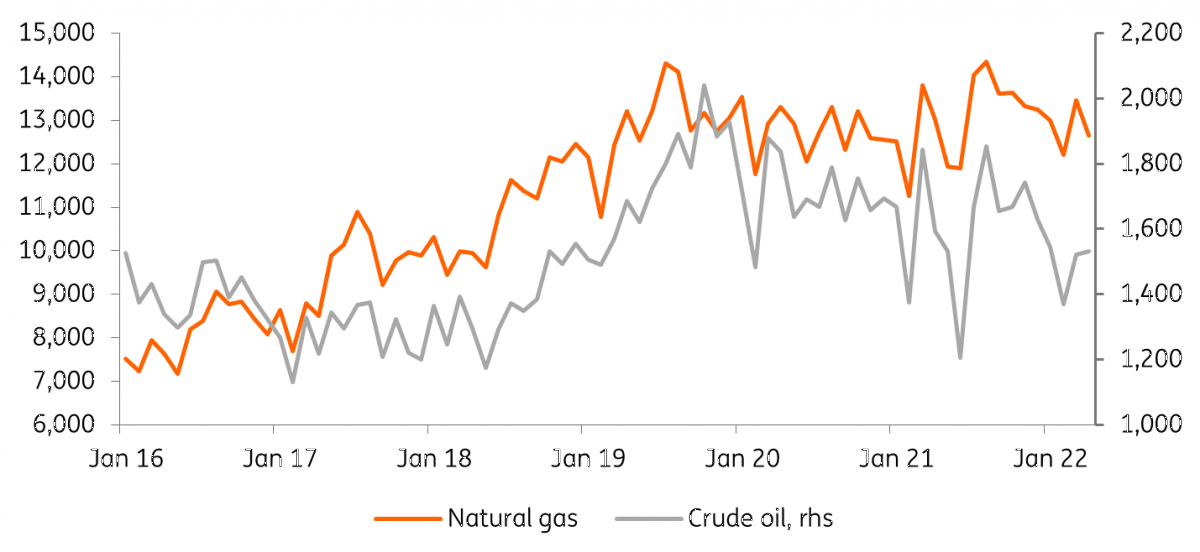

Australia's energy exports (million litres)

Australia's own energy crisis

Load swaps might have been another possibility, where Australia fills a gas order so another producer in the Northern Hemisphere can supply Europe.

However, all talk of Australia providing an answer to commodity supply shocks in Asia has evaporated, as, despite its substantial energy riches, Australia has been suffering its own energy crisis.

The crisis has been described as a "perfect storm", combining an early Australian cold snap, floods affecting coal production (65% of Australian electricity generation is from coal), and old unreliable coal-fired power generating capacity being offline. LNG exporters have been exporting as much gas as possible overseas, taking advantage of high global prices in the aftermath of supply disruptions to Europe of Russian gas.

Australian energy production (million litres)

The plan to fix the energy market

The crisis resulted in the suspension of the wholesale energy market for the East coast of Australia (including five of the six states). Capped electricity prices fell below what generators were having to pay to produce electricity – as expensive imports of coal and gas were required to make up for domestic shortfalls. The result led to some capacity being temporarily withdrawn raising the prospect of blackouts.

The response to the crisis has been an 11-point plan from energy ministers that includes the following:

- To develop a capacity mechanism, which would pay generating units to be available even if they are not used. This doesn’t explicitly rule out coal, but it is hoped will facilitate more renewables.

- Procure and store gas for situations of supply shortage.

- Move forward with a National Transition plan for growth in renewables, hydrogen and transmission.

Summary

Australia’s energy crisis is indirectly related to the spikes in energy commodity prices resulting from the Russia-Ukraine war. That, and an incoming government that appears to regard Australia’s energy transition as a more pressing concern than the outgoing government, could hasten the adoption of renewables, including green hydrogen, pumped hydro, and storage mechanisms including batteries, as well as their more efficient inclusion into the distribution grid.

However, the short-term may see more gas being diverted from exports to domestic use. It may also delay the phasing out of coal-powered generation while reliable alternatives are being developed.

The recent crisis, if nothing else, has highlighted the risks to Australia (and others) of energy supply disruption in an inadequately planned transition in the face of external shocks like that generated by the Russia-Ukraine war. The road ahead may look a little clearer, but a more deliberate approach to transition may mean that less progress is made in the short term even as targets for emissions reduction are strengthened.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

1 August 2022

How the Ukraine war has affected Asia’s race to net zero This bundle contains 9 Articles