A closer look at South Korea’s household debt problem

Korea’s high level of household debt has been regarded as a major risk factor for the economy for some time. We have taken a closer look at the issue and concluded that deleveraging with interest rate hikes would be painful and likely result in an economic downturn – but not an economic crisis

Korea's household debt

Korea’s high level of household debt has been regarded as a major risk factor for the economy for a considerable time. During the pandemic, household debt rose even more steeply thanks to accommodative macro policies. However, since August 2021, the Bank of Korea (BoK) has raised rates by a total of 200bp, and we expect it to raise at least another 50bp by year-end. In addition, fiscal policy is expected to normalise from next year. The basic theory in economics that tight monetary and fiscal conditions burden consumption and investment and cause financial deleveraging remains valid. Considering the highly indebted Korean household situation, we think that even at the expense of short-term growth slowdowns, orderly deleveraging is essential, which will do good for long-term growth.

So far, households have tolerated interest rate hikes and high inflation relatively well mainly on the back of the reopening of the economy, fiscal support, and improved income conditions, but a meaningful deterioration of consumption is expected from the end of this year. As the deleveraging of household debt is expected to accelerate from the current quarter, GDP growth is also likely to slow significantly. It is true that some aspects of household debt are riskier than others. A tight monetary policy will likely dampen private consumption eventually and trigger asset price adjustments in the short term.

However, we still believe that the systemic risks posed by household debt do not appear imminent. First, financial intermediaries and financial regulators have appropriate risk management systems in place; second, the Bank of Korea began to preemptively raise the policy rates last year; and lastly, policy assistance to alleviate the debt repayment burden is also planned. Let’s take a detailed look at household debt in Korea and examine the risks associated with it.

Household debt has remained very high and grown rapidly

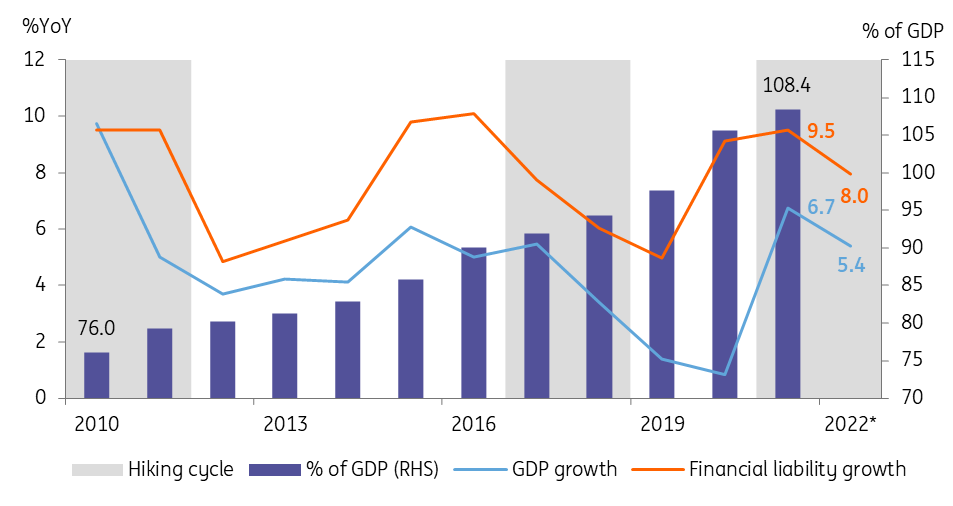

The financial liability of household and not-for-profit organisations has more than doubled over the past decade. According to the Bank of Korea, the amount of financial liability in 2021 increased by 9.5% year-on-year to KRW 2,245tr, exceeding the nominal GDP growth rate of 6.7% and reaching 108% of GDP. Looking at the composition of household credit, mortgage loans account for about 53% of the total, personal loans 41%, and merchandise credit 6% as of June 2022. Over the past few decades, the fastest and largest growing segment of household credit has been mortgages, primarily driven by rising real estate prices, while personal loans have also surged in the last couple of years, aided by easing monetary policy and increasing leveraged investment. On the other hand, merchandise credit, which includes credit card purchases for goods and services but excludes card loans and cash advances, grew at a pace similar to the nominal GDP growth.

Household debt remained very high and grew rapidly

Historical data shows that debt growth tends to decelerate during policy rate hikes and the latest data confirms that this negative correlation holds in the current hike cycle. We expect the negative correlation to strengthen even more in the coming months due to the faster pace of rate hikes this year compared to past hiking cycles.

Mortgages account for the largest amount of household credit, while personal loans are most sensitive to the rate changes

Mortgage loans account for more than half of total household credit

As of 2022 June, the total amount of mortgage loans stood at KRW 1,001.3tr, accounting for about 53% of total household credit. The level of mortgage debt is relatively high compared to other countries and the unique feature of the Korean rental system, Jeonse (about 64% of the house price for a two-year rental deposit, for more detailed information on Jeonse please click here), is a major contributing factor, in our view. Various sources confirmed that it is estimated that about 25% of the total mortgage loan is for Jeonse deposit and the rest is for the home purchase. The financial authorities have been encouraging banks to lend their Jeonse funds, judging that Jeonse contributes to the housing stability of middle and low-income households, so the number of Jeonse loans has grown steadily over the past few decades.

Korean house prices have risen in tandem with other major economies

It is not unique to Korea that house prices have risen rapidly in recent years. This has been a common phenomenon seen in other OECD countries such as the US, Europe, and Australia due to the accommodative monetary environment. In the case of Korea, the previous government’s policy to curb real estate prices is centred on suppressing housing demand. However, under such an abundant liquidity market environment, conflicting policy implementations stimulated demand for housing in certain areas (Metropolitan areas such as Seoul), resulting in a sharp rise in house prices.

The booming real estate market is a global phenomenon

To curb sharp rises in house prices, the government has tightened terms for mortgage loans more stringently since 2020. For home purchases, the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio in speculative overheated districts (basically, the entire area of Seoul) was lowered from 80% to 60%, and then again to 20-40%, and loans for a house value of KRW 1.5bn or more were not available at all. Eventually, with these stringent lending conditions at work, the growth of mortgage loans began to decelerate from last year, and this year the slowdown has been accelerating due to rapid rate hikes and growing concerns over valuations. As forward-looking data points to further price corrections, along with the continuing high-interest environment, mortgage loans will grow at a slower pace in our view.

Mortgages are expected to grow at a slower pace with a weak housing market outlook

Personal loans: the riskiest segment of household debt

Personal loans, the riskiest segment of household debt, amounted to KRW 756.6tr as of 2Q22, accounting for about 40% of the total. It grew rapidly during the pandemic as lending conditions eased and asset markets rallied. In addition, with mortgage loan requirements becoming stringent in 2019, it seems that the balloon effect of increasing personal credit loans has transpired. However, regulators put a cap on personal loan products soon after, so the total outstanding amount has declined for three consecutive quarters since 4Q21. We believe the downward trend will continue as COFIX, the widely used benchmark rate for personal loans, made the largest monthly gain in August, reflecting the BoK’s big rate hike in July. Also, unlike mortgage loans, early repayment fees are waived for most personal loans, and personal loans often have a maturity of less than one year, so there is more incentive for borrowers to repay their personal loans. As the number of personal loans tends to track asset prices such as real estate and equity, the recent weakness in KOSPI may limit personal loan growth as well.

Personal loans will likely continue to drop in the near future

The latest data support our view

Preliminary data from the Financial Services Commission (FSC) support our view. In July, household loans fell by KRW 1tr from the previous month. Mortgage loans increased by KRW 2.5tr mainly due to continued demand for group loans for new residential projects and Jeonse deposits. On the other hand, personal loans showed a sharp decline of KRW 3.6tr compared to the previous month as the repayment of loans increased due to the interest burden caused by the interest rate hikes.

Mobility data is a key leading indicator for credit card loans

Credit card debt has grown steadily over the long term, at a rate similar to nominal GDP growth. Credit card use has increased mostly through lump sum and instalment payments while cash advance has been continuously declining since 2003. In the first quarter of 2022, cash advances accounted for about 8.2% of the total card transaction amount while lump sum and instalment payments accounted for 71.5% and 20.4% respectively.

Over the past few years, credit card debt has fluctuated significantly in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic. Transactions dropped sharply in the early days of the pandemic due to strict mobility restrictions, but the gradual relaxation of those measures appears to have boosted credit card usage. Total credit card usage – including lump sum payments, install payments, and cash advances – has grown, on average, 11.4% YoY over the past 12 months (vs. avg -1.6% from March 2020 to February 2021) and is now back to pre-pandemic levels.

Credit card loans will likely rise for a couple of months

We expect credit card loans to increase in the near term as key leading indicators of household consumption, such as Google Mobility and Oxford’s Stringency Index, continue to improve. Although the high inflation rate, tightening monetary environment, and weak asset market will eventually put a burden on household consumption from the next quarter, we believe private consumption will remain relatively solid in the current quarter thanks to the strong jobs market and various government stimulus packages. In particular, healthy service consumption is expected to continue to benefit from the reopening effect for the time being.

What are the risk factors for household debt?

What is worrying about household credit is not the high level itself, but the fact that more than 80% of the outstanding loan balance is settled with floating rates, thus the debt service burden increases quite sharply if interest rates rise, which in turn can increase the default rate. More importantly, low-income groups will be particularly hard hit. According to the Annual Survey of Household Finances and Living Conditions, the most indebted income quintiles are fourth and fifth which are high-income groups, but in terms of the debt service burden, which is the ratio of debt repayments to annual regular income, it is much higher in the first quantile group (almost 50% as of 2020) than in the other groups, and the ratio will likely increase even more for this year and next. Although the total debt ratio of the first quintile is fairly limited, most of them are financially vulnerable, thus targeted policy support for orderly deleveraging is needed.

The debt service burden ratio for 1st income quantile is about 50%

For personal loans, the poor performance of asset markets could be a major risk factor due to the positive correlation between personal loan demand and asset market performance. New demand for leveraged investments will decrease, but it may be difficult to repay existing loans during a period of falling asset prices. But, we believe the bank’s stringent Debt-to-Service Ratio (DSR) standards will likely manage potential risks, to some degree. Unemployment and income conditions are the main two factors of loan delinquency and losses but these two factors remain healthy, thus the possibility of default is quite low. The unemployment rate for August stayed at 2.9% and is expected to remain below 3.5% by the end of this year. Real disposable income rose 8.3% YoY in 2Q22. Wage/salary and property incomes declined but transfer and business incomes increased sharply. We think wage/salary incomes will likely rise in the second half of this year as the majority of companies have not finished their annual wage negotiations with labour unions while the reopening will continue to support business income.

Household income conditions improved by the 2Q22, supported by government help

For mortgages, in theory, unless house prices plummet by more than 20%, the possibility of bad loans is still low because the financial authorities previously capped the LTV limit to 80% and recently lowered it to 20-40%. Home prices fell about 13% during the 1998 crisis but recovered quickly during the following expansion period. We don’t expect a nationwide sharp depreciation of house prices in the near future, but as the number of unsold properties outside the Seoul Metropolitan area is increasing, the price adjustment is expected to be steeper in small and medium-sized cities than in Seoul. Falling real estate prices will reduce the wealth effect, limiting household consumption activity. For the Jeonse deposit, as the Korea Housing Finance Corporation and other credit guarantee funds guarantee up to 80% of the Jeonse loan, the direct risk exposure for commercial banks is limited. But, for those who do not purchase Jeonse guarantee insurance, the sudden drop in the Jeonse price may be a risk factor.

House prices are expected to decline, particularly outside of Seoul

Although the current government has eased some loan terms for first-time buyers and personal loans from the beginning of the third quarter of 2022, it is unlikely that there will be immediate loan demand due to the fairly limited eligible groups and unfavourable market conditions for homebuyers.

The experience of transferring household debt to the financial crisis dates back to the credit card crisis of 2003 when credit card use was encouraged with the abolition of cash advance limits and the easing of card loan conditions, but risk management policies were insufficient. But, since then, there have been no such crises, even during the recession. Financial regulators have installed several risk management tools already, and financial institutions have developed better credit scoring and other risk monitoring systems.

Are there any signs of increasing default risks?

The non-performing loan ratio is a key indicator of potential signs of default risk. According to FSS data, the NPL of household loans at commercial banks decreased during the pandemic and reached a historically low level of 0.16%, and the big four commercial banks set up more than 200% of provisions as of 1Q2022. Thus, we think the household default risk remains low. However, if we look only at internet banks such as Kakao bank and K-Bank, NPL is on the rise and relatively higher than the average of banks. While the loan volumes from both internet banks are negligible, it could suggest that the overall delinquency ratio could rise over the coming months. Compared to other commercial banks, internet banks are considered riskier as their customers are concentrated in the medium-risk/medium-return and are younger in age. Therefore, it is worth keeping an eye on the NPL trends of these banks as the rate hikes have a more negative impact on risk groups.

NPL for household debt declines on average, but NPL for internet banks is on the rise

Bank's provisions are above 200% of NPL and the delinquency rate is still low and manageable

Policy will ease some of the burden on households and young people

In July, the government announced the refinancing policy fund of KRW 30tr, which incentivises households to refinance their existing mortgages from floating to fixed-rate loans at a high 3% level. This will mainly benefit middle and low-income households, targeting households with a house price of KRW 400m or less and a household income of KRW 70m or less. It also requires the repayment of principal thus also supports the deleveraging of household debt. This fund will take applications from 15 September.

As mentioned earlier, unprotected charters can be another risk factor for households and require policy support. Recently, some tenants did not receive their security deposits even after their leases were terminated. Accordingly, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport and related ministries announced a plan to prevent damage to Jeonse fraud. The offer includes providing emergency loans at an interest rate of 1% per annum and providing temporary housing to people who have not received their deposits back.

Meanwhile, the government will launch Youth Jump-up Account, which is a policy-type financial product that supports the youth to create an opportunity for asset formation, up to KRW 50m over five years. This is not a debt relief programme, but it is meaningful in that it provides incentives for youth savings so that they can be financially well-equipped.

Deleveraging will be painful but the economy can bear it

In this note, we have looked at the scale and breadth of household debt in order to better understand the current state of household debt in Korea. There are certainly a number of things to watch for and a few areas that are riskier than others. A faster pace of deleveraging combined with asset price corrections is expected and eventually private consumption, the main driver for this year's growth so far, is expected to contract in the near future. But, in our view, this is also part of the business cycle in which the economy normalises. More importantly, governments are proposing policies to prevent hard landings and support vulnerable groups, and the financial industry has already put in place rigorous monitoring and risk management tools. Therefore, the household credit crisis of 2003 is unlikely to be repeated in this economic cycle.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article