US: What to expect from the December FOMC meeting

The Federal Reserve will likely steer clear of more stimulus, but ramp up its dovish rhetoric and emphasise the need for more fiscal support as Covid-19 containment measures increasingly weigh on economic activity. Policy tweaking to limit the steepening of the yield curve is possible, but will probably be deferred until next year

Hope for the best, prepare for the worst

The medium-term economic outlook has undoubtedly brightened in the past few months with financial markets buoyed by favourable vaccine news while fears of a protracted and difficult Presidential transition have eased. Data flow has pointed to an ongoing recovery while hopes of another fiscal stimulus have recently been revived. This more positive backdrop helped the 10Y Treasury yield to touch 98bp last week, nearly double the 4 August low of 51bp.

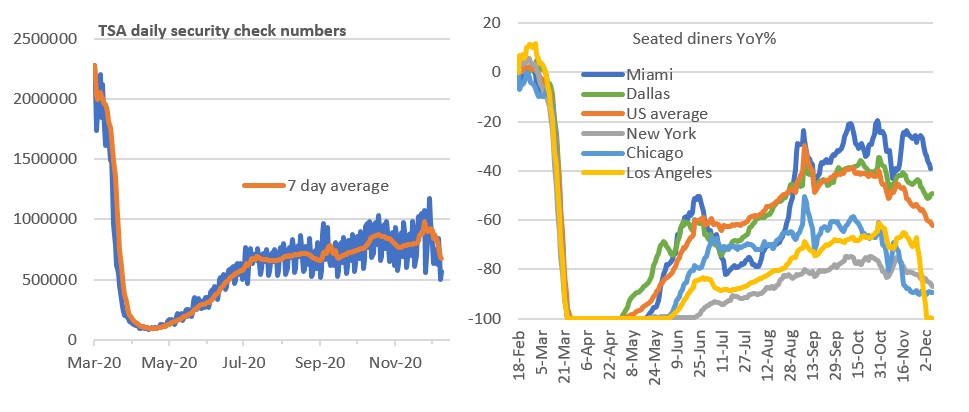

Yet, the US economy is not completely in the clear. While a vaccination programme is coming, it will take time before it is distributed to enough people to allow a full return to “normality”. In the meantime, Covid-19 cases are rising sharply and containment measures are being re-introduced at a heavy economic cost. This window of vulnerability could last perhaps three or four months during which restrictions on movement could push up unemployment and weaken activity.

Moreover, we have been talking for months about another fiscal stimulus to help tide the economy over before a full economic reopening. The latest comments from Senate Republicans suggest we shouldn’t hold our breath despite recent signs of movement.

Then there is the Treasury’s decision not to extend the emergency lending facilities, which clearly disappointed senior Fed officials who had a preference for keeping it as a backstop should conditions deteriorate.

Less movement & less spending = fewer jobs

Forcing the Fed’s hand?

The Federal Reserve believes fiscal policy is the best way to support the economy in the face of a second wave of the pandemic, but there is a school of thought that believes the Fed should do more themselves. This is a tricky situation though. With borrowing costs still close to record lows and credit markets functioning smoothly there is little they can seemingly do to boost the economy aside from emphasising they aren’t going to raise rates anytime soon.

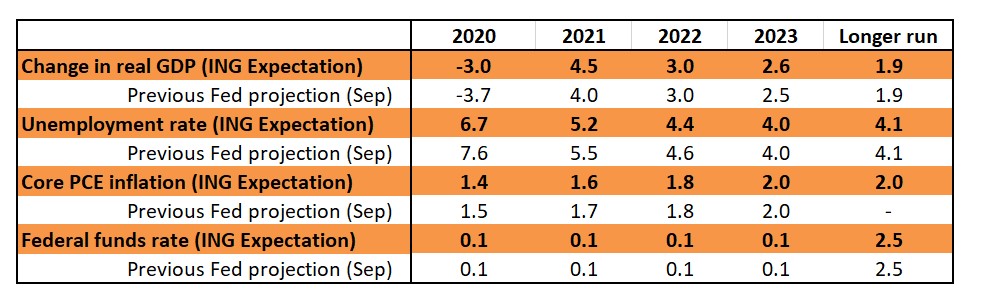

In this regard, the Fed will leave the Fed funds target rate at 0-0.25% next Wednesday, promising to keep it there until the goal of maximum employment and inflation being “on track to moderately exceed 2% for some time” is met – their “dot” diagram will continue to suggest this won’t happen before 2023.

We could see a change in guidance relating to the asset purchases, which currently stand at $80bn of Treasuries and $40bn of Mortgage Backed Securities each month. At present they merely comment that “over coming months” the purchases will continue “at least at the current pace”. Officials have hinted they could make the pace of purchases more conditional on economic conditions. They may also make the point that tapering of purchases must happen before they would even consider raising interest rates more forcefully. This may, at the margin, help to press down borrowing costs.

Capping yields a step too far right now

They could be more aggressive and seek to keep a lid on longer-dated Treasury yields, fearing that if the 10Y yield continues to rise it could constrain the recovery. Action could involve focusing a greater weighting of asset purchases at the longer end of the yield curve at the expense of fewer purchases at shorter durations.

We have our doubts that they will do that just yet though and will instead keep it in their toolbox for future use. The 10Y yield remains below 1%, which isn’t exactly threatening. We see it as more of a tool that could be used if there is a perception that Treasury yields are rising too far too quickly. That is more likely in an environment next year with a full economic reopening and the Fed being wary that rising borrowing costs threaten to unnecessarily impede the recovery.

After all, once a critical mass of people receive the inoculation, which we assume will happen during the second quarter, this can give consumers both the confidence and the freedom to fully re-engage with the economy. With savings levels having been replenished, there is a sense that consumer service sectors could experience something of a boom as people “make up for lost time”.

Business investment plans that have been put on hold for more than 12 months may quickly get put into action and if we then get another fiscal stimulus package on the order of 3-4% of GDP under President Biden, this could be a recipe for very vigorous growth from 2Q21 onwards. This is likely to be reflected in upward revisions to Fed forecasts.

Previous Fed forecasts & ING's expectations for new Fed predictions (%)

Inflation may also start to move onto the radar with vibrant demand coming up against supply constraints in many sectors – examples include numerous bars and restaurants that have permanently closed or airline fleets that have been cut back. In any case, there will be some upward pressure on annual inflation rates as the sharp price falls experienced during the height of the pandemic drop out of the annual comparison.

Following the BoC’s lead?

We suspect the yield curve will steepen further in this environment with 10Y benchmark government borrowing costs set to test 1.5% in 2021. Should it rise swiftly, the Fed may adopt the Bank of Canada’s strategy where it “recalibrated” its quantitative easing programme in October by shifting asset purchases towards the longer end of the yield curve while lowering the weekly purchases from “at least C$5bn” to “at least” C$4bn.

The BoC’s argument was that household and corporate borrowing costs tend to be more influenced by longer-term government borrowing costs, which is the same as in the US, so by focusing spending there they could achieve the same amount of stimulus using less ammunition. This is a neat way of starting to extricate themselves from the situation the BoC finds itself in and we suspect will eventually be replicated by the Federal Reserve – just not yet.

And there may or may not be some technical nuances discussed

The Federal Reserve may comment on the pushes and pulls likely on the money market in the coming months. Liquidity in the system will be affected by the spend of a chunk of the $1.5bn of reserves built by the Treasury and held at the Fed. This effectively gets injected into the system. And at the same time, T-bill issuance is set to fall, which means that this liquidity does not get mopped up easily. In consequence we could see some downward momentum in ultra-short money market rates.

The Fed won’t want to see this go too far, as they would like to keep the effective funds rate above the 0% floor (the last thing the Fed needs is for negative rates to become an implied point of discussion). To avert this, the Fed could increase the rate it pays on excess reserves, which would at least coax some excess liquidity into this avenue, reducing the downward pressure on the effective funds rate.

This would be a purely technical move, more likely in the first half of 2021. Bottom line, any talk of a rate hike here is purely for market adjustment purposes; nothing further should be read into it. In fact, the passage of a stimulus bill and chunk of extra T-bills issuance could take care of the issue without the need for a rate adjustment at all.

Download

Download article11 December 2020

Hard choices, hard Brexit, hard luck This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more