Russian budget consolidation may face obstacles in 2022

Thanks to high oil prices and cost control, Russia's budget will be in 0.4% GDP surplus in 2021 if oil stays at $75/bbl till year-end. For 2022, the government is guiding for further consolidation, driven by a 2.3% GDP cut in spending. This ambition will be challenged by the need to support household income amid faster inflation and slowing consumer lending

Budget to end 2021 in a 0.4% GDP surplus on high oil prices, one-off proceeds, and reduction in anti-crisis spending

In 9M21, the Russian federal budget was in a RUB1.4tr surplus, exceeding our RUB1.1tr expectations and touching the upper bound of the consensus range. This result was a combination of high commodity prices, strong 25% year-on-year growth in non-fuel revenues, and moderate 11% YoY increase in expenditures despite the recent pre-election spending splurge.

Given the strong 9M21 result, the recent improvement ING's near-term view on commodities markets and taking into account the Russian government's tradition of postponing a large chunk of annual non-social spending till the last month of the year, we now see the budget surplus continuing to expand to RUB2.0tr in 11M21 before narrowing to RUB0.5tr, or 0.4% GDP for the full year 2021. This represents a sizeable improvement of our previous expectations of a 0.5% GDP deficit for this year.

The expected surplus in 2021 will represent a material 4.3% GDP improvement in the budget position vs. the pandemic-ridden 2020

The expected surplus in 2021 will represent a material 4.3% GDP improvement in the budget position vs. the pandemic-ridden 2020 (Figure 1). More than half of that increase will be assured by a 2.3% GDP increase in the fuel revenues thanks to the increase in energy prices and recovery in volumes. Non-fuel revenues are likely to post a 0.6% GDP increase on recovery in economic activity, retraction of some anti-crisis tax exemptions and some one-off proceeds. Finally, expenditures will be cut by 1.4% of GDP from elevated levels of 2020, reflecting a gradual exit from the Covid response package initiated last year.

Adjusting the headline balance for the windfall fuel revenues (revenues received thanks to oil price exceeding the pre-determined base level, which according to the fiscal rule are to be saved in the sovereign fund) the federal balance will also show improvement vs. 2020, posting a 1.9% GDP, or RUB2.3tr, deficit in 2021. Earlier, the Finance Ministry indicated that around RUB0.9tr of that sum will be financed with the excess cash accumulated from the previous year, leaving the true borrowing requirement at RUB1.4tr for this year. This is smaller than the RUB1.8tr net borrowing guided by the Finance Ministry for this year, and the RUB1.7tr actual increase in the local public debt seen in 9M21. This means that the Finance Ministry has no real urgency to borrow at the moment and is probably doing so to assure a liquidity cushion for future periods. This excess cash could be used to lower next year's net borrowing needs (announced at RUB2.2tr for 2022) in case of adverse market conditions.

Figure 1: Fiscal consolidation in 2021 is helped by strong revenues and moderation of spending

Further aggressive consolidation is guided for 2022 due to expected drop in fuel and non-fuel revenues

Looking into the official budget proposal for 2022-24, which is due to be signed into the law by the end of this year, it appears that the Finance Ministry is looking to further tighten the stance in 2022-24, with a main bulk of adjustment prescribed for 2022. Next year, the government is looking to reduce the direct federal spending by 2.3% GDP to 17.7% of GDP, which is close to the levels seen before the 2020 stimulus (Figure 2). This is intended to lower the budget breakeven Urals price – the measure of the fiscal dependence on energy prices – from an elevated $68-74 range of 2020-21 to the targeted $53-58/bbl. The logic behind this is as follows:

- Due to the tradition of conservative fiscal planning, the government is assuming a gradual decline in the actual Urals price from $66/bbl this year to $62/bbl in 2022 and $56-58/bbl in 2023-24. Given those expectations, a decline in breakeven is required to avoid budget deficits in the coming 3 years.

- The government sees a decline in non-fuel revenues in 2022-24 after a presumably temporary spike in 2020-21. According to Minfin's projections, the completion of one-off transactions related to the Sberbank handover, penalties from the metals sector, and a number of other items, the non-fuel revenues are supposed to drop from 12.6-12.8% of GDP in 2020-21 to 11.4-11.6% GDP in 2022-24, which is close to levels seen before 2020.

- In order to somewhat offset the negative effect of declining direct spending, the government is discussing local investments into infrastructure out of the sovereign fund in the amount of US$12bn p.a. in 2022-24, which would represent additional support to the economy of around 0.6% of GDP.

Figure 2: Finance Ministry expects a sharp reduction in fiscal spending in 2022 to address elevated breakeven

Consolidated spending to be reduced by 3.0% GDP, limiting direct support to household income

The enlarged budget system, with includes federal budget, regional budget, as well as State Pension Fund (PFR) and Social Security Fund (FSS), is also expected to cut overall spending in the next 3 years. In 2022, the consolidated spending is expected to be cut by 3.0% of GDP to 35.5% GDP, close to the levels seen during 2015-17. This 3.0% cut is to be assured by the above-mentioned 2.3% cut in the federal spending (out of which 1.2% reflects a decline in the federal support to the regional budgets and social funds), while the rest is the cut in the own spending by the regions and social funds.

When discussing general budget policy and its implications it is important to look beyond the headline federal parameters. On the one hand, regional budgets and social funds have limited independence, as very few regions have the ability to finance their deficits on the market and the social funds are entirely dependent on the federal support. But on the other hand, the main bulk of direct support to the household income, including salaries to state employees in education, healthcare, pensions and other social payments (accounting for around 60% of the consolidated spending) are administered outside the federal budget.

According to our estimates based on the budget proposals, the government is looking to reduce the direct support to household income from 21.3% GDP in 2021 to 19.6% GDP in 2022, bringing it back to levels seen prior to 2020 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Tightening consolidated spending will lead to reduced direct support to household income

The government directly supports 42% of population and 34% of the household income

We see several reasons why the proposed rollback of state expenditures, including on social payments and other forms of direct support to household income, could be challenged by economic reality.

- First, it is important to keep in mind, that pensioners and employees in the public sector, including teachers, doctors, state officials, the military, and the police represent 42% of the population, and their earnings account for 34% of the overall annual household income, as of 2021, according to our calculations (Figure 4). Over the last 10-15 years the dependence of the population on the direct state support has been gradually increasing. The social obligations of the Russian budget are difficult to reverse.

Figure 4: State spending cut would be a challenge to household income, which is highly dependent on state support

Each extra 1 percentage point of inflation increases state spending on household income by up to 0.2% of GDP

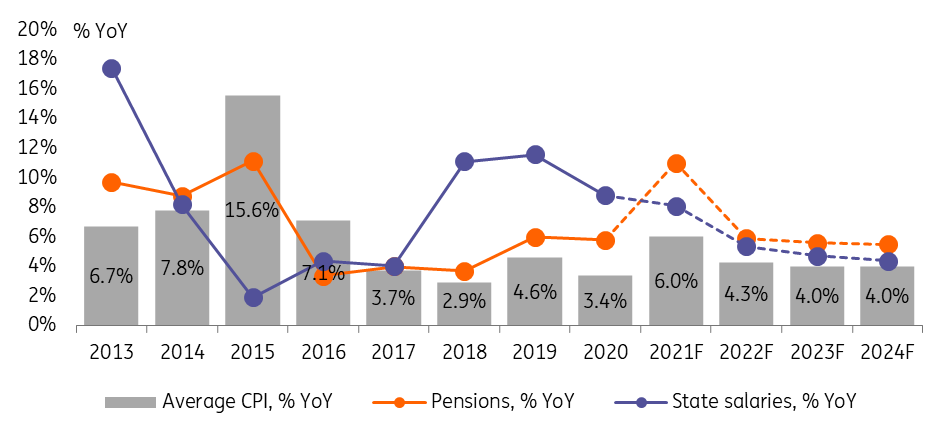

- Second, state spending on household income, particularly pensions, is subject to mandatory upward revision (indexation) depending on inflation, as confirmed this week by the president. The public sector salaries have no legal link to inflation, but the historical experience suggests that the link exists in practice (Figure 5). In the last 10 years, there were only two years (post-crisis 2015-16), when nominal pensions and public salaries lagged behind the average inflation, and that episode prompted a catch-up in 2018-20.

The current official spending projections for 2022 are based on the assumption of 5.8% CPI growth at year-end 2021 and 4.0% CPI increase at year-end 2022 (corresponding to 6.0% and 4.3% average annual CPI for 2021 and 2022, respectively), which now looks too optimistic. The Ministry of Economic Development has just increased the year-end CPI target for 2021 to 7.4% (corresponding to 6.4% annual average), while keeping 2022 unchanged so far. We would not exclude the need to raise the 2022 average CPI expectations to 5.7%, which may have implications for the state spending.

According to our estimates, each 1 percentage point of inflation boosts pension spending by RUB100bn, other social spending by RUB50bn, and public salary spending by RUB100bn, meaning up to 0.2% of GDP of extra spending. Assuming the actual CPI in 2021-22 exceeds the initial government expectations by 1.8 percentage points, the budget is facing extra spending of RUB450bn, or 0.3-0.4% of GDP in 2021.

Figure 5: Household income support will require an upgrade if CPI exceeds optimistic expectations

Official household income growth expectations could prove too optimistic

- Third, even without the inflation surprise, more state support might be required in order to fulfill official expectations of real disposable income growth in 2022-24. According to the current projections by the government, Russia is to see a 3.0% increase in the real disposable income in 2021 and 2.4-2.5% p.a. increase in 2022-24.

The 2021 target is easily achievable thanks to the low base of 2020, rapid recovery in employment, and the active participation of the state in the household income (Figure 6). For example, 1.9 percentage points out of expected 3.0% real disposable income growth in 2021 will be assured by the state, according to our estimates. However, the budget draft for 2022-24, in our view, suggests that in 2022 onwards the real disposable income growth is to be assured entirely by the private sector, which we find too optimistic. According to our calculations, the pre-crisis 2013 was the last year when the private sector managed to make a positive contribution to the household income growth in Russia.

Figure 6: Government expects 2022 real disposable income growth to rely entirely on the private sector

Household income growth in crucial to assure consumption growth

Russia's ability to show household income growth is crucial for its growth story, as other sources of financing consumption, such as leverage and savings, are becoming less reliable:

- Following a rapid growth in retail lending, which the Bank of Russia expects at 18-22% this year, including 20-24% for mortgages, the household debt burden will have reached 20% of GDP, including 11% of GDP in the unsecured consumer lending segment, a historical high for Russia and a cause of concern for the regulator, which is tightening the macro prudential framework to cool down this segment. At the same time, Russians' savings rate is looking to drop to historical lows (Figure 7), suggesting the need to replenish the cushion in the following years.

- While the retail lending growth is expected to see a cool down in the coming years, households are facing the need to service the growing interest payments on the previously accumulated debt (Figure 8), limiting the potential net support of retail lending to consumption after 2021 (Figure 9).

- The gradual reopening of borders should narrow the extra funds available for local consumption, which totaled 1.8-2.0% of GDP in 2020-21.

Without a reliable source of household income, the Russian growth story may become increasingly dependent on the export recovery, which is subject to long-term uncertainties because of the energy transition.

Figure 7: Consumer lending is at historical highs, savings rate at minimum

Figure 8: In 2022, retail lending growth to slow down, while interest expense will catch up

Figure 9: Retail lending is unlikely to support household consumption in 2022

In our view, the government's ambition for sharp budget consolidation in 2022 are based on optimistic assumptions regarding inflation and household income. Given the previous track record, we take expectations of strong recovery in the private sector income as optimistic and believe that above-expected support to pensioners and state sector employees is unlikely to be avoided. As a result, we do not see a decline in the budget breakeven Urals below $60-65/bbl in the coming years, around $10/bbl higher than assumed in the official budget projections. In the absence of structural measures and little scope for monetary easing, the government will be tempted to use the fiscal resources as a tool to preserve the current growth model.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more