Bank of England and Treasury announce temporary monetary financing

The agreement between the Bank of England and UK Treasury to give the latter access to a larger overdraft will rekindle the debate over direct monetary financing. But assuming the overdraft proves to be a temporary stop-gap, as it was in 2008/9, then it should help money market functioning. We don't expect it to be particularly negative for sterling

The 'Ways and Means' account

The Bank of England and the Treasury agreed on Thursday to expand the government’s overdraft facility – officially known as the ‘Ways and Means’ facility – with a stated goal of allowing the government to smooth its cash flow.

Against the backdrop of rising national deficits globally, this story will undoubtedly help rekindle the discussion over direct monetary financing as a tool to deal with all the extra government spending related to Covid-19. And it follows a string of proposals, not least from former Deputy Governor Charlie Bean, to move towards funding the government more directly, for example by buying bonds in the primary market.

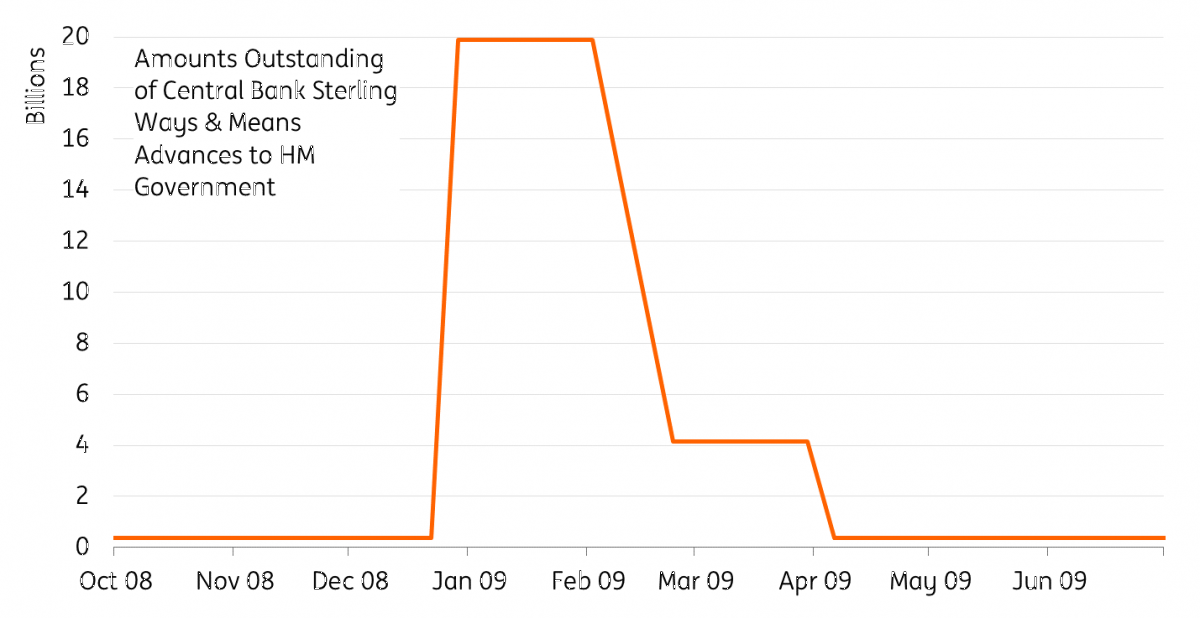

Before getting ahead of ourselves though, it is important to remember this overdraft facility isn’t new – and has been used before. Back in 2008, there was a similar agreement and the Treasury drew £20 billion from the Bank of England facility, for a period of around six weeks, according to official data. In normal times, this facility usually totals around £400 million.

In the end, everything depends on whether the usage of this facility is temporary. And assuming it is, we think it should help money market functioning, in so much as it should prevent the market from choking on Gilts (more on that below). Investors will assume that whatever is borrowed from the BoE will be refinanced on capital markets.

The bigger question for the 'is it/isn't it' direct monetary financing debate, will be how the Bank of England gets involved when the Treasury does refinance any overdraft position. Further QE is likely if needed to contain rises in market rates, but will policymakers resort to more direct forms of financing as some have proposed? For the moment, the Bank is keen to make clear it's independence means such policies are not on the cards.

How the 'Ways and Means' account was used in 2008/9

Will the temporary become permanent? Unlikely…

From the point of view of sterling rates, the reinstatement of the facility raises two questions: is it credible that it will indeed be a temporary cash management tool, and how this will later impact money markets and long-dated interest rates?

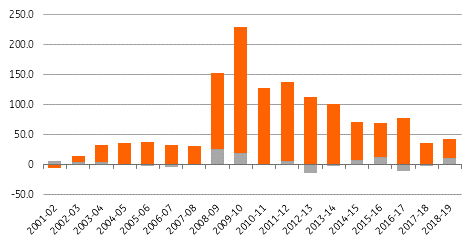

On the first question, it seems sensible to compare deficit forecasts to the Debt Management Office’s (DMO) borrowing capacity. We appreciate this is very early in the crisis and any estimate is liable to be revised higher if the economic disruption lingers but we use the Institute of Fiscal Studies’ £175bn forecast as a starting point. Whilst that figure seems impressive at first, the DMO managed to raise £150bn in fiscal 2008-09, followed by an additional £230bn the following year. This was at a time nominal GDP was lower than currently, and the BoE has already announced a £200bn boost to QE.

If HM Treasury’s drawdown of the facility remains in the same ballpark as historical usage, around £20bn, we can safely say that it has the capacity to refinance it with regular bills and Gilts issuance in subsequent weeks and months. Even larger amounts would make sense as long as it is clear they are temporary. Given the speed at which economic hardship is hitting the private sector, it is conceivable that even the DMO does not have the ability to raise these sums on time however. For instance, since 2001, the greatest one month Gilt net issuance it achieved was £28bn.

Total bill and Gilt net issuance per fiscal year

A relief to money markets and Gilts

This brings us to the second question about the impact on the functioning of GBP money markets (MM) and long-dated rates. At a time central banks are scrambling to restore the functioning of MM, for instance with the commercial paper facility, a sudden increase in the amount of debt instruments would be counterproductive: think of additional bill issuance as mopping up the liquidity the BoE is trying to add to the system, and crowding out corporates funding. In that sense, the introduction of the facility is a positive development and we would even recommend that it is used aggressively at first to prevent a disruption to money markets.

Where longer-dated rates are concerned, aggressive use of the facility would also prevent the market from choking on Gilts. Clearly investors are going to assume that whatever is borrowed from the BoE will be refinanced on capital markets but it will be reassuring to them that not all of it is issued at once. What’s more, it is hard to imagine the central bank will let a sharp rise in interest rates occur at a time when both private and public debt are on an explosive trajectory. Gilts trade with a strong BoE put embedded in them implying further purchases would materialise if necessary.

GBP impact unlikely to be overly negative, given BoE may be an outlier in form, but not in essence

We don’t see today's announcements as overly negative for GBP. This is because:

- In these uncertain times, what would normally be deemed as aggressive measures are being forgiven by markets and given the benefit of the doubt. Recall the limited GBP reaction to the large UK fiscal stimulus announced in March, as well as the subsequent rating outlook downgrade. What matters at this point is the impact on the economy and stability of financial markets. We view Thursday´s announcement through the lens of the financial stability prism, which should be positive for Gilts (see above) and not negative for FX.

- The BoE enjoys a high degree of credibility. This is important as it is necessary for the markets to believe that today´s announcement is a short-term, time-limited, extraordinary measure which won't last beyond 2020. This, in turn, should keep any negative effect on GBP fairly limited.

- While the BoE is the first major central bank to talk about/allow for what may be described by some as direct monetary financing, one can argue similar things are happening elsewhere, albeit indirectly. The increase in size/roll out of QE among central banks globally (be it in developed or emerging markets) with a partial aim to alleviate pressure on the domestic bond markets (due to the increase in bond issuance) provides a case in point. Here, the BoE may be an outlier in form (financing the government directly), but not necessary an outlier in essence (containing government borrowing costs).

We therefore don’t look for a material negative effect on GBP and don’t see the need to change our forecasts on the currency with a more negative outlook. We continue to target the EUR/GBP 0.85 level by the year-end.

Download

Download article9 April 2020

Covid-19: The global battle continues This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more