Asian foreign exchange in tariff tantrum

The near-term outlook for Asian currencies is unambiguously negative – further out, the scope for some recovery remains

Trade war is upon us

It seems as if we've been talking about trade wars for months now yet until this week, no tariffs had actually been levied, and some still hold out hope that a trade war can be averted.

We think it's getting too late for that. We sense that the Trump administration feels the global trade environment is unfair, that tariffs can help redress the balance in the US’ favour and that it can win a trade war. We disagree with both the premise and the solution - but that doesn’t change anything. Tariffs are coming, and some have already arrived.

With tariffs we expect global trade growth to worsen. This is going to be important in terms of local Asian currency (FX) strength, but exactly how much and for how long is a more complicated story.

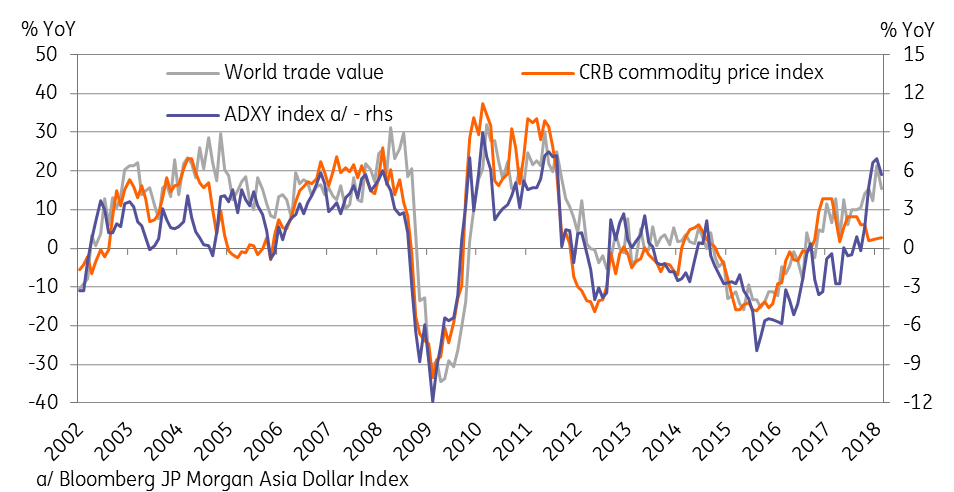

Let’s start by considering the relationship between global trade and Asian currency strength. The figure below shows world trade in USD plotted against both the ADXY index (index of nominal Asia ex-Japan currencies) and the headline CRB commodity index.

World Trade, Commodity Prices and Asian Currencies

The measure of global trade we have used is from Bloomberg, which derives it from IMF data. Trade is calculated from imports, not exports, as these are viewed as the least distorted of the two series. In contrast to the Dutch Trade statistics, which are sometimes used, this data is more timely and is available more frequently, making for easier comparison with real-time indicators like foreign exchange.

What strikes us particularly, is that while so many of the relationships that held before the global financial crisis have either weakened or been utterly destroyed, the relationships shown in the figure above holds firm before, during and after the global financial crisis.

We believe the trade environment for Asia will continue to deteriorate through the rest of 2018. But there is a chance that the outlook after that will be less threatening

Given that Asia accounts for about a third of all global trade, Europe for about 40% and North America, only about 10% and the logic of this becomes hard to refute. A negative shock to global trade will hurt the growth potential of one of the most trade focussed regions in the world. Moreover, relative to GDP, trade is even more important for Asian growth despite accounting for a slightly smaller share of the world trade total than Europe. Hit this trade outlook with a negative shock like tariffs, and local Asian currencies are going to suffer.

So what are we really looking at in terms of the trade outlook? In the short term, the prognosis isn’t good. Tariffs, retaliatory tariffs, and retaliation to that retaliation describes the situation between the US and China so far. But globally, the picture is even worse. The US/EU trade theatre of war is almost as ugly as the US/China campaign, and let’s not get started on NAFTA.

So as a risk scenario, we are considering a temporary 20% decline in global dollar trade values. That is not as big a drop as during the global financial crisis. But it could still result in a decline of the Asian FX index of about 6%-7%.

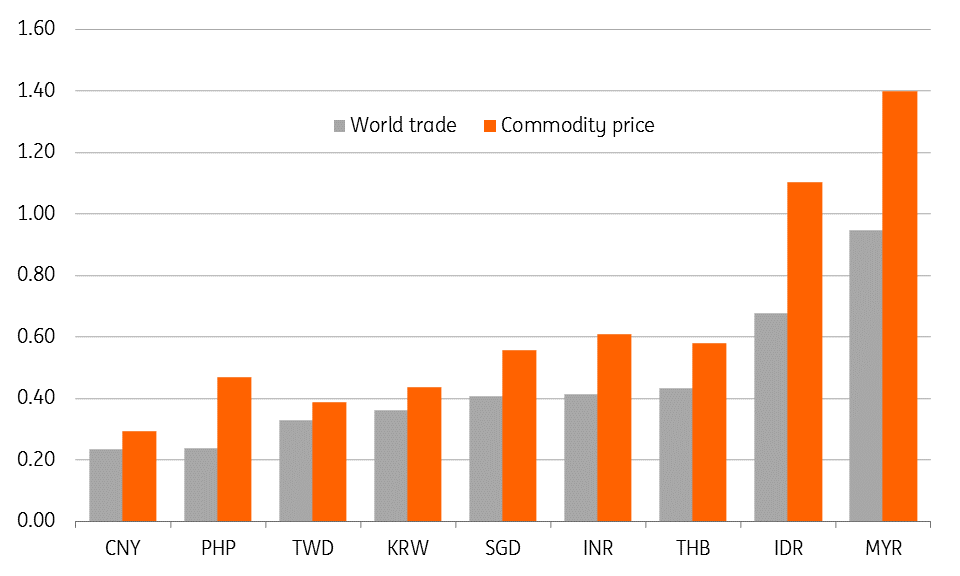

Currency sensitivity to trade and commodity prices

But the story doesn’t end there, because a fall in global trade of this magnitude is likely to weigh on commodity prices. China is the word’s marginal consumer of most commodities, so anything which hurts China’s purchasing power is also likely to weigh on commodities, and this could be the second leg of a looming global trade shock.

The figure below presents elasticities of each of Asia ex-Japan currencies to both trade and commodity prices derived from the simple regression analysis.

Asian currency elasticity to world trade and commodity prices

The Chinese yuan is the least sensitive of all currencies, but then it is not a free float, so that isn’t too surprising. At the other end of the spectrum is the Malaysian ringgit (MYR) and the Indonesian rupiah (IDR). These currencies are much more sensitive to commodity prices.

The impact of a trade shock will also vary depending on the hit to individual economies via their external payments situations. That is to say that currencies of countries with trade and current account deficits – India, Indonesia, and the Philippines - will be more vulnerable than those of surplus countries like – Thailand, Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Singapore.

The level of economic openness and currency management system are other determinants of the magnitude of any shock on individual economies. Less open economies or those with heavily managed currencies should be less vulnerable to external trade shocks.

CNY takes the brunt of the impact

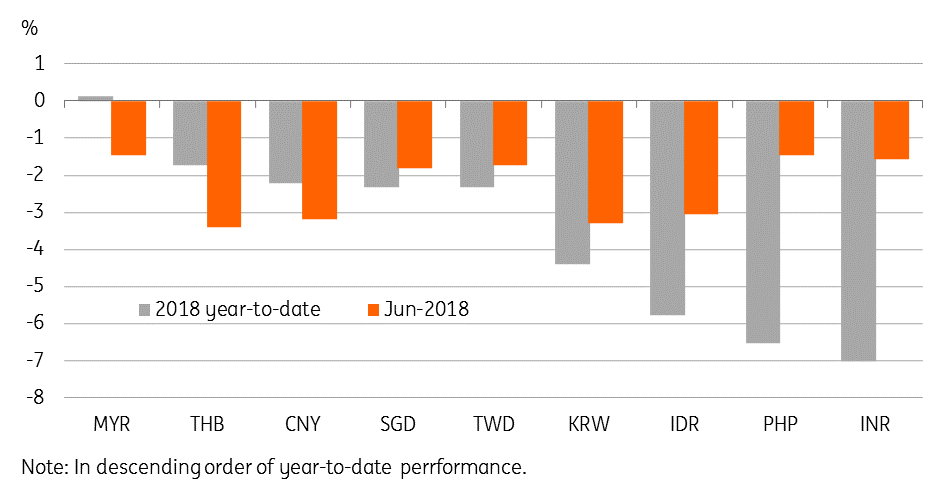

In contrast to the analysis above, President Trump’s announcement of $50bn tariff plan on 16 June has swung the fortunes of the Chinese yuan (CNY). This has swung from being Asia’s most resilient currency earlier in the year to one of the worst performers in the recent sell-off. Over 3% CNY depreciation against the USD since the beginning of June is reminiscent of the devaluation in August 2015.

Asia ex-Japan currency performance year-to-date

This raises the question of whether a weaker currency could be one of China’s weapons in the current trade war. Our Greater China Economist, Iris Pang, doesn’t think so.

Some of the other biggest underperformers in the region in the most recent sell-off are neither current account deficit countries, nor commodity producers, but instead, are heavily engaged in technology, for example, the Korean won. For them, the recent currency weakness is partly a reflection of tech stock anxiety, and the US sanctions on ZTE have no doubt played a part. Though in time, a technology embargo by the US on Chinese producers simply plays into the hands of the likes of Korea and Taiwan, who can pick up that market share. What we are seeing is merely short-run disruption.

Moreover, what we are seeing with the Korean won could also simply reflect that it is one of the bigger more liquid currencies in the region. When foreign investors pull out of Asian FX, they probably have bigger exposures to Korea than many other currencies. That is what they sell first, even though on most fundamental grounds, Korea is one of the most attractive investment propositions in the region.

Though further weakness cannot be ruled out, we sense that the following phases of Asian FX weakness will be kinder to the tech-heavy currencies than either the commodity-producing economies including the Indonesian rupiah and the Malaysian ringgit or the current account deficit countries such as the Indian rupee, Philippine peso and the Indonesian rupiah.

Indeed, the recent aggressive rate increases from Bank Indonesia seem to show a degree of prescience, as they appear on both of our ‘at risk’ watch lists. Central bank action can offset what is coming, but at the expense of domestic demand, and will be more effective combined with a reining back of some of the fiscal expansion that has played a large part in creating the external imbalances in these economies (that doesn’t look likely anywhere).

Recession or not?

As argued so far, the direction for Asian FX is clear, but the timing and extent of the weakness for individual currencies is less certain and subject to many more moving parts than would be ideal.

A valid question linked to this debate is whether this could be the source of the next global, or at least Asian recession - a theorem that has begun to attract some vocal followers in recent weeks. In our view, it is certainly possible. Though some factors provide a little comfort.

We’re currently dealing mainly with protectionism, not weak global demand. Though of course, the former could well lead to the latter. Moreover, at the moment, the situation is best described as the US against the rest of the world, not a multilateral trade conflict. It is possible to imagine a proliferation of trade deals between the rest of the world in this environment, but which exclude the US (for example the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership - RCEP), which might even deliver a global net trade boost - a sort of “My enemy’s trade enemy is my friend” situation.

A financial crisis was at the root of the 2008-09 recession, - with contagion from the US to the global financial system. That’s not the case today. Though there is growing concern about a possible Chinese credit crunch. So far, this is contained.

Tighter monetary policies before the 2008-09 crisis, subsequent regulatory clamp down and fiscal austerity made a bad situation worse. Monetary policies are still relatively loose today in both emerging and developed countries, despite some withdrawal of accommodation by the Federal Reserve since last year. Fiscal policies are not particularly loose except in the US and don’t look likely to be reversed imminently.

The domestic-demand-driven growth in most Asian economies could cushion some of any negative trade impact, though how long this would hold out if the trade sectors begin to crumble is debatable.

In short, there are some mitigating factors, but none are hugely comforting. A worst-case scenario might not be as bad as the global financial crisis, but it might still be pretty bad.

Expect a moderately negative trade impact

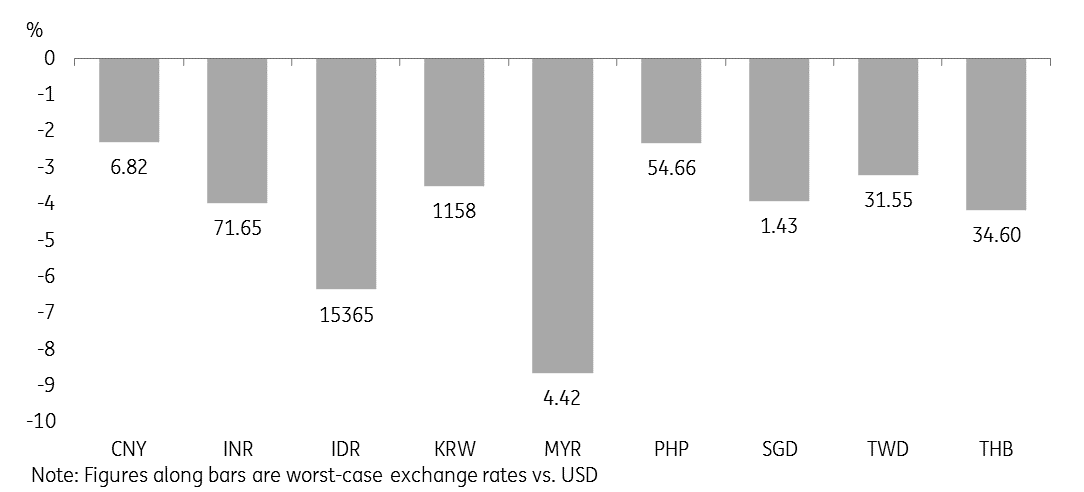

We believe the trade environment for Asia will continue to deteriorate through the rest of 2018. But there is a chance that the outlook after that will be less threatening. In our worst-case scenario, global trade falls by only about 10-to-20% (similar to that witnessed during the 2014-15 oil slump – and about half that during the global financial crisis). Subject to the caveats of our earlier analysis, that implies a 2-8% downside risk for regional currencies.

Impact on Asian currencies of 10% fall in world trade

Some hope

We believe the US public is the main intended audience of recent US trade policy actions. It doesn't appear to be US business, who on the whole, take an orthodox view of the benefits of trade, no doubt knowing first-hand the benefits that trade brings.

This motivation is likely to run strong ahead of the US mid-term elections. But if Republicans come out of the mid-terms poorly, and there is a chance that they lose the House of Representatives, then they may be less willing to support the President’s protectionist leanings.

Though, this has to be viewed against the possibility that the forthcoming nomination to the Supreme Court may help Trump rebut any attempt by a less friendly Congress to overturn some of his recent security based trade policies as unconstitutional. As stated – this stuff isn’t simple.

Along with political developments, the outlook for the USD, in major FX pairs, and by extension for Asian FX, will also be determined by the pace and degree to which the European Central Bank moves towards removing its negative deposit rates. That, in turn, will also be influenced by the global trade outlook.

In short, there are too many moving parts to this story to do anything more than highlight the scenarios. But what is clear, the outlook for Asian FX is negative, and we have shifted our near-term forecasts accordingly. The latest Asian FX TalkING details the recent steps taken in this direction. But a continuous negative watch on our current Asian currency forecasts remains the order of the day.

Download

Download article6 July 2018

In case you missed it: Trading blows This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more